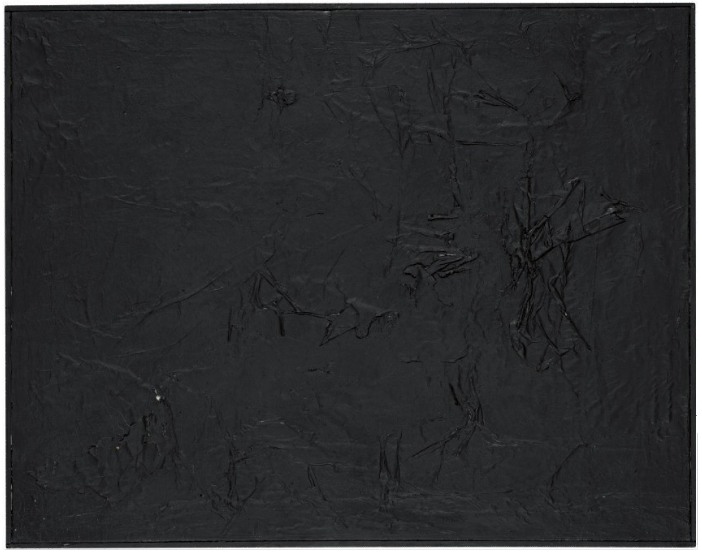

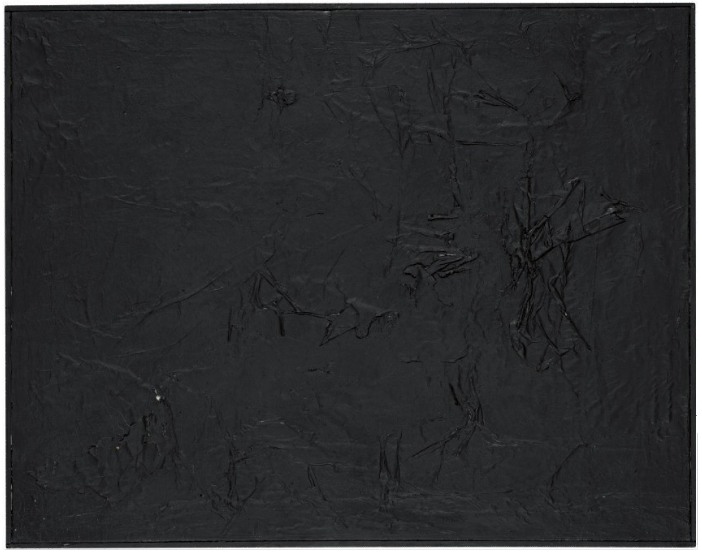

I took the kid to see Merce Cunningham Dance Company’s Legacy Tour the other night. And as I’m reading up on the funding of the Trust that will oversee Merce’s choreography after the company disbands, I found a mention of Robert Rauschenberg’s No. 1, a 1951 black painting which was sold after Merce’s death in 2009. Fascinating and, as I look at Bob’s unusual collaborative combine from a few years later, newly complex.

No. 1 was a gift to John Cage, which sounds simpler than it was. Cage had seen Rauschenberg’s first one-man show at Betty Parson’s Gallery in May 1951, and had asked for a work. As Christie’s catalogue entry put it, “The price, he said, was unimportant as he couldn’t pay anything. It was in this way and in this form that this painting first entered Cage’s possession.” As Carol Vogel put it in writing about the auction, Rauschenberg didn’t give the painting to Cage until “some years later.” But that can’t be right, as we’ll see below.

What No. 1 looked like at that point, no one is able to recall. Whatever it was, Rauschenberg had actually painted it onto a painting by his wife, Susan Weil. Vogel notes that Weil’s signature, and the date, 1951, are on the back of the painting, as is Rauschenberg’s. [Christie’s catalogue description only mentions the latter.]

This may have been an economic move as much as, if not more than, a collaborative or negating one. At the time, Rauschenberg and Weil were broke, using cheap blueprint paper to make photograms in the bathtub of their basement apartment on the Upper West Side. Here’s his recollection of the situation from his 1976 Smithsonian catalogue:

This period was exciting and prolific even if quality was erratic. We were both doing a minimum of five works a day. Clyfford Still came to the house to select a show with Betty Parsons. I was so naive and excited that by the time of the opening several months later, the selected show had been painted over dozens of times, and was a completely different concept. Betty was surprised.

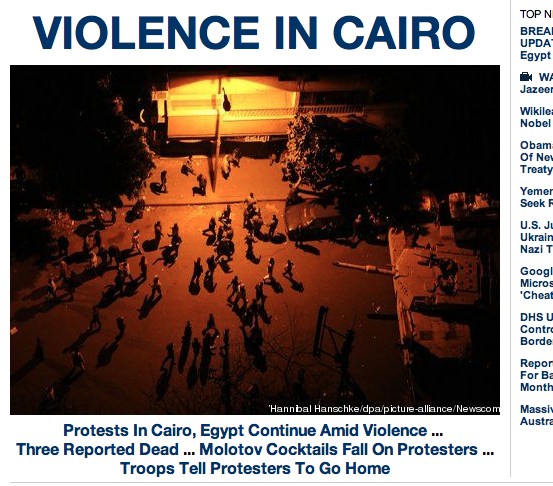

Surprise became the operative mode for No. 1. After Cage got it, Rauschenberg was staying at Cage’s apartment while his loft was being fumigated for bedbugs, and he surprised/thanked the composer by painting over No. 1 with black enamel and collaging it with black-painted newspaper. According to Michael Kimmelman’s obit for Rauschenberg, “When Cage returned, he was not amused.”

Christie’s says this happened “a year or so later,” but Kimmelman says “As Mr. Rauschenberg liked to tell the story,” it was right after the Parsons show, which closed June 2nd. Rauschenberg and Weil’s son Christopher was born in July. And according to his 1976 chronology, he/they went to Black Mountain College in the “early part of the fall.”

But the Black Paintings, which seem to have followed the White Paintings, are dated as late 1951-1952. [Kimmelman reverses them, but Hopps’s catalogue quotes an October 1951 letter from Bob to Parsons talking about them as faits accomplis. I thought Kenneth Silverman’s John Cage bio Begin Again might help, but it is hopelessly inaccurate about dates for Rauschenberg’s works, and he doesn’t seem that interested in chronologies, either. He jumbles events from several years into single paragraphs, or omits dates altogether. And he doesn’t mention the bedbug thing at all. But anyway. I think the Black Paintings come to a hard stop in 1952. Rauschenberg was back at BMC in the summer when his white paintings were included in Cage’s formative Theater Piece #1 and subsequently contributed to Cage’s composition of 4’33”. Then he left for Europe that fall with Cy Twombly, leaving his soon-to-be-ex-wife and son behind.]

And so, perhaps unsurprisingly, the details and reported dates and circumstances of paintings created during this rather complicated time are themselves rather complicated.

A comment the artist made to Calvin Tomkins in 1980 about the Black Paintings seems apt:

“I was interested in getting complexity without their revealing much. In the fact that there was much to see but not much shown.”

But wait, there’s more!

This famous painting was subsequently again modified in 1985, when, it had become in need of some restoration. Rauschenberg chose to paint it completely all over in black again and bestowed upon it an accompanying note referring to the, by this time, historic and continuing dialogue that Cage and Rauschenberg had then enjoyed in both their art and their lives for over thirty years. The note reads: “This is part of the history of this single canvas – I hope the dialogue continues for many more years. I will if John dares, love Bob Rauschenberg.”

While it’s tough for the collector–or the auction house–who wants their 1951 painting to look old, the conception of a canvas as a constant site of activity, dialogue, and collaboration is pretty fascinating.

As Rauschenberg said of Short Circuit in 1967, when he showed it for the first time in over a decade:

This collage is a documentation of a particular event at a particular time and is still being affected. It is a double document.

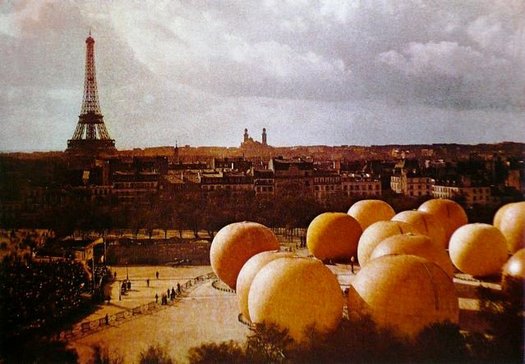

Double and then some. Short Circuit, of course, included a program from an early Cage concert [which I’m trying to identify, btw] and a painting by Weil, though in 1967-8, the painting was hidden behind a nailed-shut cabinet door. [There was also that Ray Johnson collage, which contains a reproduction of a Renaissance nude.]

Anyway, I would think that with current imaging technologies, it would be possible, if not trivial, to examine Rauschenberg’s No. 1 for traces of the three paintings it used to be. Perhaps such an investigation could be combined with a closer reconstruction of the pivotal period in which it was created. As Rauschenberg himself put it, there is much to see, but not much shown.