So beautiful. Or is it elegant?

Either way, the degraded, abstracted pixelation of user canzona‘s 1000th ripped & uploaded YouTube video is a great digital tribute to experimental composer Alvin Lucier and the ‘photocopy effect,’ “where upon repeated copies the object begin to accumulate the idiosyncrasies of the medium doing the copying.”

As MeFite DU puts it, “I like how it’s called ‘the photocopy effect,’ but was inspired by a sound recording.”

I Am Sitting In A Video Room 1000 [youtube via @joygarnett]

Pour Copie Conforme

After bagging on Blake Gopnik’s comments on Marcel Duchamp playing the buyers of his readymades for fools, I started looking more closely at Duchamp’s actual statements and working process. It’s so easy to consider him as just a source of ideas, and to forget that in fact, he expended a great deal of effort and time on the creation of objects.

On the other hand, that dude would sign just about anything that wasn’t nailed down. Including readymades that were really made, or found, or bought, by others. All over the place. The only thing that stopped him, it seems, was Arturo Schwartz, who insisted Duchamp stop signing stuff to protect the value of the 1964 readymade editions.

One example: when the late photographer, painter, and avant garde filmmaker Dennis Hopper met Duchamp on the day of the opening of his 1963 retrospective in Pasadena, he grabbed a sign from the Hotel Green, where Duchamp was staying, and asked him to sign it. And he totally did.

Another, from Francis Naumann’s incredible practice history, Marcel Duchamp: The Art of Making Art In The Age Of Mechanical Reproduction, which I picked up at the suggestion of John Powers [Naumann’s gallery was the site of that fantastic Duchamp chess show last year.]:

During the time of the Pasadena exhibition, Duchamp was invited to attend a breakfast in his honor at the home of Betty Asher, an important collector of contemporary art who lived in West Los Angeles. Among the thirty or more guests she invited, one of them, Irving Blum, then owner of the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles, asked Duchamp if he would consider signing a bottle rack he had found and purchased from a local thrift shop. Just in case the artist agreed, Blum brought the item along with him to the breakfast. When Blum asked, Duchamp responded: “Gladly,” whereupon Blum retrieved the work from the trunk of his car and Duchamp signed it on the bottom rung, adding the usual inscription, “pour copie conforme,” and the date: “1963-14”. When Blum was in the process of returning this treasured artifact to the trunk of his car, Richard Hamilton reportedly rushed out of the Asher house and quipped: “You are, of course, aware of the fact, Mr. Blum, that in order to devalue his work, Duchamp signs everything.” [p.235, emphasis added for the awesome parts]

Indeed, and one of the last things he signed was the replica of Bicycle Wheel which Hamilton had made, and had asked Duchamp to sign the next time he passed through London. [Blum donated his Bottle Rack, below, to the Norton Simon Museum in 1968 after Duchamp’s death.]

And Pontus Hulten told how Duchamp said the Modernamuseet could save money by making a bunch of readymade replicas for a show instead of shipping them: “Duchamp later signed everything. He loved the idea that an artwork could be repeated. He hated ‘original’ artworks with prices to match.” [p.213]

Which is making me nod and laugh out loud right now as I sit here, with a pile of pens, signing my name over and over and over on the stack of certificates for the edition I’m doing with 20×200.com, which is going to be announced very soon. Stay tuned.

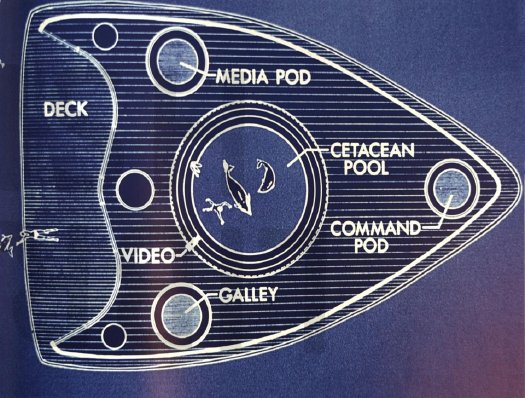

Cue The Dolphin Embassy

The architecture and art collective Ant Farm first proposed The Dolphin Embassy in Esquire magazine in 1974. When they ended up meeting the owner of the Dolphinarium in Australia a couple of years later, they worked it up into a full-fledged proposal, which got funding from the Rockefeller Foundation and a show at SFMOMA.

Basically, the idea morphed from an underwater building into an open, mobile laboratory craft [above] to facilitate human-dolphin interaction in the wild. [spatial agency has images of both early designs.] First, they would deploy the awesome power of video technology to create a common language with the dolphins. Then…

Here’s Ant Farmer Doug Michels talking about the project with Connie Lewallen in the catalogue for the 2004 retrospective at Berkeley Art Museum:

The next year and a half for me [from 1977-8] was filled with trying to make the Dolphin Embassy real. There was a lot of time spent with both captive and wild dolphins and researching dolphins, a lot of design time on the boat, and a lot of public relations time communicating the dolphin idea to Australia. Putting it in historical context, we were feeling pretty confident about accomplishing things. The House of the Century had been built, Media Burn had been done, The Eternal Frame–these large-scale productions. Cracking the dolphin communication code, well, how hard could that be?! (Laughs.)

CONNIE: Why didn’t the Dolphin Embassy get built?

DOUG: Eventually, it became clear that it was a gigantic project beyond the scale we could accomplish with the funds we had raised. While we didn’t solve cetacean communication during our mission in Australia, the Dolphin Embassy experience provided a deeper view into the mysteries of Delphic civilization.

A few months ago Andrea Grover posted this great 1976 photo of a TV-toting Michels having a diplomatic summit of some kind with his dolphin counterpart. Not sure what they discussed.

From the disbanding of Ant Farm in 1977 up until his unexpected death in 2003, Michels kept developing the Dolphin Embassy concept. By 1987, it was retitled Bluestar, a joint dolphin-human-compatible space colony with a 250-ft diameter sphere of water “ultrasonically stabilized” within a wall of space-made glass. My merely 100-ft satelloon bows in awe at the thought.

Anyway, I’m reminded of all this now because, with the iPad and all, it may be time to dust off those Dolphin Embassy blueprints.

Speak Dolphin press release at Orange Crate Art [mleddy via boingboing]

Doug Michels, Dolphin Lover [andreagrover.com]

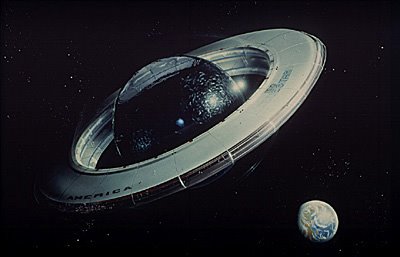

Orbit: Final Conflict

Took me a couple of months, but I finally figured out which, out-of-place alien Washington embassy in the short-lived, suspiciously-generous-aliens-move-into-Earth TV series Anish Kapoor’s wacked out Orbit Tower reminded me of: the one in Gene Roddenberry’s Earth: Final Conflict.

Glad to have that off my plate.

Into Orbit [kosmograd via things]

[images via willwiles and rivenwolf]

The Greatest Camo Story Ever Told

Sure, there’s Dutch Camo Landscapes, and Razzle Dazzle, and the Civilian Camouflage Council, but it all pales in comparison to the truly epic WWII camo accomplishments of Jasper Maskelyne and The Magic Gang.

Sure, there’s Dutch Camo Landscapes, and Razzle Dazzle, and the Civilian Camouflage Council, but it all pales in comparison to the truly epic WWII camo accomplishments of Jasper Maskelyne and The Magic Gang.

Maskelyne was a British magician-turned-Army camo mastermind who, in 1941, led a ragtag band of desert artists and illusionists who created a series of incredible camo techniques that protected Allied forces in North Africa from aerial reconnaissance and bombardment.

Using burlap and sticks, they disguised trucks as tanks, and tanks as trucks, and they created devices to enable tanks to cover their own tracks across the desert sands. But the most amazing achievements are in his 1949 memoirs, Magic – Top Secret where Maskelyne–whose grandfather, also a magician, invented the pay toilet–tells how he saved the port of Alexandria, Egypt from night bombing by building an elaborately lit decoy port, several miles away in the desert. Using incendiary devices and real anti-aircraft artillery, he and his Magic Gang fooled the German bombers with realistic-looking “hits” and return fire; and by morning, his crews would strew papier-mache rubble around the real port, giving simulated damage for the reconn pilots to report back. [below: a German spy photo of part of the port]

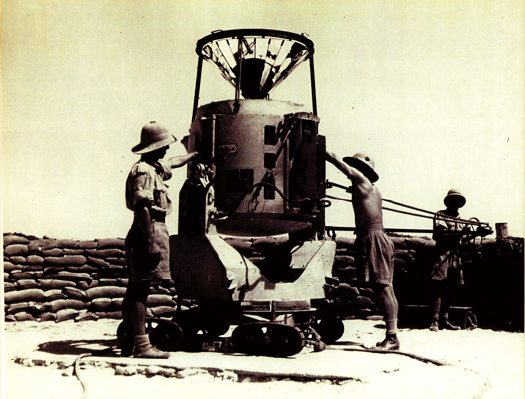

The success of the Alexandria decoy was only surpassed by Maskelyne’s brilliant [literally] strategy for protecting a vital supply route for the Allies, the Suez Canal. He designed “Dazzle Lights,” a rotating structure of made up of mirrors and 24 powerful anti-aircraft searchlights that, when set into motion, gave off a “Whirling Spray,”:

[Maskelyne] managed to create beams nine miles long, twenty-four of them from each searchlights [sic] … the magic mirrors were a success, and the next job was to get the device into mass production. With them, we made twenty-one searchlights serve for the entire one-hundred-mile length of the Suez Canal.

That’s right, the Suez Canal was saved from being bombed by the biggest lightshow in history: the 100-mile-long, Whirling Spray of almost two dozen Dazzle Lights.

How is it possible that I did not know this before now? Why is this miracle of modern warfare not taught in our military academies? Our elementary schools, even? How are these mindblowing aesthetic achievements not celebrated as a landmark in the history of art? Why is there no Bruckheimer movie, starring Josh Hartnett as the daring soldier magician? Maybe because the entire thing is bullshit.

In 2004, military historian and magician [seriously] Richard Stokes published the findings of his multi-year investigation into Maskelyne’s claims. They are gathered in the exhaustively paged website, MaskelyneMagic.com. Working with the magician’s son, he had access to Maskelyne’s archives and scrapbooks from the war. Stokes also cross-referenced official records, declassified intelligence reports, and consulted experts and historians in the North African war. And there is nothing in the historical record to support Maskelyne’s fantastical claims.

On Alexandria, the place where he said he built a decoy port doesn’t even exist; neither does the geography he describe match to any in the vicinity of the city. There are no pictures or corroborating eyewitness accounts, and no documentation.

On the Suez front, Stokes demolishes Maskelyne’s claim to have invented Dazzle Lights by pointing to similar, tank-based tactics under development since WWI. Again, no record of Dazzle Lights can be found in the historical source material, and extensive accounts of the actual defense of the Canal provide well-documented alternative explanations to Maskelyne’s. According to Stokes, Maskelyne didn’t actually come up with the Whirling Spray idea until 1942, after the aerial threat had subsided. And he quotes the illusionist’s son: “The ‘Dazzle Lights’ were an idea which was, I believe, constructed only in one prototype and tested on one occasion.”

Which appears to be the scene depicted in the photo gallery on Stokes’ site, where a searchlight is being outfitted with a faceted, mirrored cone extension:

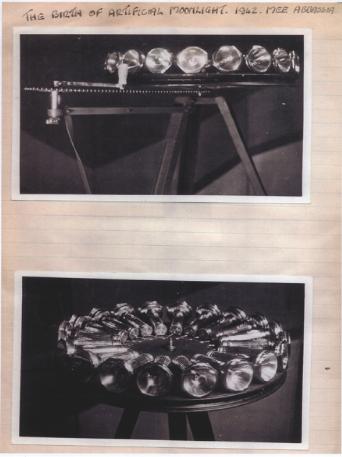

Which means the photo below, showing an awesomely Duchampian folly, 18 flashlights on a turntable, is somewhat confusing to me:

But with a caption like, “The birth of artificial moonlight, 1942,” I’d think that Maskelyne’s imagined heroics are long overdue for [re-]creation.

The War Magician| “”Myth is invulnerable to mere facts” – Barthes [all images via MaskelyneMagic.com]

Previously: Bombardment Periphery, Rotterdam, and Los Angeles’s ‘wigwam’ of searchlights; Forrest Myers’ light pyramid

Tomasons And Akasegawa Genpei, Translated

I’ve got browser tabs full of sweet, sweet updates and extensions to some earlier posts. I’ll start with Tomasons.

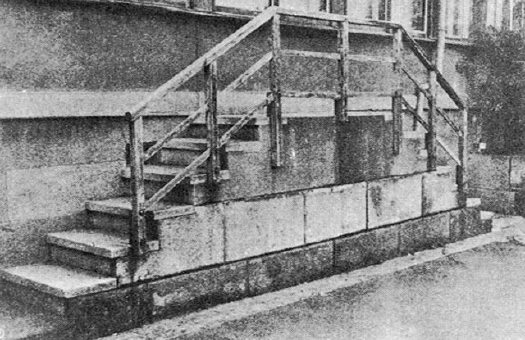

Tomasons [also Thomassons], but really, トマソン, are the inadvertent, useless architectural leftovers, vestiges of a city’s churned and rebuilt history. They were invented/ discovered and documented beginning in the 1980s by the Japanese art/architecture collective Rojo Kansatsu [Roadside Observations] and its co-founder Akasegawa Genpei.

At the time, Japan was in the middle of a crazy, real estate-fueled economic bubble, and the built environment was in constant flux. Akasegawa made Tomasons the humorous, overlooked fodder for a magazine column, the compilation of which became a hit in the 80s.

Now, thanks to Kaya Press, Akasegawa’s Thomasson writings have been published in English. Should be great stuff. [via metafilter]

Previously, 02/08: On Tomason, or the flipside of Dame Architecture

Related: Roadside Observation [neojaponisme.com]

Related from last week: Berthier’s (and Boudvin’s) Door, a fake Tomason in Paris [bldgblog, who else]

The Togs Must Be Crazy

Colorful, cheap African textiles: they’re not just for Yinka Shonibare anymore!

Called Pagne in West Africa and Kanga [also khanga] in Tanzania, 1×1.5m screenprinted cotton wraps are produced all across Africa. There is a tradition to make commemorative kanga for major events, such as the official visit or inauguration of a US president.

Or more typically, the inauguration of a local political leader. Politicians in newly independent nations quickly adapted a traditional practice, and distributed the government-produced fabric for free or at a subsidized cost to their supporters.

As Linda reports in full-color glory on All My Eyes, the Tropen Museum in Amsterdam has a show, “Long Live The President | Portrait Cloths from Africa,” which includes over 100 examples of these textiles. Many come from the extensive private collection of Bernard Collet and can be seen online. The Tropen show runs through August 29th. Obviously, everyone should go.

Even more obviously, though, everyone should be commissioning Pagne and Kanga designers to make commemorative patterns for whatever event or non-event they want to propagandize, too. The mind reels at the awesome possibilities.

African Portrait Cloth [all my eyes]

Long Live The President | Portrait Cloths from Africa [tropenmuseum.nl via all my eyes]

Adire African Textiles [adireafricantextiles.com via a.m.e., like basically everything in this post]

Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant et de l’amateur de photos

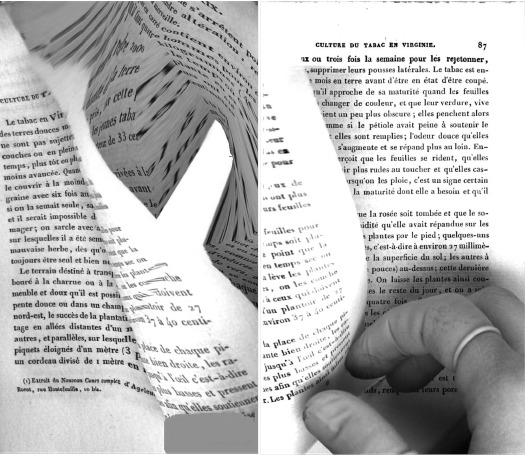

So fantastic. I stumbled across this inadvertent diptych in Google Books, it’s pp. 86-7 of P. Ch. Joubert’s 1844 addition to the Manuels Roret series, Nouveau manuel complet du fabricant et de l’amateur de tabac.

It’s beautiful, somewhere between the process-heavy, content-free abstraction of Walead Beshty and the reverential physical investigations of Abelardo Morell, with a bit of those weird Weegee funhouse mirror photos thrown in for good measure.

And yet they’re also entirely of their own time, place, and making.

A few years ago at John Connelly, my buddies Jonah Freeman and Michael Phelan showed some sweet prints of crumpled aluminum foil shot on a flatbed scanner. [Mitterand+Sanz has images] Which could be a great process here. But I’d really love to figure out how to create negatives from these scans and make up some big, old school silver gelatin prints. [thanks GF-R for the heads up on Morell]

Related from last October: Why is Google giving us the finger? [designobserver.com]

Google Image collection of Google Books Finger [via BoingBoing]

‘Cieli ad alta quota’ by Alighiero e Boetti

Hans Ulrich Obrist, is there anything you haven’t done? In 1993 as part of the Museum In Progress project, Obrist helped the Italian conceptual artist Alighiero e Boetti realize a longtime idea of putting art on airplanes.

In addition to double-page spreads in their in-flight magazine, Austrian Airlines made six seatback tray-sized puzzles available of Boetti’s drawing series, Cieli ad alta quota (High in the Sky).

If any puzzles survived to be collected or traded, they’re not generating the typical online info flotsam. Maybe in this case, it should be jetsam.

Museum in Progress On Board [mip.at]

Everyone’s An Artist

Artist/curator Anton Vidokle reworks an excellent lecture on the problems of curator/artists in the latest issue of e-flux journal

I feel that whereas artists’ engagement with a range of social forms and practices not normally considered part of the vocabulary of art serves to open up the space of art and grant it increased agency, curatorial and institutional attempts to recontextualize their own activities as artistic–or generalize art into a form of cultural production–has the opposite effect: they shrink the space of art and reduce the agency of artists.

Curators claiming the mantle of art for their shows is an issue at least as old as the 1960s, but it has been exacerbated, Anton says, by the demise of the critic’s power. All in all, a sharp read. [via afc]

Related: Gregory Battcock and ‘The Essential Triad’

Pixel Art Minidoc By Simon Cottee

This 11-minute documentary short by Brisbane animator Simon Cottee gives a nice look at contemporary pixel art and its origins.

Unsurprisingly, game developer Jason Rohrer has the most thoughtful perspective on the idealized, ex-post-facto perception of pixels as these perfect, hard-edged squares, which he attributes in part to looking back at old low-res games on new, hi-res monitors.

Cottee et al make the connection between pixels and pointillism, but the focus on animation leaves out the influence both pixel-centric image software, like Photoshop, and pixel-related art shown in galleries. [Juan Cespedes, Cory Arcangel, Sherrie Levine, Joerg Colberg or Thomas Ruff, or even Tauba Auerbach or Gerhard Richter] Still well worth a view.

Slow Cinema vs. Art Cinema

On the occasion of Apichatpong Weerasethakul [1] winning the Palme d’Or, Frieze‘s Dan Fox has a incisive recap of the debate over Slow Cinema that erupted after Nick James’ Sight and Sound recent op-ed calling the genre out as a passive-aggressive dare to the audience to admit they’re bored.

The row among film critics and festivalgoers is as annoyingly insidery and lingo-obsessed as any art world argument. [Fox is careful to give equal time to competing terminologies. One blogger critic, Harry Tuttle, thinks Slow Cinema is pejorative, and proffers Contemporary Contemplative Cinema instead, which seems arbitrary. Might as well call it Minimalist Meditative Movies.]

Fox’s dead-on point is how insulated and blind these two systems of production and distribution–theater/festival/DVD vs gallery/installation/edition–are from each other. And this, despite the remarkable confluence of interests, strategies, and styles among filmmakers and artists on both sides of the divide:

Much as I admire Tuttle’s spirited engagement with his favoured genre of contemporary cinema, nowhere on his timeline of CCC/Slow Cinema is there anything that represents, for instance, the achievements of Structural cinema. This is curious, for if ‘plotlessness’, ‘wordlessness’, ‘slowness’ and ‘alienation’ are what he is trying to chronicle, where are Andy Warhol’s Empire, from 1964, or Michael Snow’s 1967 film Wavelength for example? Nor is there any acknowledgement of how these multiple strands of experimental cinema history have fed into the work of artists today.

Artists such as Tacita Dean, Sharon Lockhart, and Matthew Barney, for example. [On the other side of the fence, I’m not sure why no one seems to have mentioned my own personal favorite Slow Cineman, Gus Van Sant, who emptied Sundance theaters with Gerry and whose lingering, looming Elephant also won at Cannes.]

Barney has broken theatrical and festival ground with his Cremaster Cycle, of course. But I think Frieze, which has commissioned projects from Weerasethakul, has high hopes for him as a candidate for bringing the worlds of these two film traditions together. We’ll see.

Slow, Fast and Inbetween [frieze]

[1] yes, he’s in the art world pronunciation guide.

Slate-Roofed Houses

A couple of months ago, I wondered aloud about the reason Yves Klein schlepped all the way out to the Parisian suburbs to make the leap into the void for his famous photocollage, Leap into the Void.

The site, 3, Rue Gentil Bernard, Fontenay-Aux-Roses, has changed since October 1960, but it houses a church dedicated to Sainte Rita, with whom Klein had a spiritual connection. [A votive offering assemblage Klein made during one of his pilgrimages to St. Rita’s monastery in Italy is in the Hirshhorn’s just-opened retrospective.]

As it turns out, I should’ve just been reading my Art News instead. Kim Levin wrote about Leap Into The Void in the March 2010 issue, and reports that it wasn’t Catholic mysticism, but Klein’s other passion, judo, that drew him to Fontenay-Aux-Roses.

She cites the 2006 obituary for photographer Harry Shunk who, with his assistant Janos Kender, shot Klein as he “climbed to the top of a wall and dived off it a dozen times–onto a pile of mats assembled by the members of his judo school across the road.”

But wait, is it the judo school or the pile of mats that was across the road? After a bit more searching, I found this intro to a 2006 monograph, L’envol d’Yves Klein: L’origine d’une legende, which basically puts Fontenay at the center of Klein’s story. [It might help that it was written by a couple of Fontenaysiens, Terhi Génévrier-Tausti and Pierre Descargues.] Anyway, Klein was raised there, and his friend had the Olympic Judo Club there. So yeah.

The best part of Levin’s story, though, comes from Michelle White, who curated “Leaps into the Void: Documents of Nouveau Réalist Performance,” at the Menil:

after she discovered an odd object in the Menil archives: a piece of slate. It wasn’t art–just a piece of slate “collected” by Dominique de Menil in 1981 from the mansard roof that Klein presumably leaped from.

The Matteses would be so proud.

White’s show includes other photos from the Leap, including this spectacular action detail, which are in the Menil’s holdings:

Looks like someone’s gotta book a trip to Houston.

Yves Klein’s Leap Year [artnews via @johnperrault, yes, he’s on twitter now]

Leaps into the Void: Documents of Nouveau Realist Performance, through August, 8, 2010 [menil.org]

National Houses, Inc.

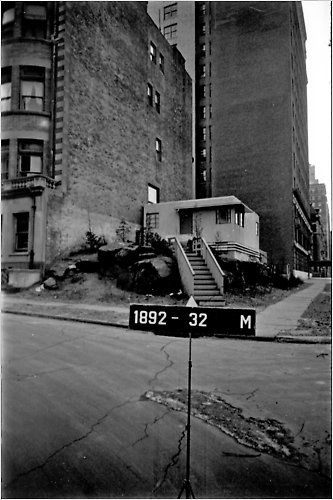

So weird/awesome. A steel panel, prefab, moderne house designed by William Van Alen, and built on top of a craggy boulder at 107th & Riverside, in 1937, seven years after completing his somewhat higher profile project in Midtown, the Chrysler Building?

Christopher Gray has the story–and finds this picture in the Municipal Archives–in

NYT’s Streetscapes column.

According to “A Home in Cellophane,” a chirpy 1935 Time story about prefabs [found via the Van Alen Institute], Van Alen was actually a director of National Houses, Inc., just one of several prefab startups that were going to pull America’s housing market out of the Depression.

The focus of Time’s article was actually another venture, American Houses, Inc., who unveiled architect Robert McLaughlin’s modular, modernist “machine in which to live,” the Motohome, at Grand Central Palace, the same place where Albert Frey & Lawrence Kocher’s Aluminaire House had debuted in 1931. [Aluminaire was extensively re/dis/covered here on greg.org in August 2009. Here’s a contemporary photo by curator Erik Neil of the house, which is currently on the Islip campus of the NY Institute of Technology.]

Aluminaire was a hastily constructed one-off; the Motohome was a product. It went on “sale,” tied with a red bow, and wrapped in cellophane [like the future!] at Wanamaker’s department store on April 1. [The half of Wanamaker’s that didn’t burn to the ground now houses the Astor Place KMart.] There must be some publicity shots or newsreels of this somewhere.

As our country is not dotted with tens of thousands of early International Style or Moderne steel- or asbestos cement-paneled cottages being tended and detoxified by new generations of design-loving caretaker owners, these products failed.

American Houses scrambled to traditionalize its design and materials, and apparently sold around 150 peaked-roof, woodframe Motohomes by 1938. But as of 1991, it sounds like only two of McLaughlin’s original modernist Motohouses were still standing; that was when one was discovered in New London, CT, and preservationists persuaded its owner, Connecticut College [image via] to restore, not demolish it. Now the College is working to restore the other modernist prefab next door, dubbed The House of Steel. [Both were bought and used as rental properties by an adventurous museum director named Winslow Ames, who wanted to test the 1930s media’s prefab hype.]

Van Alen’s National Houses designs did not fare so well. In 1936, his 2-story steel prefab design, called “The House of the Modern Age,” was erected for three months on a vacant lot at 39th & Park. It’s the little white box in Berenice Abbott’s photograph:

The house at 107th & Riverside was an exhibition house, too. And it was obviously torn down, because if it still existed, I’d be living in it. I can’t find any other mentions of Van Alen’s prefab structures being built, much less surviving.

[2022 UPDATE] Did I hallucinate or didn’t at least one of Van Alen’s houses get transported to Westchester somewhere, and I saw it for sale a couple of years ago buried under an epic amount of upscale renovations?

What I do know is that Dan Nichols emailed to say he came across a Van Alen house in Miami. Apparently in 1936, Clarence Beecher, the Florida rep for National Houses, Inc., built himself a company house in Shorecrest, off Biscayne Blvd. It has been subsumed by the local vernacular: stucco and tile roof, but in its heart beats the metal paneled prefab House of The Future.

Oh My Heck, Spiral Jetty India Pale Ale

That is so Epic.

From Epic Brewing Company, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Spiral Jetty IPA | Epic Brewing Company [epicbrewing.com via the freshly relocated tyler green]

Related? The Shoppes at Rozel Point, from Visiting Artist (sic), a lecture involving Smithson which I gave at the University of Utah: