I cannot believe this has under 1,000 views. I’m only about 8:00 into this YouTube video, and already, Viktor Pinchuk is my hero. While anyone with a yacht or a palazzo could assemble a tranche of the art world powerful on the Grand Canal, only Pinchuk’s inspiring artistic vision can bring them all to Kiev. Well, I’m pretty sure it’s his vision they’re coming for.

Come for the vision, stay for the historic chance to have Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Andreas Gursky, and Takashi Murakami together on stage, answering incisive questions from Ryan Seacrest’s Ukrainian doppelganger. And the pitch for free Prada.

Ah, yes, I just got to the end: “Thank you to the thousands, the hundreds of thousands watching online!” It Gets Better!

Cinthia Marcelle receives Main Prize on FGAP Award Ceremony [ThePinchukArtCentre’s YouTube channel, via Gavin Brown’s GBlogÉ, pronounced like the French, Blo-ZHAY]

Category: inspiration

Richter’s Balls, Regrets

So I’m reading along in my new copy of Gerhard Richter: Writings 1961-2007–which is pretty awesome, and which does appear to supersede the artist’s previous collected writings, The Daily Practice of Painting, which is good to know, but really, what to do with all this information?–and I come across this discussion of glass and mirrors and readymades in a 1993 interview with Hans Ulrich Obrist, and I’m like, holy crap!

When did you first use mirrors?

In 1981, I think, for the Kunsthalle in Dusseldorf. Before that I designed a mirror room for Kasper Koenig’s Westkunst show, but it was never built. All that exists is the design–four mirrors for one room.

The Steel Balls were also declared to be mirrors

It’s strange about those Steel Balls, because I once said that a ball was the most ridiculous sculpture that I could imagine.

If one makes it oneself.

Perhaps even as an object, because a sphere has this idiotic perfection. I don’t know why I now like it.

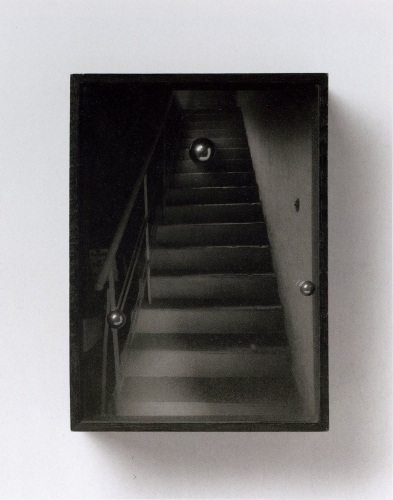

Richter’s mirror Steel Balls? Whew, never mind, they turn out–I think–to be Kugelobjekt, 1970, these odd, little postcard-sized objects, three steel ball bearings suspended in plexiglass in a shadowboxed photo of a staircase.

Kugelobjekt I, 1970, image: gerhard-richter.com

And anyway, on the next page, Richter explains how all the work on the dimensions and framing and installation of 4 Panes of Glass meant it’s “not a readymade, any more than Duchamp’s Large Glass is,” when he goes,

At one point I nearly bought a readymade. It was a motor-driven clown doll, about 1.5 metres tall, which stood up and then collapsed into itself. It cost over 600 DM at that time, and I couldn’t afford it. Sometimes I regret not having bought that clown.

You would have exhibited it just like that, as an uncorrected readymade?

Just like that. There are just a few rare cases when one regrets not having done a thing, and that’s one of them. Otherwise, I would have forgotten it long ago.

And I’m like, the clown! the clown! I swear, I’d written about it before, but I can’t find it anywhere. And then I realize I’d written about it for the NY Times in 2005.

Previous most ridiculous sculptures I could imagine: The International Prototype Kilogram or Le Grand K, and the Avogadro Project

UPDATE:, uh, no. Richter has more balls than I thought.

Mientras Tanto En Mexico,

While poking around online about Tate Modern’s version of the Gabriel Orozco retrospective, I found this rather incredible letter from 2009, written, apparently by Orozco himself, to his dealer Jose Kuri. The letter is an ostensibily-but-not-really private round in an ongoing, public, critical battle for some kind of primacy within the Mexican art world.

Orozco defends and praises his own success and innovation–to his own dealer–while slamming both other artists [cough, Santiago Sierra, Francis Alys] and their critic/curatorial champions [Cuauhtémoc Medina, who I will be adding to the greg.org art pronunciation list shortly.]

Anyway, this kind of veiled subtexts with an apparent academic impartiality and a deficient documentation, derive from a cheap historicism, where the talent of the individual to understand his/her moment, and to do the things that he feels like it and with it finding new art for life and for the work, will never be the reason for his success. If anything, it can seem incredible to those Mexicans, that a co-national has innovated and influenced other artists in the world, which, although is not mentioned -in the breakdown of the ingredients for my success-, is a measure and perhaps the main reason for the success of my work in this years. Novelty, not exoticism, is what makes fortune. And the one that makes something before the others becomes an essential reference point. Success came after the creation of something new… which was successful.

Wow, OK. I have been a diehard fan of Orozco’s work for almost 20 years now; I still see him as having a formative influence on my eye, and on the whole way I see the world in relation to art. Or to his art. And maybe I just don’t/can’t appreciate the nationalist/politicized context in which this debate is occurring.

But I’m trying to come up with examples of other artists who aren’t Julian Schnabel who take such on the record personal affront. I guess Rob Storr loves to deal out the smackdowns, too. Anyway, the Centre For The Aesthetic Revolution has the whole thing. Definitely check it out.

GABRIEL OROZCO ‘THE SECRET OF HIS MIRACULOUS SUCCESS’ A LETTER TO HIS GALLERIST IN DEFENSE OF SOME OF HIS CRITICS [centrefortheaestheticrevolution]

Also from the Centre For The Aesthetic Revolution, word that the Hotel Palenque has finished the renovations, and is open for business. This apparently happened some time between Robert Smithson’s drunken slide lecture about it in 1972 and the arrival of the Google Street View coche.

Yves Klein, Ex-Voto Ex-Monastero

Sister Andreina holding Yves Klein’s ex-voto for Santa Rita di Cascia in 1999, photo: David Bordes

I get the sense that in the contemporary art world, an artist’s religiosity or spirituality is often perceived as an obstacle, an eccentricity to be indulged when they’re around, but to be politely ignored in serious discussion. That goes for John McCracken, Anne Truitt, Marina Abramovic, a bunch of others, I’m sure, and the one who made me think of it just now: Yves Klein. When the artist’s widow Rotraut Klein-Moquay spoke at the Hirshhorn Museum’s retrospective last spring, it was clear that she was operating on a different, more spiritually attuned plane than the show’s clearly uncomfortable curator, Kerry Brougher. [Though watching Brougher, his co-curator Philippe Vergne, and the Klein Archive’s David Moquay at the Walker a few months later, exasperated interruption may be the only way to get a word in edgewise with the rambling Moquays.]

Anyway, Vergne takes it all in stride. In an interview with the Walker’s Julie Caniglia, he tells about securing the loan of one of the most interesting and unusual pieces in the retrospective, a 1961 ex-voto which Klein left at the monastery of Santa Rita di Cascia. It’s like a little retrospective in a box, a boite en valise.

Julie Caniglia

Speaking of striving, you literally went out of your way so that Ex-Voto would be a part of the exhibition. Can you talk about how this loan was carried out?

Vergne

Klein made an extraordinary gesture with this artwork and that’s reflected in how it’s treated by the monastery. I don’t think the Mother Superior would have allowed it to leave the convent without a meeting with one of the exhibition organizers. She was basically saying to us curators, “If you really want this work of art, you’re going to have to come and tell me why. It cannot be treated as one more object. You’re not going to just send a loan form, you’re going to have to come and sweat a little bit because this object is extremely important.”

On the other hand, she was kind enough to meet me at a cloistered convent in Rome so I wouldn’t have to make the long drive to her convent at Cascia. We were in a little room accessible to visitors, but divided wall-to-wall by a table: one side for guests and the other for nuns. They brought me coffee and cookies. Through a translator, we entered this conversation talking about Klein’s work and how important it was to have the Ex-Voto in the exhibition. Then we read the entire loan document word for word, all of the details about insurance and transport, everything. It was really like a ritual. Then we had a conversation about immaterial sensibility.

I also got to tell her a story about the well-known Leap into the Void photo–how the house that Klein leapt from outside Paris later became a church dedicated to Saint Rita, through absolutely no relationship with Klein. I thought this was extraordinary, but she said, “No, it’s normal.” I thought she meant for Klein, but she said, “No, for him,” pointing her finger to the sky.

Before I met with the Mother Superior I got to see a part of the convent closed off to the public where some absolutely gorgeous 13th-century frescoes were being restored. That, too, became part of the Yves Klein exhibition for me. I see it as an example of Klein’s immaterial sensibility: I am made of all these little layers of experience, which came together in the making of the exhibition.

Saint Rita is known as the patron saint of lost causes, and was a favorite object of Klein’s devotion and ritualistic interest. He apparently made the ex-voto while experiencing something like painter’s block, and he left it during one of several pilgrimages to Cascia. It was only discovered in 1980, during a renovation at the monastery following an earthquake. It was included in the Centre Pompidou’s 2006 retrospective, but it will return to Cascia after the Klein exhibition closes at the Walker this weekend. Pilgrims, your time is running out.

Yves Klein and the patron saint of lost causes [walkerart.org, thanks to Matt at RO/LU]

Haven’t Found Tacita Dean’s Sound Mirrors Yet

Maybe it was me looking for Tacita Dean’s Sound Mirrors that brought me there, but David Williams’ 2009 post at Skywritings about Dean, Derek Jarman, Dungeness, gardens, Tehching Hsieh is pretty wonderful:

Everything here has been found, salvaged, re-cycled from this sea-edge place, and is both displaced and quite at home. A manifest testament to qualities of patience, economy, playful invention and a quiet contemplative thusness. For the garden stages a deep acceptance of being here in all modesty and attentiveness. Taking time to make space. Slow time, still moves. A bricoleur Picasso meets the Zen garden.

Jarman bought the house in 1986 for £750; he was scouting for bluebells with Tilda Swinton and Keith Collins for a film shoot. He called it his ‘paradise at the fifth quarter’, a place where he could walk in the ‘Gethsemane and Eden’ of his garden and ‘hold the hands of dead friends’ (Garden).

(Once, when my mother was very ill in hospital, she told me that her mother had just visited her, what a shame I’d missed her. She had knocked on the window, told her that she should ‘come out into the garden’, it was good out there, and it was time. Her mother had died more than ten years beforehand).

Still looking for that Sound Mirrors piece. I suppose I should just go to the gallery.

In fact, skywritings is good all over. [sky-writings.blogspot.com]

On Stage

In 2002, as I was still trying on various kinds of public writing, I tried to capture the transformative experience of listening to–no, experience is the better word–On Kawara’s One Million Years.

That post was even titled like a screenplay: “Setting: Fredericianum, Documenta II, Kassel.”

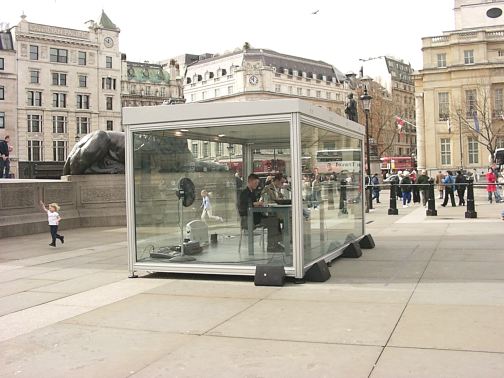

image via mightymac

In April 2004, South London Gallery staged a week-long, round-the-clock marathon reading of One Million Years in Trafalgar Square. Many passersby unfavorably compared Kawara’s volunteer readers in their glass box to David Blaine, who had, just a few months before, spent 40 highly publicized days in a plexiglass cube suspended from a crane next to the Thames.

In 2009, when David Zwirner staged a reading/recording of One Million Years, Brian Sholis wrote touchingly and with great acuity about the experience of reading the years 79,936 AD – 80,495 AD with his then-fiancee.

And yet only just now, somewhere between finding Jerry Saltz’s characteristically gossipy, angst-ridden account of reading in the same show, and watching this comical YouTube video of Martin C. de Waal, a Dutch club kid/stylist/Orlan-style conceptual self-portraitist and his dance remix singing partner Marina Prins [!] getting all dolled up for their reading on the open platform at the Stedelijk–the one we’d been standing on a few weeks ago–do I realize the powerful performative essence of Kawara’s piece. And with less than a hundred of an anticipated 2,700+ CDs burned, it’s barely even begun.

The effect of living in a post-Marina world, I suppose

Q For Institutionally Affiliated Readers Of greg.org: Res 10?

If you can see the full text of “On Collaboration In Art,” David Shapiro’s conversation with John Cage, published in the Autumn 1985 issue, (No. 10) of Res: Anthropology and Aesthetics, perhaps you can tell me if it does, in fact, discuss Rauschenberg and Johns’ work on Short Circuit as the web-based search appears to indicate?

Thanks!

On Collaboration in Art: A Conversation with David Shapiro

David Shapiro and John Cage

RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics

No. 10 (Autumn, 1985), pp. 103-116 [jstor.org]

update: Thanks to greg.org readers B and G, we know the answer is yes, yes it does, and wow, very interesting. Here is Shapiro asking his friend Cage about Black Mountain and how he perceives collaboration:

DS: So collaboration also implied simultaneity?

JC: That’s all it really means to me.

DS: Two things happening at the same time.

JC: That is their relationship.

DS: Bob Rauschenberg often seems optimistic, inclusive, as if he’s marrying the whole world, like permitting Jasper Johns’s flag to be inside a larger sculpture. It seems like a sign of generosity. He sometimes seems generous in his collaborative spirit. You don’t think of it as necessarily emotionally generous to collaborate? Is it not a sign of charity?

JC: No. It’s a willingness to have your work experienced at the same time other work is experienced. I’m being careful not to use the expression “willingness to come together,” because there’s no coming together really. It’s two different different things that if they do come together at all, they come together where Marcel [Duchamp] said a work of art was completed, in the observer. But the two people who are collaborating are not observers until they can be. Then, when they are observers, they’re no longer collaborators.

I was going to add italics for the rather salient language these folks were using, but well, where to stop?

Hirshhorn curator Cynthia McCabe was there, too, and Shapiro’s wife, the architect Lindsay Stamm Shapiro. McCabe really wanted Short Circuit for the Hirshhorn’s 1985 exhibition, “Artistic Collaboration in the Twentieth Century”:

CM: We just had a very sad experience looking at the Rauschenberg Short Circuit that Jasper had done with him and Susan Weill [sic]. It’s now in a state of real disrepair. It’s so important for this exhibition.

LS: Where is it?

DS: It’s in Rauschenberg’s studio, but Johns’s flag had been stolen at the place. It had been shown at Finch College. It is like a wing to an altarpiece, and inside was a Susan Weill. I’m sure you’ve seen it.

CM: There was a little sticker in there, I’m trying to think of which was the work, it says “Cage.”

DS: Yes, it has a little collage mentioning a performance that you had done. I think with David Tudor. When David Tudor does chord clusters in the record indeterminacies, was that collaborative or completely mapped out by you, so he’s the performer?

JC: He’s playing the Solo for Piano from the Concert for Piano and Orchestra.

I’m An IBMer’s Son

Rather sensibly, IBM tapped Errol Morris to create films commemorating the company’s 100th anniversary. Even when a guy delivers slightly underwhelming lines like, “We changed the way the world shops,” this one, They Were There, is pretty awesome.

My dad worked for IBM for decades, long enough for me to have a bias for white dress shirts ingrained into my psyche. And I did interview Errol Morris that one time.

And while I can understand why it’s not in there, I do kind of wish the company would, when celebrating its history, acknowledge the longstanding, critical role IBM, its technology, and its German subsidiary played in the Holocaust. Because they were there. And that’s certainly more important than changing the way the world shops.

IBM Centennial Film: They Were There – People who changed the way the world works [youtube via daringfireball]

Stedenboek

This just in from the greg.org Department of Stunningly Beautiful Digitized Maps of The Netherlands:

Bibliodyssey has some highlights from the National Library of the Netherlands’ fresh upload one of the rarest and most beautiful atlases in history, mid-17th century Dutch cartographer Frederik de Wit’s Stedenboek, or Book of Cities.

Who knew that the Dutch had such a long, rich, aesthetically awesome history of defense-related polygonal alterations of the urban landscape?

At least maybe now we have some idea where that crazy camo blob in Nordwijk came from:

Stedenboek [kb.nl]

Dutch City Atlas [bibliodyssey]

What I Looked In 2007 & Again Just Now: Myron Stout

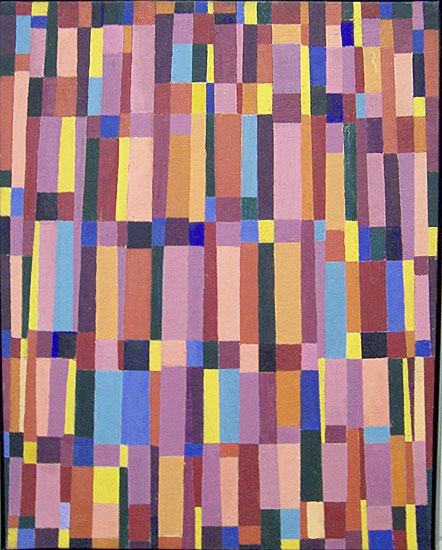

Doug Ashford ended the 2009 presentation I just posted about, “Abstraction as the onset of the real,” with a slide of this beautiful painting, Untitled, 1950 (May 20) by Myron Stout.

Washburn Gallery had a sweet little early Stout show in 2007, which I’d completely forgotten about. Back when he was still writing about art, NY Times chief art critic Michael Kimmelman reviewed the show:

…his mentor remained Hans Hofmann, who helped him see how to construct a purely abstract picture, while his great inspiration was Mondrian, about whom Stout observed that “the tangible and sensational world was still the raw material for the universality which he would create for himself.” In other words, Mondrian, like Stout, remained firmly connected to nature and the real world.

Things that happened in 2007 can seem so long ago and far away. I need to hustle up some Stouts to look at, pronto.

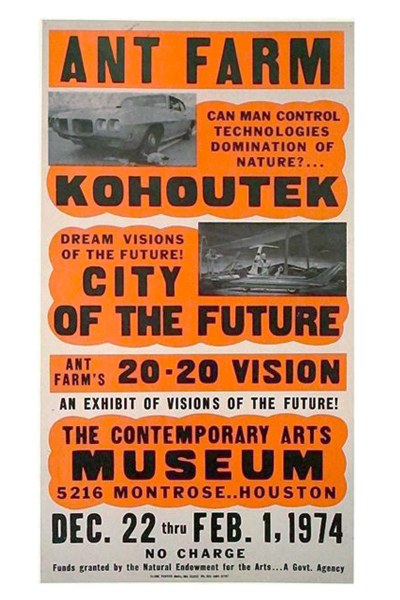

Ant Farm 20:20 Kohoutek Letterpress

I’ve been deep in the commercial letterpress lately, and neglecting my Ant Farm. Fortunately, Mondo Blogo is there to bring me back in line, with this awesome poster the Farmers made for 20:20 Vision, their show at CAMH.

20:20 featured a Dollhouse of the Future named Kohoutek, after a comet that was supposed to crash into the earth or something, sending hippies into an apocalyptic panic, but it missed, bumming everyone out. In Kohoutek’s Living Room of the Future, naked Barbies lounge around on biomorphic sofas watching a live data feed from SkyLab, seemingly unaware that they’re being raised as food for the comet-surviving ants.

According to a review in Architectural Forum, there were 20:20 t-shirts as well as posters for sale. I’m dispatching my army of Houston vintage pickers forthwith.

And even though Houston was the first place Ant Farm unveiled their plans for the Dolphin Embassy, I think my favorite part is there at the bottom:

“Funds granted by the National Endowment for the Arts… A Govt. Agency”

ant farm: sex, drugs, rock & roll, cars, dolphins & architecture [mondo-blogo, thanks andy]

Previously: Cue the Dolphin Embassy [greg.org]

Thomas Struth On Gerhard Richter

The Minneapolis Institute of Arts has a sweet Struth photo of the Cologne Cathedral, and somehow, Gerhard Richter’s pixel-style stained glass window is not the most awesome thing about it. Also, is that a mop on that ledge in the foreground?

See a larger image, plus the photo in situ, at the top of the MIA’s grand staircase [artsmia.org via eyeteeth]

Van Gogh, Haring, Razzle Dazzle: Car Camo Wraps

I love it when a tossed-off plan comes together. In this case, it’s the idea of artist-designed vinyl car wraps. And camo.

The Times had a great story about auto spyshots, and the increasing use of camouflage vinyl wraps on test cars. Some of the wraps seem designed to thwart a spy photographer’s focus, or at least to obscure the contours and details of the car.

The different patterns are discussed as resembling “a Keith Haring painting,” and “World War I ‘dazzle ships,'” or as sporting the swirly, painterly “Van Gogh Look.”

It should only be a matter of time before a collection of contemporary artist vinyl wraps hits the streets. Right?

Secret Cars Kept Under Wraps, in Public [nyt via slow and steady wins the race]

Previously:

The Jeff Koons wrapped BMW

Vinyl wrapped art car: Hirst]

First or worst? Peter Max decal car c. 1968

Razzle Dazzle and Dutch Google Maps camo

OG WWI dazzle design and the Koons revival

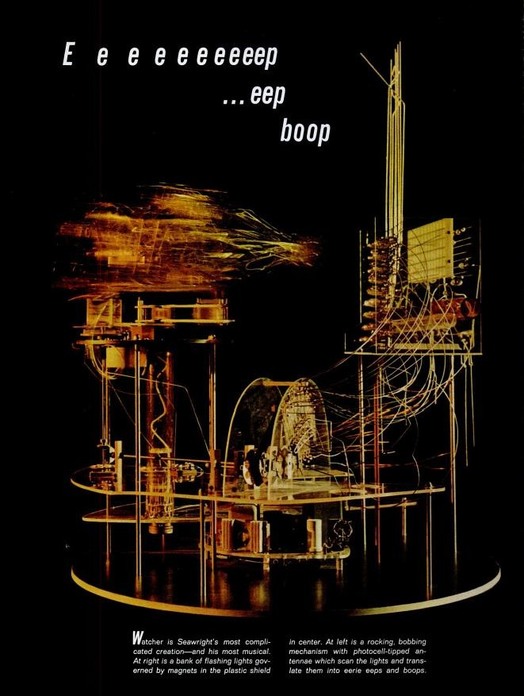

Whoa, James Seawright

It’s crazy sometimes how long it takes to see what’s right in front of your face. I’ve been thisclose to artist James Seawright’s kinetic and electronic sculptures over the last couple of years, and yet I only really discovered them yesterday.

Seawright, who was for a long time the head of visual arts at Princeton, began making Bauhaus-inspired light and sound performance works with his dancer wife in the early 1960s. Bauhaus in this case meant Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, whose Light Space Modulator has been much discussed around here.

Trained as an engineer, Seawright began taking sculpture classes at the Art Students League in New York, and scored a solo show at Stable Gallery in 1966. Among his awesome work in that show: Watcher (1965) [above, from a 1967 LIFE Magazine spread.]

Like much of Seawright’s work, Watcher is designed to activate and react to the presence of the viewer–or to itself–via photovoltaic sensors. It looks remarkably similar, both formally and functionally, to the Eames Solar Do-Nothing Machine (1958).

After his Stable Gallery show, Seawright was involved in shows at Howard Wise, and was one of a handful of artists–along with Allan Kaprow, Otto Piene and Heinz Mack–to participate in The Medium is The Medium, an early experiment in video art/”tele-Happenings” produced by WGBH in 1969. Which I now must watch again, for the Seawright part.

James Seawright [wikipedia]

seawright.net [the artist’s portfolio site]

Dance + The Whole World = The Whole World

Via Ubu comes a provocative essay, “Constructed Anarchy,” from the poet and John Cage critic Marjorie Perloff. She takes the death of Merce Cunningham and the company’s plans to dissolve after a worldwide farewell tour as an opportunity to ask a tough question of Cunningham’s and Cage’s philosophy: basically, if art is life, what happens to it after you’re dead?

When in June 2010 I had the chance to see Roaratorio performed at the Disney Concert Hall–a beautiful Roaratorio but no longer graced by the presence on stage of Merce or by the actual speaking voice of John Cage–what seemed especially remarkable was the tight formal structure of a composition once billed (both in its radio and dance incarnations) as an anarchic Irish Circus, bursting with random sounds and unforeseen events. For, however differential the leg, arm, and torso movements of the individual dancers (sometimes in pairs or threes, sometimes alone), all are metonymically related in a network of family resemblances, and all are, as the charts show, mathematically organized. Yet wasn’t it Cage who defined his music as “purposeless play”–“not an attempt to bring order out of chaos . . . but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord”? And wasn’t it Cunningham who insisted that dance “is not meant to represent something else, whether psychological, literary, or aesthetic. It relates much more to everyday experience, daily life, watching people as they move in the streets”?

The very life we’re living: the Gelassenheit so seemingly central to Cage-Cunningham was hardly anarchic, much less unpredictable. But their own statements, and hence the critical writings about their work, have regularly insisted on what Joan Retallack, in her seminal series of conversations with Cage, calls “an aesthetic pragmatics of everyday life.” “[Cage] told me,” she recalls in her Introduction, that “the art that he valued was not separated from the rest of life. . . . The so-called gap between art and life didn’t have to exist” (Musicage xix-xx). And Cunningham repeatedly made the same point, using traditional ballet as contrast.

Or that’s how it used to be.

It sounds convincing: to see RainForest or Roadrunners, Channels/ Inserts or Beach Birds, is to perceive that there is no central focus or storyline, no prima ballerina flanked by a corps de ballet, no symmetry or detectable unifying principle. But if the dancers are free to introduce their own variations and tempo, if the piece is as non-hierarchical and collaborative as Merce suggests, why has each work (dance and music) been plotted out geometrically and arithmetically? Why have the dancers received so much less acclaim than Cunningham himself, in his role as director /producer /choreographer? And why has the decision been made that the ensemble will not be able to function without him? Similar questions can be put about Cage’s work: is his recorded voice reading Roaratorio essential to the work? Can a “decentered” Cage Musicircus perform without Cage?

The more we probe such Cunningham-Cage concepts as “free form” or “anarchy,” the more apparent it becomes that theirs is an anarchy that is carefully simulated. Their works are by no means “happenings,” in Allan Kaprow’s sense of the word, nor is Cunningham producing performance art.

As in Duchamp’s case, no “accident” is really accidental, and discipline is central. [emphasis added because, yow, kinda harsh]

Perloff’s argument is definitely worth a read, and she had a front row seat–and she quotes longtime Merce collaborator Carolyn Brown and others–on Merce and Cage’s egos and steely artistic wills, which seem to undermine a carefully cultivated [or at least prevailing] laissez-faire, see-what-happens image.

But I’m just half-informed enough to take issue with Perloff’s takedown. She sets up seeming contradictions between professions of randomness and artistic control, but I think that’s false and unfair. Cage wasn’t an evangelist for randomness, nor for anarchy, but for chance and chance operations. And there’s a meaningful difference that I suspect Perloff knows well.

Randomness is whatever happens, but chance operations is a tool for determining what happens. Perhaps Cage and Cunningham’s meant their obliteration of the distinction between art and life, between music and sound, between dance and movement, to be a production strategy for the artist, not a life strategy the audience.

Constructed Anarchy [lanaturnerjournal.com via ubu]

Interesting/related, and the 2nd time in 2 days to see Cage compared to Warhol: Ubu founder Kenneth Goldsmith’s 1992 review of Perloff’s first posthumous Cage essay. [electronic poetry center]