The other day I had to laugh while watching one of the Thomas Houseago interviews Andrew Russeth posted to Gallerist NY, and the artist was talking about sculpture and time and the universe, and then he taps on his own work and goes, “in this case, bronze, which will definitely live longer than me, right? I mean, I’m gonna die much faster than that. So you have this uncanny feeling…”

Riiight. I guess Houseago hasn’t had this Guardian article open in his browser tab for the last two weeks then?

“Stolen memorials: melted down means lost for ever”

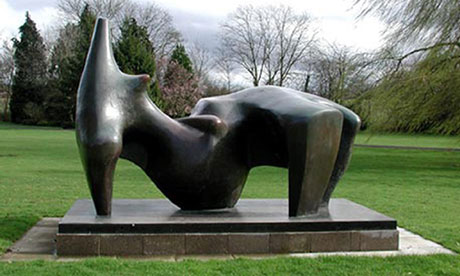

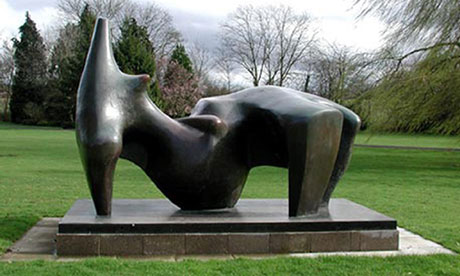

Though Sarah Bakewell’s hook is a recent uptick in the theft for scrap of bronze memorial plaques, and the loss of community and cultural memory that entails, the article is illustrated by Henry Moore’s Reclining Figure, 1969-70, (LH 608):

“This huge bronze Henry Moore sculpture, worth £3m, was stolen in 2005, chopped up and sold as scrap. Photograph: Hertfordshire Constabulary/PA”

In 2005 thieves chopped up a two-tonne sculpture by Henry Moore, managing to reduce its value from £3m to about £1,500 in scrap bronze. Yet it would seem odd to say that £2,998,500 somehow fell out of the metal and vaporised when the axes cut into it. A small part of its value does survive in images and memories of the lost work. Conversely, the attack damaged something not precisely located in the work itself: our confidence in the safety of large public sculptures.

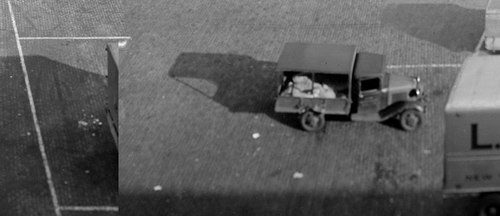

Odd indeed. And it made me wonder what had, in fact, been lost, when this sculpture we expected to exist for thousands of years, was carted off in the night on a stolen flatbed truck.

And whose fate was unknown for several years until its hacked remains were tracked to a scrap exporter in Rotterdam.

And yet whose date and title–Reclining Figure, 1969-70, LH608–the Guardian never saw fit to mention.Though accounts do report that the Henry Moore Foundation, from which it was stolen, acquired it in 1987, which, let’s come back to that.

The 3.5m-long piece had only been installed the year before (in 2004) at the Foundation’s Perry Green sculpture garden. It had been brought ‘home’ from an extended loan to the Snape Maltings concert hall in Suffolk.

In 1977, when he was nearing 80, Moore created a foundation to manage his body of work and legacy and to preserve his property in Hertfordshire. He passed away in 1986 at the age of 88, but he had taken ill and by the mid-80s, he had all but stopped working.

And yet activity at his company only intensified, with what the Foundation’s collection catalogue calls a “sudden late rush” to cast and sell everything possible while the artist was still alive:

The amount of casting during Moore’s final years was considerable, and not just of new work, since the Trustee [of the new Foundation] had become aware that many artist’s copies of sculpture made before 1977 remained uncast.

Reclining Figure LH608 was one of nine late 1986 castings of artist copies of large, pre-1977 works to move into the Foundation’s Collection.

And it’s an edition.

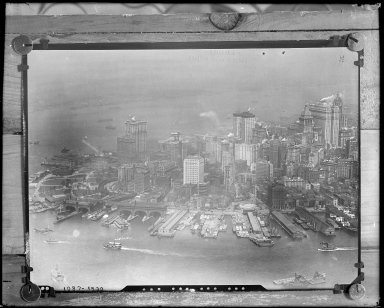

Reclining Figure LH608 in the entrance courtyard of the Louisiana Museum, image via, jaime silva’s flickr

There are other examples of LH608 in at least three public collections: at the Hakone Open-Air Museum in Japan; and at the entrances to the Louisiana Museum in Denmark [above], and the Tel Aviv Museum. And presumably, there’s a maquette somewhere, and who knows if there are other examples in whatever other sizes, in private hands. So we’ve got plenty beyond just “images and memories” to rely on

Which, I confess, though it makes it logistically easier, kind of takes the urgency out of my blindingly obvious idea: to recreate the lost Henry Moore sculpture. Which has only not been recast already because of the evolved, arbitrary constraints of the [non-Rodin] sculpture industry, which views posthumous casts differently from casts made 25 years late, while the artist was on his deathbed.

Anyway, we have the technology to bring Reclining Figure LH608 back, to rebuild her. A 3-D computer model capable of driving a CNC milling machine or a 3-D printer can readily be derived from snapshots of the sculpture. All that’s missing right now is a shot of the backside, and we can help the world’s culture recover from its hypothetically tragic £2,998,500 loss.

So, please, visitors to Denmark, Israel or Japan, send photos, so that Zombie Henry Moore Figure can recline once again.