And so far, I can’t find it anywhere:

UEZ: when your work first started to appear and was classified as Conceptual art, did you have a secure visual language which you knew would be viable over time? Or could you have arrived at completely different forms of presentation, or made your photographs the basis for videos?

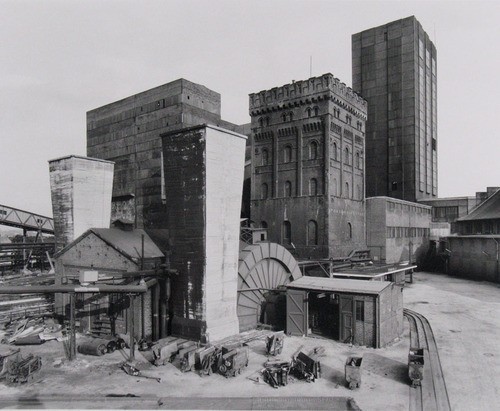

BB: We did make a film once, on the Hannover mine.

HB: Actually, there’s no need at all to talk about failures.

BB: Because that was such an enormous complex. We made a film about it because we wanted to show the atmosphere. Then we looked at the shots, still uncut, and were totally disappointed.

UEZ: How did you make the film?

HB: We borrowed a 16mm camera from Sigmar Polke. The advisor was Gary Schum, in part, who has made a load of beautiful artist films, with Gilbert and George, for example. The idea was that this colliery was not a tightly knit conglomerate, as is usually the case, but rather a diffuse structure held together by belts, by roads.

BB: The atmospheric element was important. On top of that, we were in a hurry. We thought that if we photographed our way through the whole plant, it would take years. Then we made the film in two or three days.

HB: The thought was to drive through this very extensive industrial estate, to show the connections among preparation plant, winding tower, power plant and cokery. But as it turned out, there was so little movement there that the only movement in the film was provided by the camera.

UEZ: Because the colliery was already shut down?

HB: No. Strictly speaking, if you look at a mine like this, the only thing that moves is the wheel of the winding tower. I was thinking at the time of the early Charlie Chaplin films, where the camera sits on the tripod and everything else moves in front of it. Or Hitchcock’s film Rope, which takes place in one room.

UEZ: How strange that you give us these examples, as in fact you didn’t let the camera stay still.

HB: But panning the camera, up and down, right and left–that was no good.

UEZ: When did this experiment take place?

BB: 1973-74.

UEZ: Did you destroy the film in the end?

BB: No.

UEZ: We’re talking about a black-and-white film?

BB: No, it was in color.

That’s from an interview the Bechers did with Ulf Erdmann Ziegler in 2000. It was originally published in Art in America in 2002.

The Hannover Coal Mine was one of ten mining sites the Bechers photographed as early as 1966, but with a concentration in 1971-74, and presented in an “un-Becheresque” way: by site, not by typology. The Van Abbemuseum acquired one portfolio, 85 prints of the Hannibal Mine in Bochum, in 1976, but most of the hundreds of images from each site were unpublished negatives.

And at the time of the interview, the SK-Stiftung in Cologne [which houses the couple’s portfolio archive], began working to process and print images. They did a show, which traveled to the Huis Marseille in the Netherlands. And a catalogue, Zeche Hannibal (Coal Mine Hannibal), which sounds rather interesting.

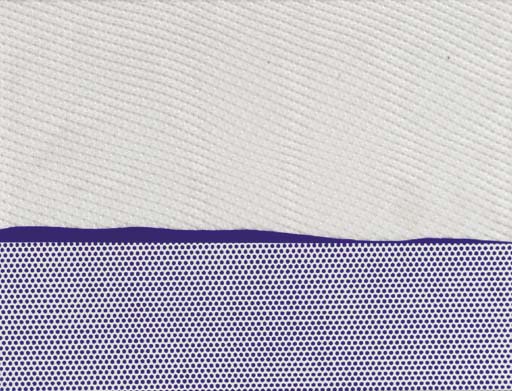

Hannover Mine 1/2/5, Bochum-Hordel, Ruhr Region, Germany, 1973, Bernd & Hilla Becher [via moma]

As it happens, 200 of over 600 photos the Bechers made at Hannover have just been published in their own book. Zeche Hannover (Hannover Coal Mine) came out in Germany in July.

And it looks like MoMA acquired a selection of the Bechers’ mine landscapes in 2008. When seen together, they end up forming a higher-level series, a typology, not of structure, but of site. So they’re looking more Becheresque all the time. I’d still like to see that film, though.

First museum shows for

First museum shows for