Well those worked out rather nicely. Wrapping the star tonight. We’ll see how that goes.

Hövding Air Bag Bicycle Helmet Björk Björk Björk

I don’t know where to plot this fashion show for Hövding, the amazing, new Swedish air bag bike helmet startup, on the grid containing the Blade Runner chase scene, bike messenger tribe, post-triathlon hangout, Otakon registration, and Walter Van Bierendonck, but it’s definitely on there somewhere. [via @timoarnall]

I don’t know where to plot this fashion show for Hövding, the amazing, new Swedish air bag bike helmet startup, on the grid containing the Blade Runner chase scene, bike messenger tribe, post-triathlon hangout, Otakon registration, and Walter Van Bierendonck, but it’s definitely on there somewhere. [via @timoarnall]

Philip Glass! Philip Glass! Philip Glass!

Oh, will you look at that. Right at the epicenter of the continent’s financial crisis, Banco Sabadell, a mid-sized Spanish bank, commissioned a flash orchestra to casually assemble with their instruments in front of their closed building on the plaza and to just toss off the last, best thing the European Union’s got going for it right now, its anthem, the prelude from Ode To Joy, Beethoven’s Ninth.

That always gets me right h–oh, wait, what’s that? NPR and WQXR organized a flash choir to perform Philip Glass–and to sing a specially commissioned adaptation by the composer himself, no less–for his 75th birthday, in the center of freakin’ Times Square?

Hah, in your FACE, Europe!

Flash Choir Sings Philip Glass In Times Square [npr.org]

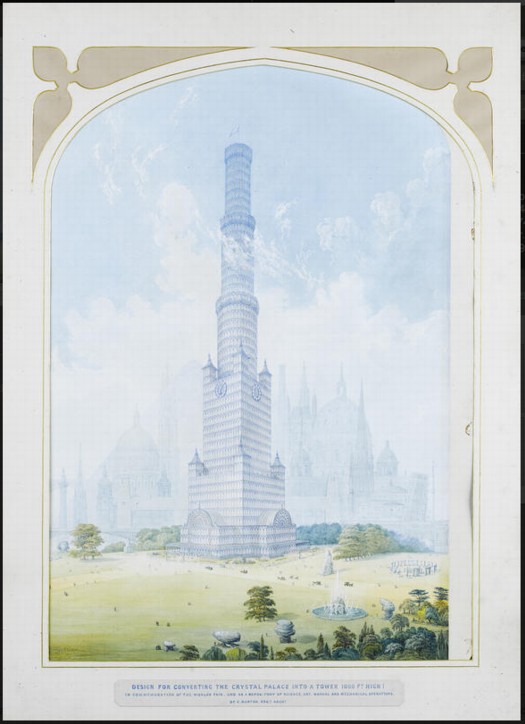

The First Skyscraper & The Second Stonehenge

Check out Charles Burton’s 1851 proposal for turning the first modern building into the first modern skyscraper:

Design for converting the Crystal Palace into a tower 1,000 ft high! in commemoration of the World’s Fair and as a repository of science, art, manual and mechanical operations.

Which is all well and good. I’ll let skyscraper historians figure that one out.

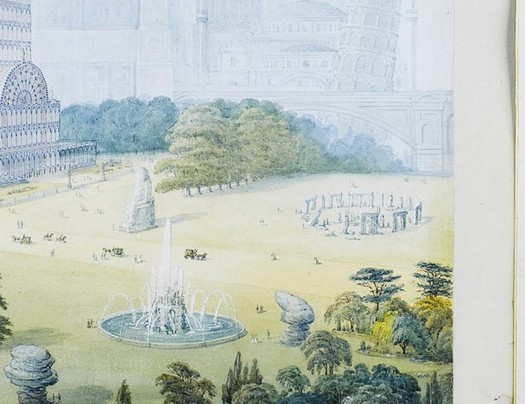

I’m wondering if there was a commonly discussed plan to install a replica of Stonehenge in Hyde Park, though, or if this, too, was Burton’s innovation.

The crazy era slips piling up in this one painting make me wonder if this was bought in 2011 by a time-traveling 1990s Verne Dawson.

Lot 171: C Burton, 19th c, sold for £6,600, 19 Jan 2011 [bonhams.com via things magazine]

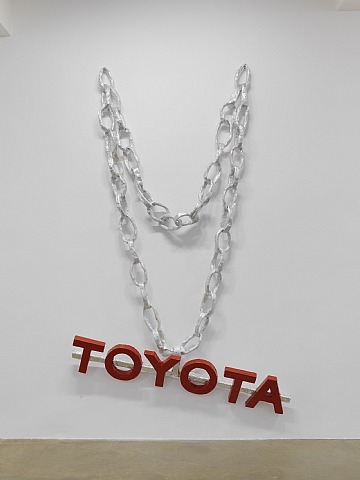

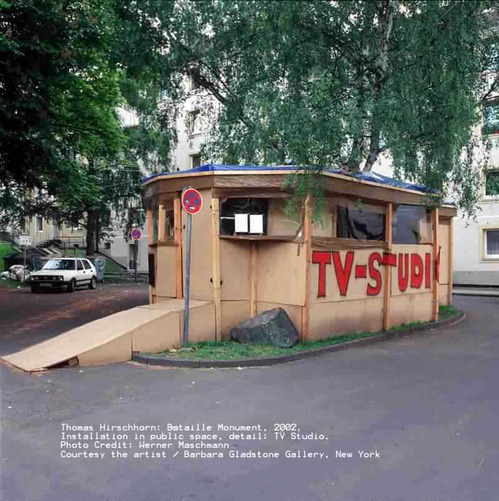

On Thomas Hirschhorn’s Chains

I fell for the first one ever saw, which was CNN, but in 2002 Thomas Hirschhorn started a whole series of gigantic, bling-inspired sculptures out of his signature, cheap-ass materials: foil, cardboard, mylar, and packing tape.

CNN was an edition of 50, published by Schellmann for Okwui Enwezor’s documenta 11, and it quickly sold out–and started getting flipped, as Pedro Velez’ artnet photo from c.2003 Art Chicago shows.

But the tricky thing is that though they were produced from the same crap as his mass edition, Hirschhorn’s other chains were unique sculptures. And that might have hurt them in the market. Phillips couldn’t sell Opel Chain (2002) for $60-80,000 in 2008, even though that was a bargain for a large-ish Hirschhorn at the time.

And though I’ll be forever grateful for introducing me to Hirschhorn’s work in the 90s, I could never ask what Chantal Crousel Galerie wanted for Toyota Chain (2002), but it was still hanging around in 2009.

I love Alison Gingeras’ quote from Parkett 57 (1999), for which Hirschhorn made an edition, Swiss Made, a giant, aluminum foil, cardboard, and packing tape watch:

Thomas Hirschhorn–an artist easily recognized for his persistent use of low-grade materials such as tinfoil, cardboard, plywood, plastic, and masking tape in his sculptural assemblages–perfectly illustrates cheapness in all of its senses. From the connotation of poor quality or shoddy standing to appearing easily made, despicable, or having little value, Hirschhorn has cultivated more than aesthetic consistency in his oeuvre. Underlying the objects that he fashions out of these meager materials is a sophisticated machine whose inner workings produce affects and interpretations that extend beyond mere formal statement. Cheap is no longer just an adjective; Hirschhorn makes it a procedure.

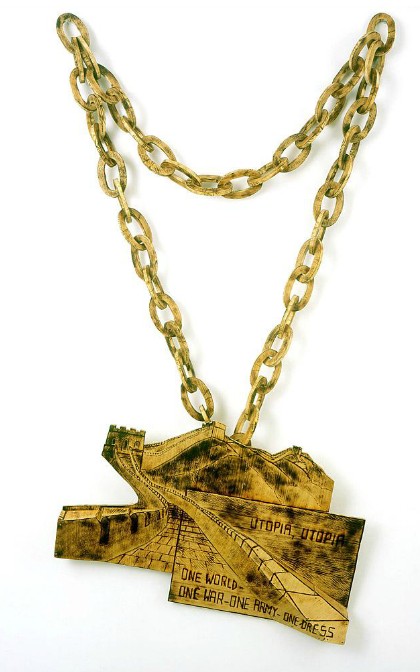

Wood Chain VII, Great Wall of China image: stephenfriedman

By 2004, Hirschhorn was making his large chain pieces out slightly more durable, more upscale wood, but I was not feeling it. I’m still not. So mylar and foam and aluminum tape it will be, simultaneously filling the Hirschhornian gap while saluting the three M’s: MOCA, Mercedes, and Mike D. Cheapness in all of its senses.

Study For Untitled (MOCA Mercedes, After Mike D), 2012

OK, people, who has not been telling me about this? In Transmission LA, the very important exhibition Mike D just curated at MOCA, sponsored by Mercedes Benz?

Fortunately, Tyler Green used flickr user Eli Carrico’s image, above, for a MOCAWTF roundup, or I might have missed it for even longer.]

Here are a couple of other views, from sadjeans, who reports that “this Mercedes emblem was six feet wide,” which, really?

And these from Nicolas Arias:

Oops, sorry, that one’s from inside the show.

Besides its own self-evident awesomeness, it reminds me of one of my favorite artworks from Documenta 11, by Thomas Hirschhorn. Hirschhorn installed his Bataille Monument in a Turkish housing complex out of Kassel’s city center.

To get to it, he’d come pick you up in a worked-over, old Mercedes, which I can’t believe I can’t find a photo of? Really, Internet? But that’s not important now.

Because the work I’m talking about his contribution to the Documenta Collection by Edition Schellmann, sold exclusively at the show. CNN is a 2.5meter-wide piece of gold chain bling with the once-relevant news network logo dangling from it. An edition of 50, the original price was just EUR1200. And when it’s come up for sale it’s been just $5,000. So it’s an awesome–and inexpensive–way to fill a wall.

Obviously, if I can’t track down this original–do we know who the artist is? Mike D? Or the edition size? Did it enter MOCA’s collection?–I will be making my own edition in the Hirschhorn-ian style to celebrate MOCA’s and Mercedes Benz’s unwavering support and incisive relevance to contemporary art.

FIVE MINUTES LATER UPDATE:

OK, then, it’s a go. Notcot has these hardhitting photos from the opening. The artist is indeed Mike D. His subversive appropriation of the Mercedes logo and his deployment of it as a readymade were not limited to the patio. He had at least two more, one leaning against a fence, and one inside, tucked into a corner.

I assume they’re from dealerships. No idea how he got a hold of them. But that does not look like six feet across; more like four. Okay, that one may be six feet. And the chains are gold[en].

Also from Notcot: this gripping firsthand report:

So it’s only natural that when curating this art festival (which they gave him carte blanche on!) he created a HUGE Mercedes emblem hanging on a large chain in the central pavillion of the exhibition… as well as a few huge emblems tucked around the space… and then around 25 special chain necklaces with authentic Mercedes-Benz emblems for the artists and key brand folks…

Which was enthusiastic enough [“Here’s Anders-Sundt Jensen, Head Of Brand Communications, modeling one of the necklaces!”] for Anders-Sundt Jensen, Head of Brand Communications, to give said necklace to said blogger at the end of the night.

Hmm, do we have a photo of Deitch wearing a Mercedes chain necklace?

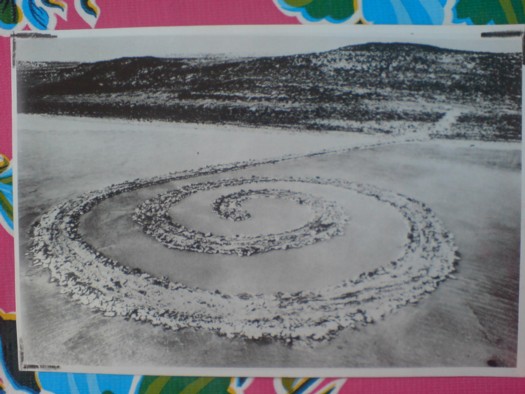

‘Jetty’

Why yes, that is what that is. A spiral “Jetty,” in fact.

New Aesthetic X Middle Earth

Nice hack. I didn’t realize James Bridle made the awesome ALL HAIL SAURON placard at the The Shard laser show; I just thought he spotted it.

Anyway, Phil Gyford thinks placards could become a platform, a way to integrate protest into the fabric of everyday life. It’d be fresher, he argues, and less invisible than bumper stickers or t-shirts.

And as much as I’d love to see Barack Obama get met in the Oval Office by someone wearing a Katharine Hamnett-style STOP THE WAR ON DRUGS or STOP FRACKING t-shirt, I think it only underscores the point that such deployments are still rely on a media to make or preserve their contextual power.

I don’t think that’s what Gyford’s suggesting, though; his placard-a-day proposal is speaking truth to power by everyone speaking truth to neighbors and people on the street.

Of course, imagine placards manage to catch on, and to survive the regulation and censorship that already befall t-shirt wearers and bumper sticker sporters, who’ve been kicked out of public [and privatized public] spaces and fired from their jobs and blurred out of reality TV shows. They’d get professionalized–in fact, they already are. The “it’s not a billboard; it’s a hapless guy with a sign!” free speech loophole is the advertising medium of choice for apartment complexes and suit outlets.

Or it used to be. Now it’s public performance art and a highly evolved sport. Last year San Diego-based Aarow Advertising held the 1st Annual World Sign Spinning Championships. The company’s founders, then 18-yo, say they invented signspinning in 2002 as a way to save themselves from what was “pretty much the worst job in the world,” standing on a busy corner holding a sign.

image via noel y.c.

As for the rest of us, how many people would communicate anything different than the message of whatever corporate brand tribe pushes their buttons correctly? Placards would become shopping bags with worse ergonomics.

Which reminds me, I just found this OG Helmut Lang shopping bag in our storage unit. I would totally carry that into every Prada store in town. STOP PATRIZIO BERTELLI.

Placads for everyday life [gyford via dan phiffer’s twitter]

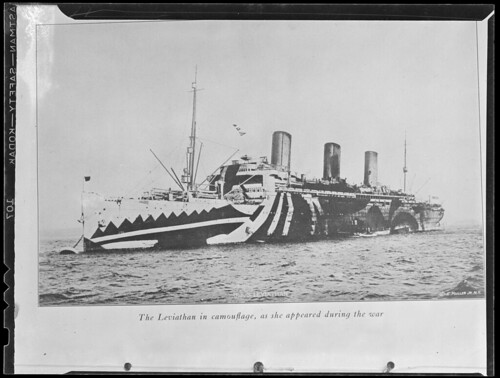

Two Ships Passing In The Night

It’s not that I feel a need to apologize for breaking some imaginary overall narrative flow, but I just need to put these here for current and future reference.

First, the SS Leviathan, as seized from Germany and as outfitted in WWI-era Dazzle Camo livery:

[boston public library’s flickr via proscriptus]

And then there’s the Lockheed Martin HALE-D, a next-generation military communications airship that obviously traces its design DNA back to the glorious Echo and PAGEOS satelloons of yesteryear. Unfortunately, like those ships, the HALE-D, and many of the inflatable, unmanned surveillance airships the Pentagon has burned $1 billion developing the last four years, have turned out to be an evolutionary dead end; the HALE-D crashed on its initial test flight, and the program is now on the chopping block.

Infrared De Kooning Drawing

First things first, yes, I’ve heard the footsteps of the Tate’s awesome, new, online exhibition/project, the Gallery Of Lost Art behind me, and I will be trying to wrap up the search for the lost Short Circuit Johns flag painting very soon. At least soon enough to give them time to write my triumphant detective work into their essay. Ahem.

Meanwhile, let’s give credit where it’s due, because the Tatefolk have lured SFMOMA’s infrared imagery of Erased de Kooning Drawing out and onto the net.

Last year at CAA, one of SFMOMA’s design & web people Chad Coerver talked about the debates over whether or how to present the wealth of information in the Museum’s Getty-sponsored Rauschenberg Research Project. Whether to publish new infrared imagery of EdKD, for example, which might alter the way people perceive the object in ways the artist did not want or anticipate.

I guess they figured it out, because not only does the GOLA have it, the IR image is the teaser today on SFMOMA’s tumblr. [via wiblog and MAN]

Or maybe they’re still working on it. SFMOMA’s Erased De Kooning Drawing page has this footnote:

The use of advanced imaging technology and its implications for our understanding of Erased de Kooning Drawing will be explored fully through SFMOMA’s Rauschenberg Research Project, a four-year in-depth research program that will result in an online catalogue, slated for launch in summer 2013.

Carry on, then!

But the page also has this description, which seems to reflect a fuller, and different, understanding of the work than what was discussed during Rauschenberg’s lifetime:

After Rauschenberg completed the laborious erasure, he and fellow artist Jasper Johns devised a scheme for labeling, matting, and framing the work, with Johns inscribing the following words below the now-obliterated de Kooning drawing:

ERASED DE KOONING DRAWING

ROBERT RAUSCHENBERG

1953

The simple, gilded frame and understated inscription are integral parts of the finished artwork. Without the inscription, one would have no idea what is in the frame; the piece would be indecipherable. Together the erased page, inscription, and frame stand as evidence of the psychologically loaded deed of rendering another’s artwork invisible, enacted in the privacy of the artist’s studio.

Which, hmm. It seems vital that Johns’s central role in creating EdKD is acknowledged. I’d even argue it was equal, or equivalent, his precisely drawn marks the precise counterweight to Rauschenberg’s vigorous erasures. And the title, even the titling, and thus the conceptual framing, is Johns.

Or at least it was. But the gilt and the current matting, has been changed, once and maybe twice or more, since Johns and Rauschenberg broke up. So it is Bob’s. And the evidence of this evolution can be seen even more clearly, thanks to the Gallery of Lost Art’s zooming feature, on the back of the work.

RIP, Ivan Karp, And Thanks

I’ll get back to the Rauschenberg thing in a bit, but it’s already been too long that I haven’t noted the passing of Ivan Karp. He had been an amazingly generous, interesting, and informative resource to me over the years I’ve been delving into the history of postwar art, always ready to share a story, or an opinion, a recollection, or a corrective. And I’m sad to think we won’t be having any more chats. My thoughts are with his family, and especially his wife, the artist and historian Marilynn Gelfman Karp, who has also been very thoughtful and generous with her insights and stories.

An anecdote in Ivan’s NY Times obituary about how he and Marilynn met in what became an epicenter of the 1960s New York art world reminded me of a better version, from Ivan’s 1969 oral history interview for the Archives of American Art:

So kind of unknowingly the gallery by being what it was, an outgoing open place became a center of activity. People come in here and spend a lot of time. They’d meet each other. Every Saturday was an important event at the gallery. Dozens of people standing around in the back room discovering each other. There was a lot of romantic atmosphere. Always a lot of beautiful girls there. What always made the gallery activity worthwhile for me was the number of beautiful people and especially the beautiful girls who always came in. They were always particularly welcome; as they are to day still. That’s where I met my wife — at the gallery. She brought in slides and, in fact, brought in some paintings of an artist she was interested in. And I guess I was more interested in her than I was in the painter. But I think we did show the artist. And then I married his sponsor.

This painter was Vern Blosum. When I met Blosum almost 50 years later, it was clear he remembered the sting of losing his girlfriend as if it was yesterday.

For his part, when I called Ivan several years ago out of the blue and told him I wanted to talk with him about Vern Blosum, he just laughed and laughed. The jig was finally up.

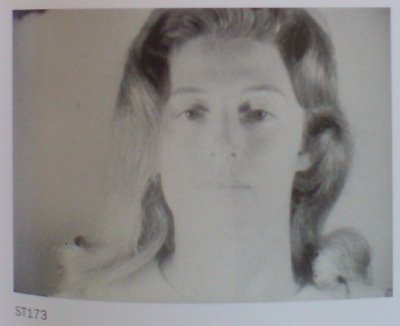

images: Ivan and Marilynn Karp from their Screen Tests, ST171 and ST173, both 1964, obviously ganked from Callie Angell’s Warhol Screen Tests Catalogue Raisonne. Marilynn was also filmed for Warhol’s The Thirteen Most Beautiful Women.

Beebe v. Rauschenberg: Declaring ‘Victory’

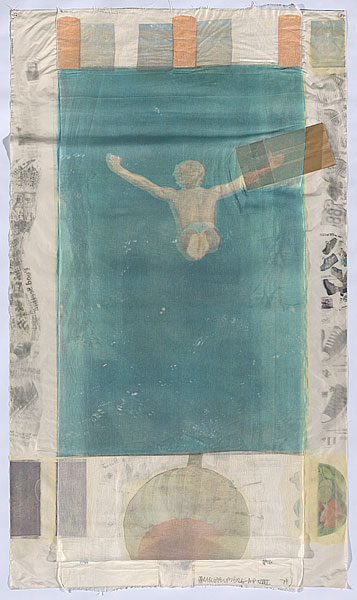

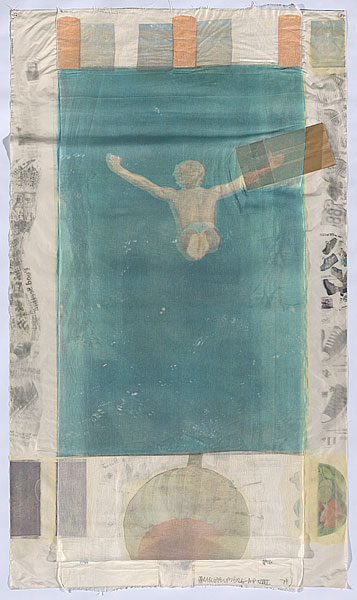

One of the first and only reports I could find that discussed San Francisco photographer Morton Beebe’s pioneering 1979 copyright infringement lawsuit against Robert Rauschenberg is Gay Morris’s Jan. 1981 article on photo appropriation in ArtNEWS. The title pretty much says it all: “When Artists Use Photographs: Is it fair use, legitimate transformation, or rip-off?” [excerpt here.]

Beebe and Rauschenberg settled before the case really got rolling–for $3,000; a copy of Pull, the Hoarfrost Edition that included a two-layer, screenprinted version of Beebe’s “Diver” image; and a promise of a good faith effort on the part of Gemini and Rauschenberg to include a photo credit for Beebe whenever Pull was exhibited or published. [The extent of Gemini’s subsequent ability and/or effort to secure such credit from institutions can be seen in the print studio’s own catalogue raisonne at the National Gallery of Art. Where there’s no mention of Beebe.]

When I first called him a few weeks ago, Beebe told me what he told Morris, even though the settlement was paltry, and his lawyer got basically all of it [including, if I understand correctly, Beebe’s initial copy of Pull]: I consider it a victory for myself and for photographers.” [update: nope, according to his website Beebe kept his copy of Pull and only sold it in 2004, along with his correspondence, and a print of his original photo.]

Rauschenberg’s and Gemini’s lawyer, Irwin Spiegel, meanwhile, continued to assert the right of artists “working in the medium of collage…to make fair use of prior printed and published materials in the creation” of their original artwork.

Though he opens with Beebe v Rauschenberg, which may be the first actual lawsuit filed against an artist for using a photograph, Morris’s ArtNEWS article covers a lot of photographic territory. It conflates the use of photographs by artists to make paintings or prints–like Warhol’s use of Patricia Caulfield’s flowers photo, taken from a magazine, or Larry Rivers’ drawing based on Arnold Newman’s portrait of Picasso–with companies using photos in fabric patterns and in publications without permission or payment. Which seem like completely different scenarios, though it’s not like the copyright world reflects that, even 30 years later. It’s still “a legal issue,” as Caulfield said in 1981, “because there’s a moral one.”

photo of hibiscus flowers by Modern Photography executive editor Patricia Caulfield, published in that magazine in 1964 where it was found and used by Andy Warhol

What bugged Caulfield, she said, was the way using an image without recognition or permission “denigrate[s] the original talent.” [Definitely read Martha Buskirk’s account of Caufield’s sexist denigration at the hands of Team Warhol in her great 2003 book, The Contingent Object of Contemporary Art.] For Newman, it’s the way these artists “think it’s just a photograph” without considering that there is a person behind the photograph, as Morris writes, “just as there is a person behind a painting.” Beebe’s complaint, too, was primarily one of “recognition.”

And undeserved anonymity never hurt so bad as when you have to find out about it in Robert Hughes’ Time cover story that the World’s Most Famous Artist’s latest , greatest masterpiece was basically your uncredited photo:

But the delicacy of his touch produced its masterpiece in the Hoarfrost series he did with Gemini in 1974. The Hoarfrosts are sheets of silk, chiffon, taffeta, one hung over another. Each sheet is imprinted with images from Rauschenberg’s bank. In Pull, 1974, the dominant one is of a diver vanishing into a pool, seen from above, swallowed in blue immensity like a man on a space walk. No reproduction can attest to the subtlety of its play between the documentary “reality” of collage and the vague beauties of atmosphere.

And that comes just a few paragraphs after Hughes praised Bob’s amazing aversion to fame and his generous love of collaboration, even at his own expense. [“Dozens of people ripped Bob off for money and time,” a friend from the ’60s recalls, “and he knew it, but he never said a word against them.”]

I mention all of this, partly because it still sounds so familiar: the indignation of wronged photographers. The artists defending their innocent intent, freedom of expression and transformative practices. The vast disparities in celebrity, critical response, and economic value between the sourcer and the sourced. The near-universal frustration with the expense and hassle of the court system, which almost always culminates in a privately negotiated, not litigated, settlement.

Beebe told Morris that he settled rather than “risk losing the case on ‘a technicality.'” He told me that Rauschenberg, whose LA-based lawyer had argued to have the case dismissed or moved out of [Beebe’s hometown] San Francisco because of the onerous burden of traveling there, caved rather than go through a deposition. [Which, given Richard Prince’s fraught experience being deposed, is understandable.] Though Beebe also touted the judge’s sympathetic-bordering-on-slamdunk statements to me, I think he recognized that the settlement was the best deal he was gonna get.

I’ve obtained and reviewed the court documents in Beebe v. Rauschenberg. In the case’s one court hearing, held on June 13, 1980, Judge Robert H. Schnacke scoffed at Spiegel’s assertion that just being “an artist of international repute” didn’t mean that Rauschenberg fell under the Bay Area court’s jurisdiction, and anyway, Los Angeles was far easier for his client to reach. And he repeatedly voiced skepticism toward what he called, “copying”:

THE COURT: I’m a little concerned that an artist of international repute finds it necessary to copy photographs into his finished product. I appreciate that I’m not current on all present modes of art, but I thought there was a distinction between copying and artistry.

MR. SPIEGEL: Well, certainly, but that gets into the merits of the case and when we get to the merits–

THE COURT: Apparently the international repute of the artist in some way was relevant to our argument. I was just wondering if [his] international reputation was built upon the fact that he copied other people’s work.

Nevertheless, Judge Schnacke ruled that Beebe would need to front Rauschenberg’s travel expenses to San Francisco for a deposition. Which might have had some impact on Beebe’s priorities as well.

I think I’ll do at least one more post that looks at the way the conflict unfolded–the timeline feels nontrivial to understanding the case itself–and to looking into the “technicalities” of Beebe’s image, where it ran, and how Rauschenberg & Gemini used it. And I’ll probably scan and post at least some of the key court documents, especially Beebe’s complaint and Gemini’s rather extensive information requests and affirmative response.

Meanwhile, to start, I’ve transcribed the first letters of exchange between Beebe and Rauschenberg, which were precipitated, Beebe said, by Christo & Jeanne-Claude recognizing Beebe’s “Diver” from Time Magazine. It all sounded so amenable and promising.

Continue reading “Beebe v. Rauschenberg: Declaring ‘Victory’”

Beebe v. Rauschenberg, The First Big Appropriation Lawsuit

I’ve been annoyed for six weeks now by Laura Gilbert’s op-ed in The Art Newspaper which argues, rather speciously, that “‘appropriation'” [her scare quotes] is somehow a less “savvy” artistic practice than licensing images or seeking permission. She frames this as somehow “rarely reported,” as if there’s a taboo in the art world about acknowledging that some highly successful artists who have been accused of copyright infringement find the process annoying and expensive, and thus seek to avoid it going forward. This is certainly true, but such burdens could just as easily be used to argue, as some TAN commenters have, that the copyright litigation system is unwieldy and favors the big and powerful. [The examples of happy happy licensing Gilbert cites–Koons & Marvel; Warhol & Disney–support this.]

But whatever, I decided way back when the Cariou v. Prince complaint surfaced that I wasn’t going to go tit for tat on every column or blog post concern trolling about copyright infringement.

Rauschenberg’s Pull (Hoarfrost Series), 1974, 8×4 feet, offset and silkscreen

on fabric, silk, and cheesecloth collage and paper bags, ed. 29 plus a bunch of proofs, image: nga.gov.au

What I will do, though, is confess that for all the soaking I’ve been doing in appropriation, I had never heard of the case Gilbert discussed at the greatest length: when Robert Rauschenberg was sued for using an image from a magazine ad in one of his collages by the photographer who took it, Morton Beebe.

San Francisco photographer Morton Beebe only discovered that Robert Rauschenberg had used two of his photographs in the 1974 print Pull when his friends, artists Christo and Jean-Claude, were looking at his portfolio. Christo pointed to the photograph Mexico Diver and said: “My God, is that yours or Rauschenberg’s? Have you seen Time magazine this week?”

Beebe got hold of the magazine and saw in a feature about Rauschenberg that he had not only used Mexico Diver but also his photograph of a native New Guinean repeated across the top of the print. Both pictures were part of a series Beebe had shot for an advertisement for Nikon cameras that had appeared in 17 magazines.

Beebe sued. Rauschenberg’s printer testified that the artist had showed him the Nikon ad and said: “I’ll just lift it.”

Rauschenberg settled, paid the photographer’s legal fees and gave him a numbered print of Pull. He promised that whenever the image appeared in print Beebe would be acknowledged. Later, when Beebe discovered another unauthorised use of Mexico Diver, Rauschenberg gave him another print of Pull, which Beebe sold for $13,000.

Beebe points out that potentially high legal fees makes photographers reluctant to sue (in the US litigants typically bear their own costs). After the suit settled, in 1980, Rauschenberg shifted to using his own photographs exclusively for the next 28 years if his life, according to the Guggenheim Museum and others.

I am quoting Gilbert’s entire account of the case here because it sounds quite compelling and authoritative. But it is also biased–it’s based entirely on Beebe’s version of the claim and the settlement. And after investigating the original court documents, it’s clear that Beebe’s take leaves out key details and facts that could significantly affect how the case is perceived, and what it means.

There’s no doubt that Rauschenberg used Beebe’s image without permission, nor is there any uncertainty that Beebe felt wronged by the far more famous artist’s action. It’s also the case that Rauschenberg insisted, even after settling with Beebe, that his collage process was fair use, and that it resulted in entirely new work. If for no other reason, Beebe v. Rauschenberg should be better known because it embodies these emotional, economic, and power complexities so concisely.

Ultimately, though, I think the case does not support the anti-appropriation position that Beebe and Gilbert are promoting. [As recently as 2010, Beebe used his Rauschenberg complaint to lobby the White House (pdf) to strengthen IP laws “to better protect the creative community from piracy even from our fellow artists.”] I’ll get to that in the next post[s].

The other thing that’s amazing and feels important about Beebe v. Rauschenberg is the similarity–which Gilbert surely caught onto as well–between Rauschenberg’s appropriations and Prince’s. I mean, seriously, people, Rauschenberg had made Pull from a Nikon ad in 1974, three years before Richard Prince rephotographed his first magazine ad at all–and six years before he rephotographed his first Marlboro cowboys. And while Prince was working in the bowels of Time Magazine making tear sheets, Rauschenberg was designing his own Time cover–and putting a little registered copyright symbol in the corner.

No Longer Appropriate? by Laura Gilbert [theartnewspaper]

One of the few articles to discuss Beebe v. Rauschenberg, Gay Morris’s 1981 Artnet article, “When Artists Use Photographs: Is it fair use, legitimate transformation, or rip off?”, is excerpted in the 2007 textbook, Law, Ethics, & The Visual Arts

Or Did Just Everyone Have A VW Bus And A Loft Back Then?

Seriously, people, maybe I should just start documenting the artists and avant garde music folks in the 1960s who didn’t roam around in a VW Bus. Here is composer Terry Riley, published in William Duckworth’s 1999 interview collection, Talking Music:

DUCKWORTH: When did you move to New York?

RILEY: I came to New York in 1965. After the In C performances, I went to Mexico on a bus for three months. I was actually looking for something, but I didn’t know what. I guess after In C, I was a little bit wondering what the next step was to be, you know. And I guess what I really wanted to do was go back and live in Morocco, because I was interested in Eastern music, and at that time, Moroccan music attracted me the most. I had lived there in the early sixties. In 1961, I went to Morocco and was really impressed with Arabic music. So we went to Mexico. My point was to get to Vera Cruz, put our Volkswagen bus on a boat and have it shipped to Tangier, and live in Morocco on the bus. We drove all the way down to Vera Cruz, but couldn’t get a boat; nobody would put our bus on the boat. So we drove all the way up to New York. We were going to try to do the same thing from New York, right? But I started hanging out with La Monte [Young] again and renewing old acquaintances. And Walter De Maria, who was a sculptor, had a friend who was leaving his apartment. THis guy had a fantastic loft on Grand Street. And he said, “Do you want to trade the loft for the bus?” So I did, and that began my four-year stay in New York.

Riley also had a wife and small kid at the time, and she supported the family by substitute teaching along their nomadic journeys. Amazing.

Previously: Walter de Maria’s stainless steel sculptures, including a musical instrument for La Monte Young, produced in 1965

The VW Years, Appendix: Living Theatre

Welcome to another episode of The VW Years, greg.org’s ongoing mission to seek out firsthand accounts of John Cage and Merce Cunningham’s VW Bus.

These are some mentions of John Cage in The Living Theatre: Art, Exile, and Outrage,, John Tytell’s 1995 history/biography of Living Theatre founders Judith Malina and Julian Beck, which were compiled by Josh Ronsen and posted to silence-digest, a Cage-related mailing list in 1998:

“At the end of September, they visited Cage and Cunningham who had expressed an interest in sharing a place that could be used for concerts and dance recitals. Gracious, unassuming, the two men lived in a large white room, bare except for matting, a marble slab on the floor for a table, and long strips of foam rubber on the walls for seating. The environment reflected their minimalist aesthetic. Cage proposed to stage a piece by Satie that consisted of 840 repetitions of a one-minute composition. He advised them not to rely on newspaper advertising, but to use instead men with placards on tall stilts and others with drums.” –pg 72

…

“the only person Judith admitted caring about was John Cage, “mad and unquenchable” with his “hearty, heartless grin.” With Julian, she visited Cage in Stoney Point in the Hudson Valley. … Julian thought Cage was the “chain breaker among the shackled who love the sound of their chains.” Cage collected wild mushrooms, which Julian interpreted as a tribute to his reliance on chance as much as to his exquisite taste. … [Paul] Williams wanted to help them find a new location that Cage and Cunningham could share with The Living Theatre.” -pg 121

“In the middle of 1957, they saw Cunningham dance at the Brooklyn Academy of Music to Cage’s music. At a party afterward, C&C laughed all night like “two mischievous kids who had succeeded in some tremendous boyish escapade.”” -pg 125

“[they] visited Cage in Stoney Point, where they made strawberry jam and gathered mint, wild watercress, and asparagus for dinner. Feeling a surge of confidence in his own writing, he [Julian] gave Cage a group of poems to set to music.” -pg 128

“With Judith, Julian, Cunningham, and Paul Williams, John Cage drove from “columned loft to aerie garage” in his Volkswagen bus, smiling despite the traffic and the fact that their search was now in its 4th month. Finally, they found an abandoned building, formally a department store on 14th st and 6th ave, which Williams declare would be suitable for sharing as a theatre and dance space.” – pg 129

“Early in December, with Cage’s assistance, [Cunningham] moved some of his backdrops into the space. Cage brought with him a variety of percussion instruments–he owned more than 300 at that time–which he donated to the theatre. Julian thought there was a distance about Cage that prevented intimacy and the fullest communication, but he felt Cage’s gift was a real sign of the artistic support that would be crucial to the success of The Living Theatre.” -pg 140