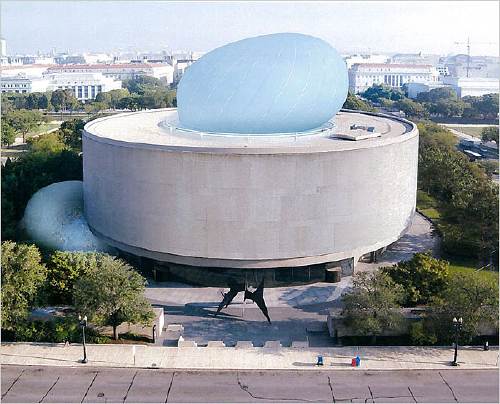

I’ve had a research question simmering on the back burner for a while, trying to figure out what the history of modernism and contemporary art have been in Washington DC. Partly, it was the dearth of good modernist architecture that got me wondering, then a crash course in the history of contemporary art and official Washington generally, and the odd genesis of the Hirshhorn Museum specifically. Then there was some sporadic attempts at securing Washington’s place at the art world table [more on those later].

Then last spring, I attended a dinner in the State Department’s Diplomatic Reception Rooms. Though they were originally built in an off-the-shelf, 1950s corporate modernist style that matched the building, in 1969, Walter Annenberg, Richard Nixon’s newly appointed ambassador to Great Britain, gutted the space and installed the current veneer of neo-colonial splendor. That gut job stood in nicely for the essentially anti-modernist hostility of the Washington Establishment. Little did I know.

In the the latest batch of White House documents released by the National Archives and the Nixon Library this week is an incredible 1970 memo from Nixon to his chief of staff H.R. “Bob” Haldeman, outlining a direct, political assault on the NEA’s support of “the modern art and music kick,” which he he associated with “the Kennedy-Shriver crowd,” art whose supporters “are 95 percent against us anyway.”

The LA Times’ Christopher Knight has some great context and quotes, but the full document is well worth a read [pdf]. My favorite part is the postscript, which has Annenberg’s fingerprints all over it:

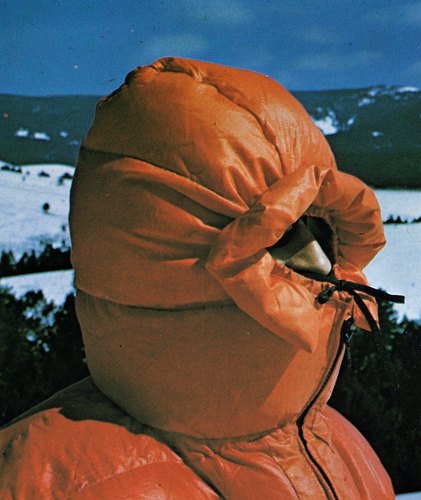

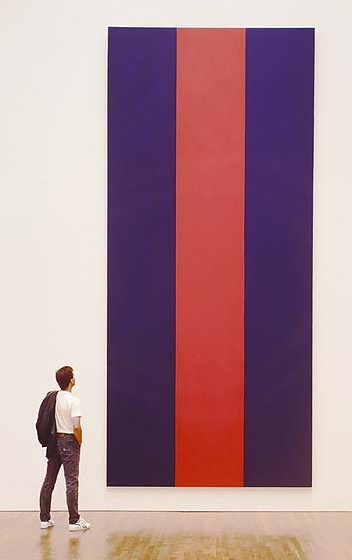

P.S. I also also want a check made with regard to the incredibly atrocious modern art that has been scattered around the embassies around the world…I know that [Kenneth] Keating has done some cleaning out of the Embassy in New Delhi, but I want to know what they are doing in some of the other places One of the worst, incidentally, was [career Foreign Service Officer Richard H.] Davis in Rumania.

We, of course, cannot tell the Ambassadors what kind of art they personally can have, but I found in travelling around the world that many of our Ambassadors were displaying the moder art due to the fact that they were compelled to because of some committee which once was headed up by Mrs. Kefauver and where they were loaned some of these little uglies from the Museum of Modern Art in New York. At least, I want a quiet check made–not one that is going to hit the newspapers and stir up all the troops–but I simply want it understood that this Administration is going to turn away from the policy of forcing our embassies abroad or those who receive assistance from the United States at home to move in the direction of off-beat art, music, and literature.

The “little uglies” probably came from MoMA’s International Council, which, along with the DC-based Woodward Foundation, often arranged embassy art loans.

Until the creation of the committee Nixon referred to, that is. The Art in Embassies Program was started in 1964 by Nancy Kefauver, who was selected by John and Jackie Kennedy for the post. In a 1990 NY Times history of the AIEP, David Scott, who helped Kefauver get going, recalled that Washington was scorning modernism just fine before Nixon took over:

“It was at a time when we were still fighting the battle of whether modern art was seditious or evil or un-American…As a result of the McCarthy period, people were very suspicious about having any government agency deal with abstract art. If you didn’t like the art, maybe the person was a Communist.”

Digging around, I’m kind of intrigued by Michael Krenn’s 2005 book Fall-out shelters for the human spirit: American art and the Cold War, which looks at the US Government’s interactions with the private art world, primarily through the State Dept, the USIA, and the Smithsonian. From the preview:

What the government hoped to accomplish and what the art community had I mind, however, were often at odds. Intense domestic controversies resulted, particularly surrounding the promotion of modern or abstract expressionist art. Ultimately, the exhibition of American art overseas was one of the most controversial Cold War initiatives undertaken by the United States.

At $50, though, I might need a little more than a Google Book preview.

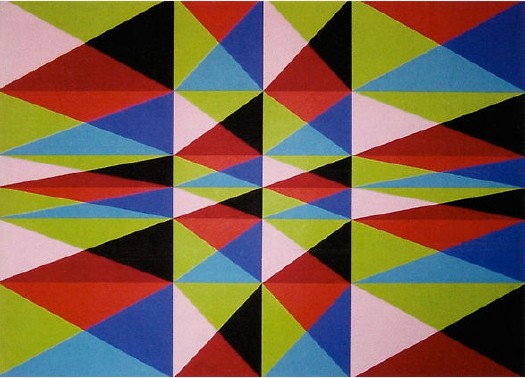

Meanwhile, poking around MoMA’s archive site to try and see what some of these ‘little uglies’ might have been, I found the 1966 exhibition, “Two Decades of American Painting 1945-1965,” organized by Waldo Rasmussen, which included 111 works by 35 postwar artists, including Gene Davis, Hans Hoffman and Jasper Johns.

It was a straight-up museum exhibit, not embassy art, but it did travel to India and Australia from Japan, and was accompanied by a film program, The Experimental Film in America, which sounds specifically designed to give Nixon an aneurysm.

And the Johns that was in the show? the a White Flag painting from 1955, which the artist held onto until 1998, when he sold it to the Metropolitan Museum.