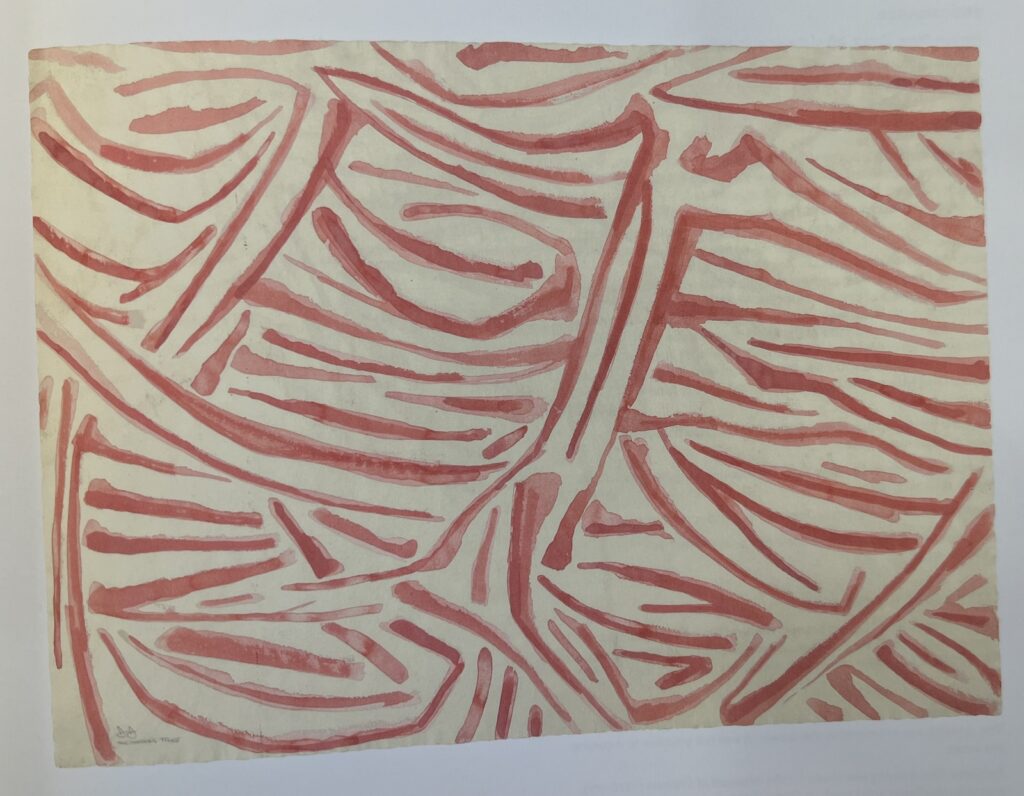

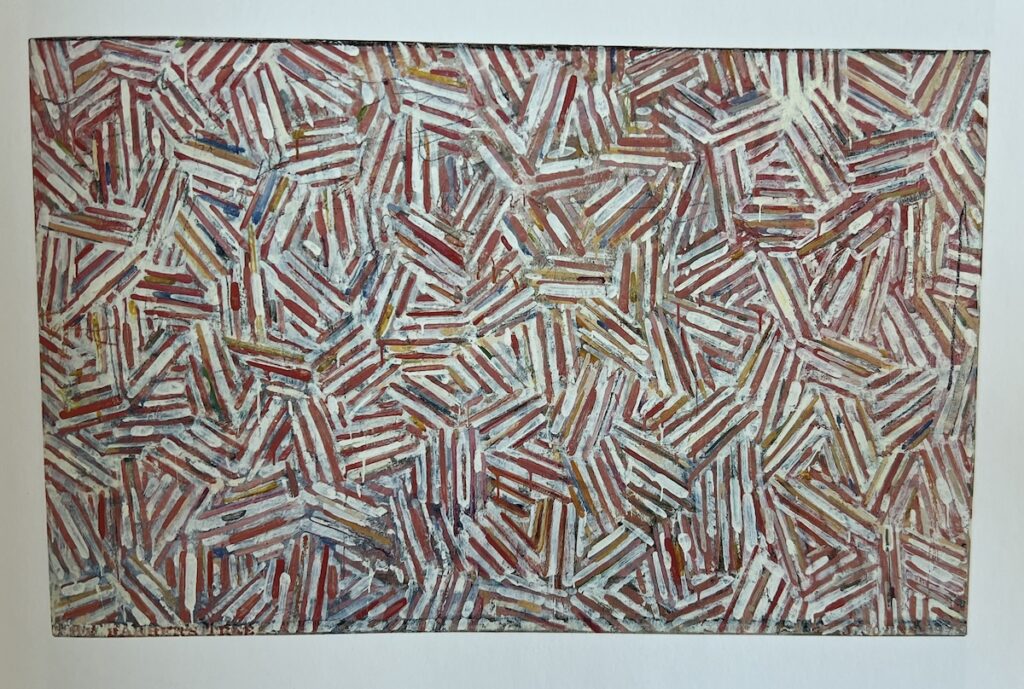

Maybe not being able to find the flagstones motif source, a Harlem wall glimpsed once through a taxi window and then lost, changed Jasper Johns’ approach a bit. Because by 1973, he did take note of the inspiration The Barber’s Tree. At least for the sketch [above], if not the painting, which turned out to be a mostly typical crosshatch motif executed in red and white.

And now we know what Johns knew.

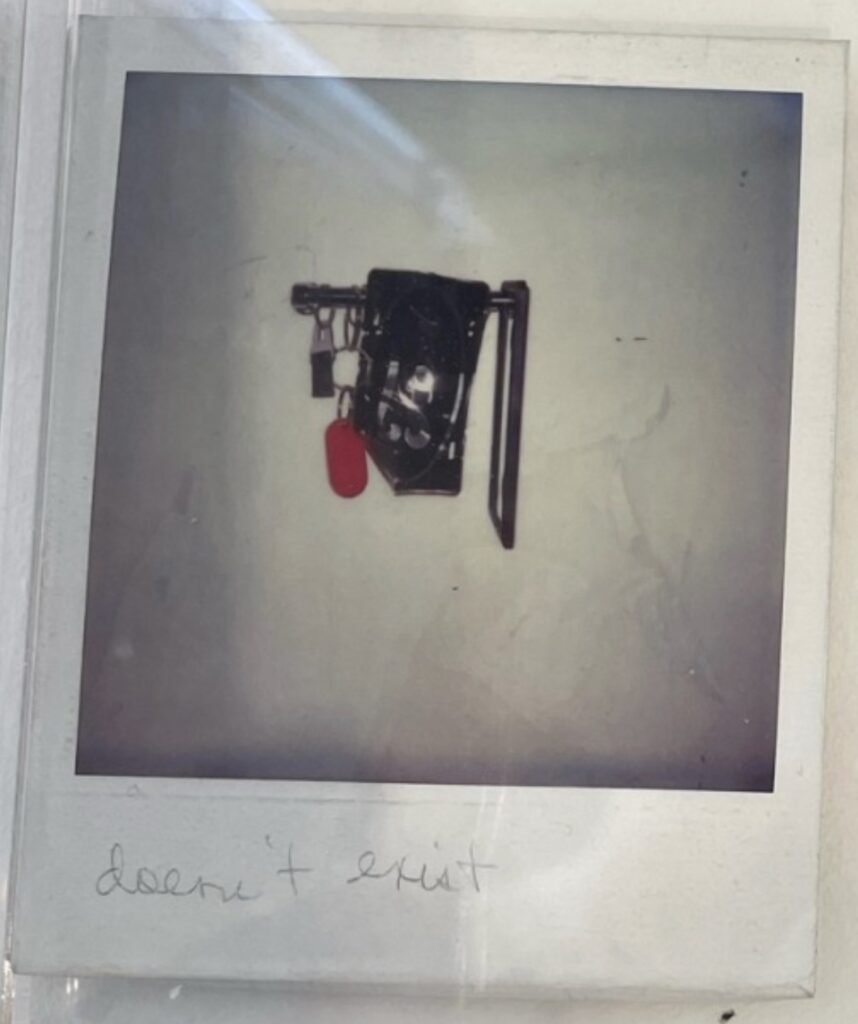

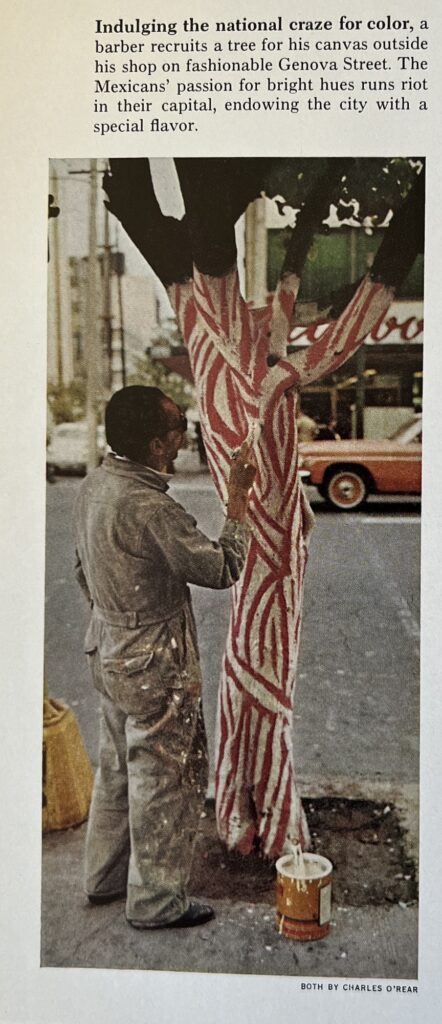

Here is photographer Charles O’Rear’s image from “Mexico: The City That Founded A Nation,” a dispatch by Louis de la Haba and Albert Moldvay from the May 1973 issue of National Geographic.

It is small, and slight, but indeed eye-catching. It’s not clear who is responsible for this cringe caption, though, about “Indulging the national craze for color” and “The Mexicans’ passion for bright hues,” when every barber pole north of the border has the same color scheme.

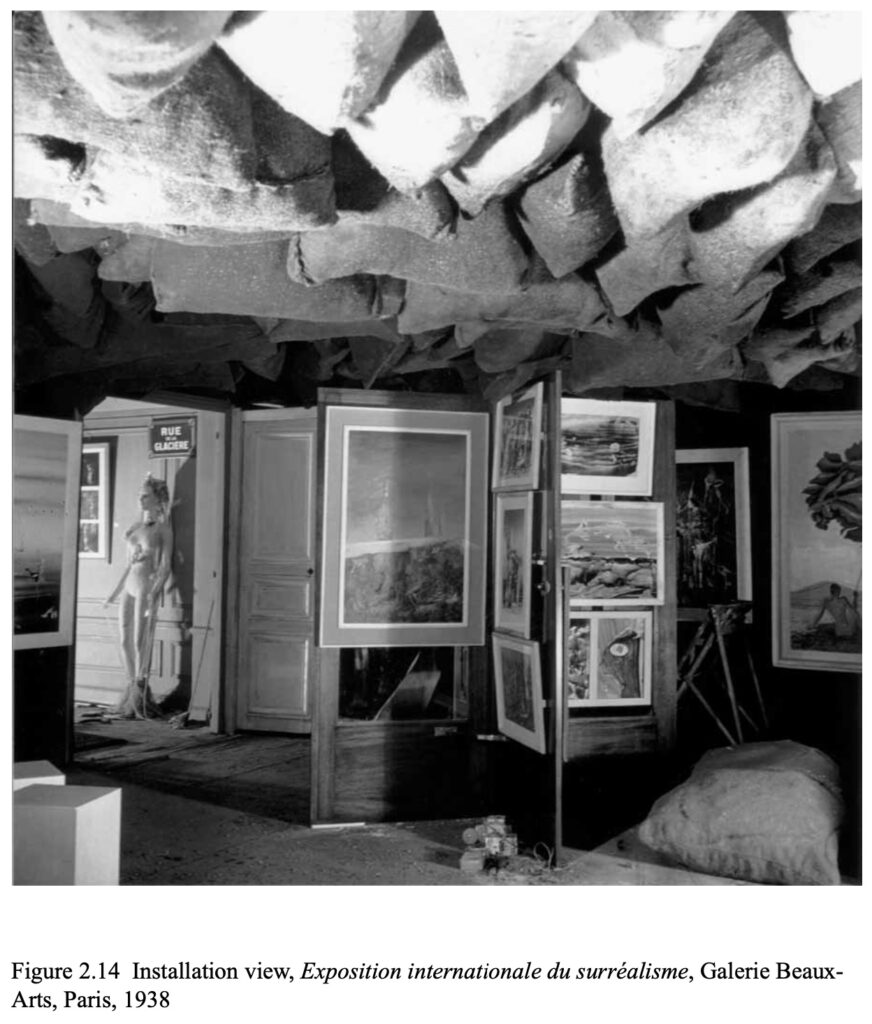

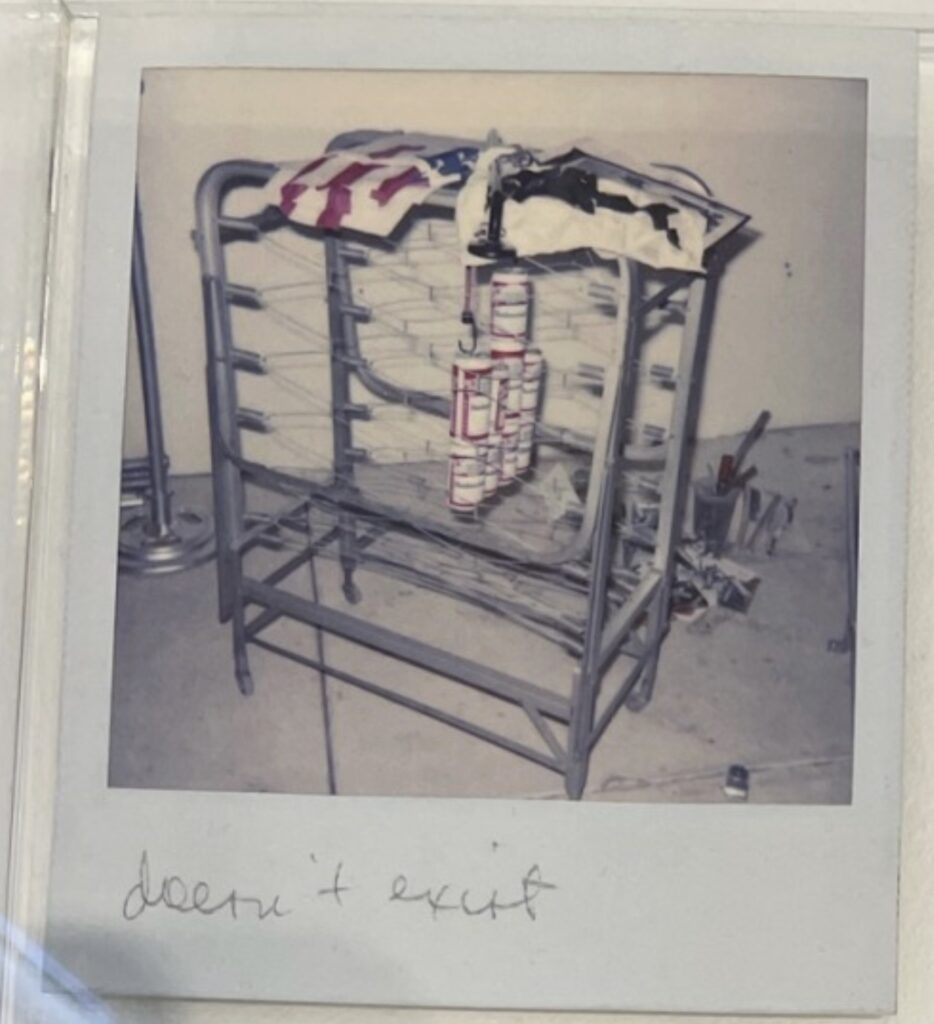

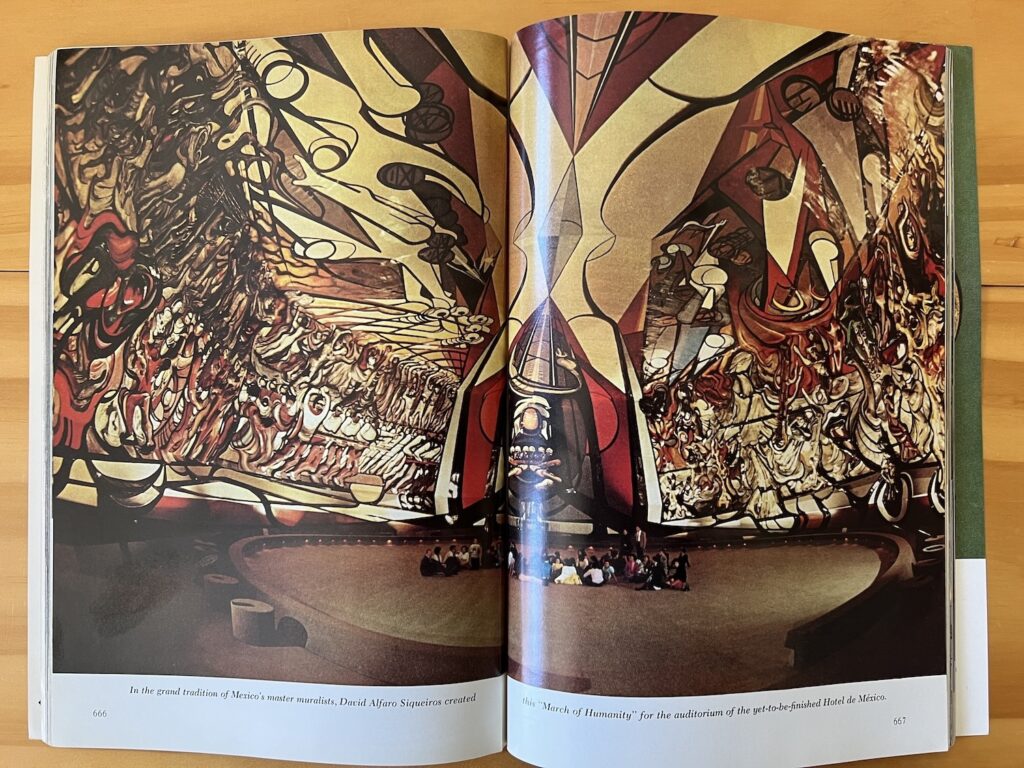

What is notable, perhaps, is that Johns chose this painting—found, vernacular, and anonymous—only after seeing this on the preceding page:

Looking on the web for contemporary images of David Alfaro Siqueiros’ absolutely gargantuan mural, la Marcha de Humanidad, in what was supposed to be the auditorium for the Hotel de Mexico, I can’t see that anyone managed to capture it more fully than Albert Moldvay did in 1973. The Mexicans sure have a national craze for murals. Jasper Johns, not so much.

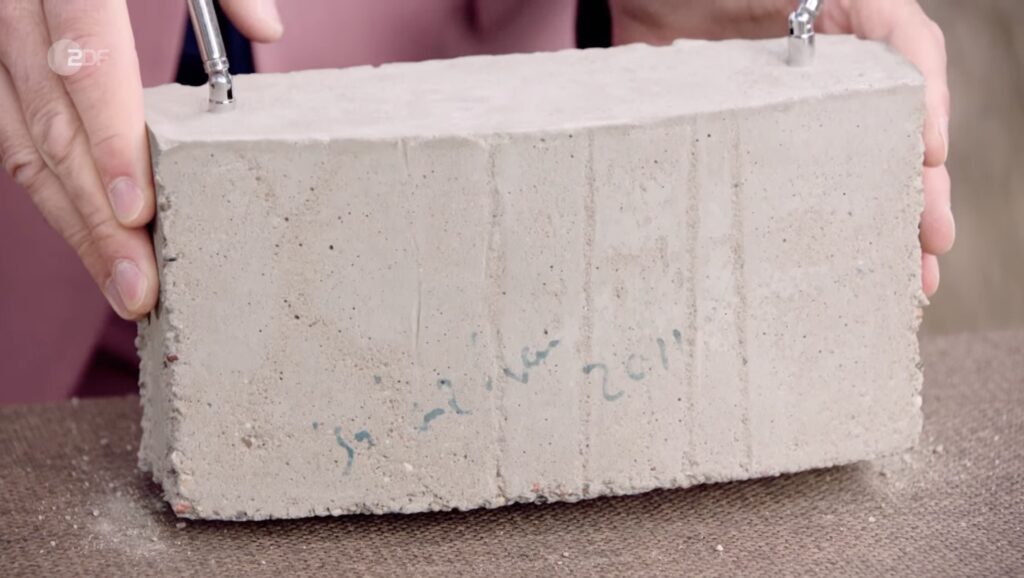

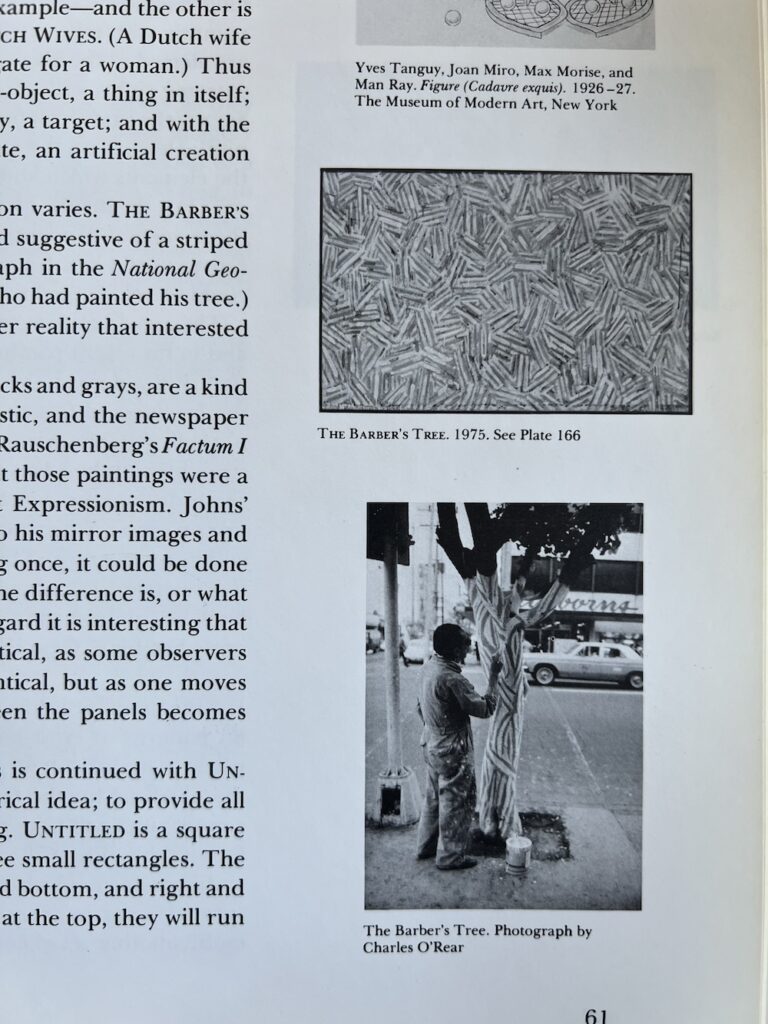

[Next morning update: Joke’s on me, it’s been on my shelf the whole time. While looking for an image of the 1975 painting The Barber’s Tree, I stumbled on it and O’Rear’s photo in Michael Crichton’s 1977 Whitney catalogue:

I’ve been saying it is barber pole-colored, but Crichton describes The Barber Tree (1975) as “flesh-and-blood colors.” Which, you’ll have to trust him, because the catalogue only had black & white images, and it was in the Ludwig’s collection until they donated it to the National Art Museum of China in 1996.

Now that they’re all together, maybe the overlapping structure of the cross-hatches is what carries through from the tree. Crichton noted Johns deployed different structures in the cross-hatch paintings of this period, 1973-76, including various degrees of mirroring or duplication. That is not what’s going on here.

Previously: Jasper Johns Drawings CR Driveby