“Obviously, it’s a clock, the whole project is a clock. It’s managed by the moon,” said Darren Almond of his Fullmoon Photos series in this seven-year-old video from the Louisiana Museum.

It’s been a minute [h/t @br_tton] since I remember how thoughtful and interesting I find Almond’s work, then he comes up with this:

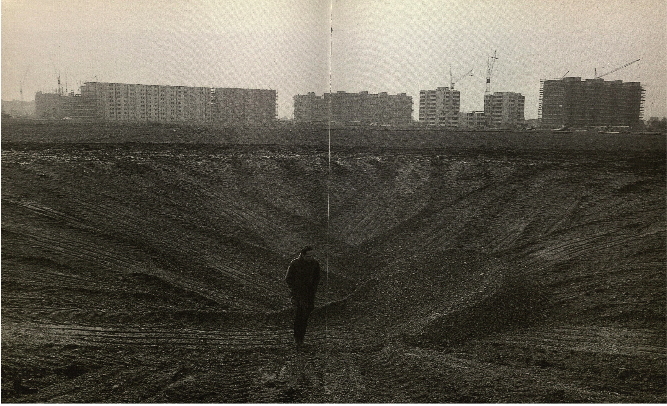

It started off as a romantic gesture, an inquisitive point. Then it became a kind of controlled concept. But then I was involved in this meditation by moonlight. I was involved in the act of making the photograph. Then my life was becoming connected and had a strong relationship with the landscape. I was going off into this landscape we are no longer familiar with, which is the landscape of the night, away from all the pollution, the light pollution that we’ve generated, that we surrender ourselves with.

Recognizing the change we undergo by the making of the work. It’s something I think about a lot, at various levels. I have unrealized projects that would, I recognize, consume me, were I actually to attempt to realize them. Some of them are maybe even unrealizable by design. There are tabs open for a project I actually consider doing. There are tabs open for posts I have yet to write. These are the impacts of writing and connecting as I do.

In a 2017 interview for MUDAM he talked about the end of the project, and what had been invisible to him before:

In 2013, I was in Patagonia. There, the atmosphere is very clear, there’s far less light pollution and you’re able to literally see the colours of the night sky. This experience marked a cut-off point for me. After twenty years of traversing the globe and looking through the lens of a camera at what I could see in front of me, I suddenly felt that I needed to approach landscapes that I couldn’t see, landscapes beyond visibility, but through the visual somehow, using a tool or a mechanism to see into the shadows, to enlighten the shadows that lie before us.

What followed was Timescape paintings, “Inspired by views of the deeper space…[that] materialise the impression felt when faced with this night sky,” and “that evoke the visible confines of the cosmos,” according to MUDAM. “Despite their apparent blackness, these paintings are obtained from numerous layers of different flat colours applied successively on an aluminium support.”

So twenty years of meditating by moonlight and traveling to forgotten landscapes led Almond to become an abstract painter trying to capture the impression of looking up at the night sky. I was worried this romantic project didn’t sound like progress, but then I remembered we exist within cycles of time, some of which are made visible by moonlight, and some which only come into view after many trips around the sun.