The New Yorker obsoleted my old New Yorker Magazine Database by finally letting Google index their website and adding a search function, and making their archive available online, and that’s as it should be.

But whenever I browse the DVD facsimile of the magazine’s archive, I am reminded of how much content remains unindexed and invisible. So maybe it’s time to liberate the vintage ads of the world from their back issue prisons. Because if I can find ads this awesome completely at random, don’t you wonder what else is out there?

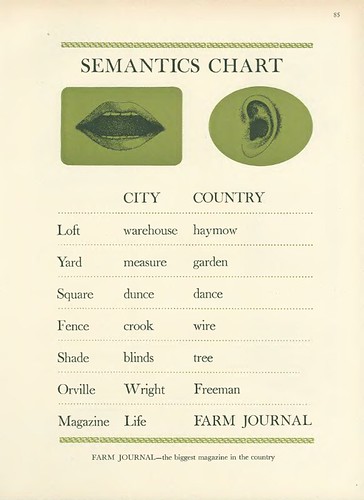

Haymow!

Author: greg

Van Gogh, Haring, Razzle Dazzle: Car Camo Wraps

I love it when a tossed-off plan comes together. In this case, it’s the idea of artist-designed vinyl car wraps. And camo.

The Times had a great story about auto spyshots, and the increasing use of camouflage vinyl wraps on test cars. Some of the wraps seem designed to thwart a spy photographer’s focus, or at least to obscure the contours and details of the car.

The different patterns are discussed as resembling “a Keith Haring painting,” and “World War I ‘dazzle ships,'” or as sporting the swirly, painterly “Van Gogh Look.”

It should only be a matter of time before a collection of contemporary artist vinyl wraps hits the streets. Right?

Secret Cars Kept Under Wraps, in Public [nyt via slow and steady wins the race]

Previously:

The Jeff Koons wrapped BMW

Vinyl wrapped art car: Hirst]

First or worst? Peter Max decal car c. 1968

Razzle Dazzle and Dutch Google Maps camo

OG WWI dazzle design and the Koons revival

Short Circuit Flag: Finch Is Off The Hook

There’s some interesting background info as well, but the big news [sic] today in piecing together the history of Rauschenberg’s Short Circuit is that Finch College is off the hook–and Holland Cotter is right after all.

Continue reading “Short Circuit Flag: Finch Is Off The Hook”

James Turrell At Kijkduin

Does an Anglo calling The Hague “Den Haag” sound as obnoxious as one calling Florence “Firenze” or Milan “Milano”? This is not a rhetorical question. I really need to know.

Celestial Vault in 1996, James Turrell, image via: stroom.nl

In 1996, Stroom, the contemporary arts center in Den Haag [!] commissioned a permanent public sculpture from James Turrell. And while Stroom has certainly achieved much since then, it still seems like the most prominent/significant thing they’ve ever done.

Celestial Vault was built in Kijkduin, a duney seaside suburb about a 20-min. bus ride from the center of town. It consists of two parts: a contoured, elliptical, crater-shaped earthwork with an inclined viewing platform at the center, and an another platform installed on a higher, adjacent hilltop.

The weather and use had taken a toll, and so in 2008, a significant effort to restore Celestial Vault was undertaken. Stroom’s website says the work is open to visit, so I did, only to find warning tape placed across the tunnel entrance to the crater. Obviously, I went in anyway. [On Google Maps, the dune crater looks to be hard up against a restaurant and a baseball diamond, of all things. When you visit it, the topography is such that these both fall completely away.]

It seems so online, and it was really apparent in person, that Celestial Vault functions as a kind of experiment or test run for Turrell’s project to reshape Roden Crater. For that reason alone, it seems like it should get more attention than it does. [Is it just me? I follow Turrell’s work, and his 1993 retrospective at ICA Philadelphia is a longtime favorite, but it seems the Roden Crater hype overshadows everything else. I’d never heard of Kijkduin, and frankly stumbled on it by accident on my morning visit to Den Haag.]

Also, it’s actually built. And you can see it without being on a 10,000-year waitlist or whatever Roden Crater’s gonna have.

All that said, I confess I couldn’t get Turrell’s vaunted vaulting effect to work. Maybe I didn’t stay still long enough of free my mind or unfocus my eyes or whatever long enough. Maybe I was focusing too much on the rain that was falling on me the entire day. But Turrell [and the Dutch, for that matter] are rather specific about the material qualities of Kijkduin light, and the overcast, rainy lightbox effect IS pretty standard there on the North Sea.

So maybe it was me, and I was wrong to expect something less subtle, a more special-effectsy, fish-eye lens distortion.

Because what you end up with–or what I ended up with, anyway–was a view of the sky where the [shaped] horizon line hovers just barely on the edge of your peripheral vision. The fact that the vaulting worked almost the same way with the actual horizon line, which Turrell used on the hilltop platform, kind of makes you wonder if the whole earthworking effort isn’t more for its own sculptural properties than for facilitating any actual retinal impact.

It’s a question Turrell seems to have been asking himself, by placing these two identical viewing platforms side by side, but in opposite geographic situations. I guess since work really picked up at Roden Crater since Kijkduin was built, Turrell got the answer he was looking for.

Stroom page with info and tons of photos: James Turrell – Celestial Vault, Kijkduin, Den Haag [stroom.nl]

Celestial Vault on Google Maps [google]

My Turrell @ Kijkduin photoset on flickr [flickr]

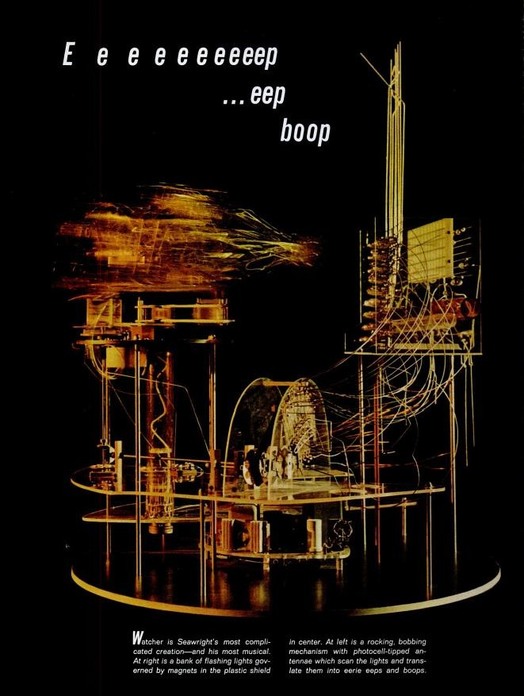

Whoa, James Seawright

It’s crazy sometimes how long it takes to see what’s right in front of your face. I’ve been thisclose to artist James Seawright’s kinetic and electronic sculptures over the last couple of years, and yet I only really discovered them yesterday.

Seawright, who was for a long time the head of visual arts at Princeton, began making Bauhaus-inspired light and sound performance works with his dancer wife in the early 1960s. Bauhaus in this case meant Laszlo Moholy-Nagy, whose Light Space Modulator has been much discussed around here.

Trained as an engineer, Seawright began taking sculpture classes at the Art Students League in New York, and scored a solo show at Stable Gallery in 1966. Among his awesome work in that show: Watcher (1965) [above, from a 1967 LIFE Magazine spread.]

Like much of Seawright’s work, Watcher is designed to activate and react to the presence of the viewer–or to itself–via photovoltaic sensors. It looks remarkably similar, both formally and functionally, to the Eames Solar Do-Nothing Machine (1958).

After his Stable Gallery show, Seawright was involved in shows at Howard Wise, and was one of a handful of artists–along with Allan Kaprow, Otto Piene and Heinz Mack–to participate in The Medium is The Medium, an early experiment in video art/”tele-Happenings” produced by WGBH in 1969. Which I now must watch again, for the Seawright part.

James Seawright [wikipedia]

seawright.net [the artist’s portfolio site]

Gala As Art Talk: The Making Of

I was nervous, I admit, but I really had a blast last week giving my Gala As Art presentation last week at #rank. The crowd was great; the other #rank folks I met were nice, with interesting projects and conversations; SEVEN looked fantastic, a really smart, low-key way to show a fair’s worth of work [I hope all the participating galleries made a bundle of money.]

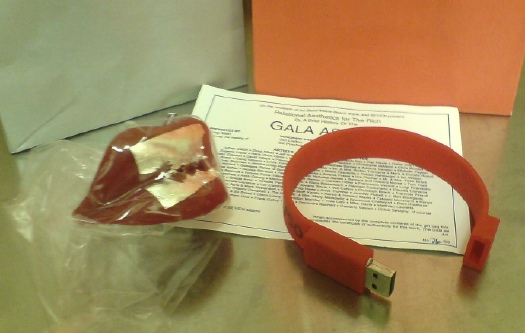

It seemed obvious that the talk required gift bags, so I decided to do them as an edition. The artist-licensed perfume I hoped to include didn’t pan out, though. I’d toyed with the idea, no pun intended, of making a version of Marina Abramovic’s party favor/dessert for the The Artist is Present gala, where the dessert art foundry Kreemart cast her lips in Belgian chocolate covered with gold leaf.

Then I priced edible gold leaf, and opted for silver leaf on edible wax lips, which really set the gift bag’s entire color scheme. [Actually, Diet Coke probably set the color scheme without me being aware of it.] Applying silver leaf was a pain in the butt, but there were only a couple of rejects. They traveled amazingly well, thanks to Jean’s careful wrapping. The certificate is designed like an invite, with a bajillion artists and collectors and curators on the committee, everyone I mentioned [or planned to, anyway.]

And at the last minute, I decided that burning and printing 50 DVDs full of the gala-related video and pdf files I’d assembled would be not so interesting. [A friend pointed out that no one ever opens the jewelcases in their gift bags, and I realized, in 20 years, I never had either.]

So I hustled to find a cool USB drive I could load. Maybe get my logo or url on it. Or maybe find anything at all in stock. Finally, I found exactly what I was looking for, and I ended up loading, signing and numbering the silicone bracelet flash drives the morning I left.

I’m discussing them at length here because they’re apparently so stealth, several people didn’t realize they were anything more than a wristband. So now you know. I saved a couple for the archive. And because I didn’t want to leave the lips melting in the trunk, I ended up not going to Art Basel at all. Crazy.

Meanwhile, I’m trying to find the best/easiest way to release the slideshow and audio together, either as a screencast or a podcast or something. Watch this space.

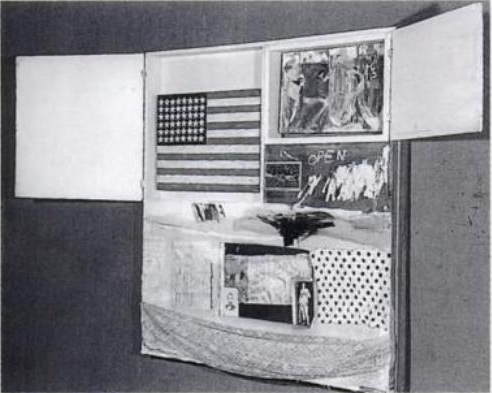

Jasper Johns’ ‘Short Circuit’ Flag: One Place It Isn’t

After a brief break, during which I briefly pwned Miami Art Basel, the search for the Jasper Johns flag painting which was included in Robert Rauschenberg’s 1955 combine-painting Short Circuit [above], continues.

Actually, because I had to carry on the oddball contents of the gift bags I did for my #rank presentation, I went to the airport freakishly early and ended up with extra lounge time, which let me read through all the details and footnotes in my pristine, OG copy [apparently from the library of Artforum!] of Dr. Roberta Bernstein’s definitive 1985 dissertation-cum-catalogue raisonné, Jasper Johns’ Paintings and Sculptures 1954-1974, “The Changing Focus of the Eye.”

Only guess what, it wasn’t there. Not a mention, not a photo, not a footnote, not a trace.

[UPDATE: Since posting this in December, I have communicated with Dr. Bernstein about the Short Circuit flag and its absence from her thesis, as well as its status in her forthcoming Johns catalogue raisonne. Scroll down for her gracious and informative reply.]

Continue reading “Jasper Johns’ ‘Short Circuit’ Flag: One Place It Isn’t”

Dance + The Whole World = The Whole World

Via Ubu comes a provocative essay, “Constructed Anarchy,” from the poet and John Cage critic Marjorie Perloff. She takes the death of Merce Cunningham and the company’s plans to dissolve after a worldwide farewell tour as an opportunity to ask a tough question of Cunningham’s and Cage’s philosophy: basically, if art is life, what happens to it after you’re dead?

When in June 2010 I had the chance to see Roaratorio performed at the Disney Concert Hall–a beautiful Roaratorio but no longer graced by the presence on stage of Merce or by the actual speaking voice of John Cage–what seemed especially remarkable was the tight formal structure of a composition once billed (both in its radio and dance incarnations) as an anarchic Irish Circus, bursting with random sounds and unforeseen events. For, however differential the leg, arm, and torso movements of the individual dancers (sometimes in pairs or threes, sometimes alone), all are metonymically related in a network of family resemblances, and all are, as the charts show, mathematically organized. Yet wasn’t it Cage who defined his music as “purposeless play”–“not an attempt to bring order out of chaos . . . but simply a way of waking up to the very life we’re living, which is so excellent once one gets one’s mind and one’s desires out of its way and lets it act of its own accord”? And wasn’t it Cunningham who insisted that dance “is not meant to represent something else, whether psychological, literary, or aesthetic. It relates much more to everyday experience, daily life, watching people as they move in the streets”?

The very life we’re living: the Gelassenheit so seemingly central to Cage-Cunningham was hardly anarchic, much less unpredictable. But their own statements, and hence the critical writings about their work, have regularly insisted on what Joan Retallack, in her seminal series of conversations with Cage, calls “an aesthetic pragmatics of everyday life.” “[Cage] told me,” she recalls in her Introduction, that “the art that he valued was not separated from the rest of life. . . . The so-called gap between art and life didn’t have to exist” (Musicage xix-xx). And Cunningham repeatedly made the same point, using traditional ballet as contrast.

Or that’s how it used to be.

It sounds convincing: to see RainForest or Roadrunners, Channels/ Inserts or Beach Birds, is to perceive that there is no central focus or storyline, no prima ballerina flanked by a corps de ballet, no symmetry or detectable unifying principle. But if the dancers are free to introduce their own variations and tempo, if the piece is as non-hierarchical and collaborative as Merce suggests, why has each work (dance and music) been plotted out geometrically and arithmetically? Why have the dancers received so much less acclaim than Cunningham himself, in his role as director /producer /choreographer? And why has the decision been made that the ensemble will not be able to function without him? Similar questions can be put about Cage’s work: is his recorded voice reading Roaratorio essential to the work? Can a “decentered” Cage Musicircus perform without Cage?

The more we probe such Cunningham-Cage concepts as “free form” or “anarchy,” the more apparent it becomes that theirs is an anarchy that is carefully simulated. Their works are by no means “happenings,” in Allan Kaprow’s sense of the word, nor is Cunningham producing performance art.

As in Duchamp’s case, no “accident” is really accidental, and discipline is central. [emphasis added because, yow, kinda harsh]

Perloff’s argument is definitely worth a read, and she had a front row seat–and she quotes longtime Merce collaborator Carolyn Brown and others–on Merce and Cage’s egos and steely artistic wills, which seem to undermine a carefully cultivated [or at least prevailing] laissez-faire, see-what-happens image.

But I’m just half-informed enough to take issue with Perloff’s takedown. She sets up seeming contradictions between professions of randomness and artistic control, but I think that’s false and unfair. Cage wasn’t an evangelist for randomness, nor for anarchy, but for chance and chance operations. And there’s a meaningful difference that I suspect Perloff knows well.

Randomness is whatever happens, but chance operations is a tool for determining what happens. Perhaps Cage and Cunningham’s meant their obliteration of the distinction between art and life, between music and sound, between dance and movement, to be a production strategy for the artist, not a life strategy the audience.

Constructed Anarchy [lanaturnerjournal.com via ubu]

Interesting/related, and the 2nd time in 2 days to see Cage compared to Warhol: Ubu founder Kenneth Goldsmith’s 1992 review of Perloff’s first posthumous Cage essay. [electronic poetry center]

Bruce Weber’s Next Book Will Be Titled, Let Me Help You Out Of Those Wet Things

In my talk at #rank in Miami Friday, I called for more scholarship on the growing genre of yacht art. Which, via this NY Times Style section slideshow caption, now includes at least one work of hybridized performance/institutional book party critique by the artist Al Czervik:

During a high school band performance at the Bruce Weber and Andre Balazs party at the Standard Hotel, a massive yacht passed the dock, sending three enormous waves crashing up through the dock, drenching the guests.

Until Taiwanese animated news comes up with something, this youtube video will have to do.

Johns, Merce, Duchamp: Walkaround Time

image: walkerart.org

Welcome to one of the oldest tabs in my browser: the inflatable balloon set for Merce Cunningham’s 1968 piece, Walkaround Time, which is based on Marcel Duchamp’s Large Glass, which was made by the company’s artistic director at the time, Jasper Johns.

I’d backed into the pieces–seven cubes of silkscreen-and-paint on clear vinyl, reinforced with aluminum frames–a few months ago, and realized I’d seen them–and not thought much about them–at the opening of the newly expanded Walker Art Center in 2005.

Which I now regret, but which makes Merce’s title resonate a little more. Cunningham dancer and longtime collaborator Carolyn Brown explains that Walkaround Time was a reference to a particular kind of purposeless movement taken from ancient computer history, when “programmers walked about while waiting for their giant room-sized computers to complete their work.” It’s just taken me this long to appreciate–or even to see–the work. And for some great additional links to appear.

I can already tell this is going to go long.

03/2012 UPDATE: Unfortunately, none other than former MCDC stage manager Lew Lloyd informs me that the term “balloon” is not really accurate; they were transparent vinyl boxes fit onto armatures, which could be broken down for travel. Given my noted satelloon bias, I will still think of them as balloons in my heart. For the rest of you, though, remember: not balloons. [end update]

‘It Gets Better’ Doesn’t Mean The Bullying Stops

I recently went with my daughters to see “Hide/Seek” at The National Portrait Gallery. They’re 2 and 6, so most of the content of the show is way over their heads. [Much of the work, like the vintage photographs, was literally over their heads.]

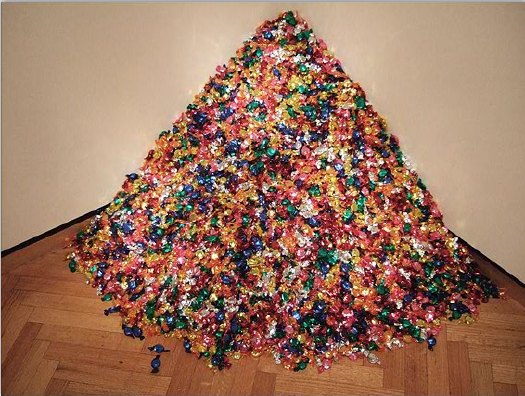

Felix Gonzalez-Torres’ shiny, multi-colored candy pour, Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA) was an immediate and repeated hit. As my kids were going back for “just one more piece,” I laughed with other visitors at the sign the museum had posted next to it, warning that these small candies might pose a choke hazard.

At first I was going to write that we mostly stuck to the bright, colorful works, but that’s not correct. While a giant camo Warhol was front and center, and the kids both recognized it immediately, I didn’t think either one would be ready for the most colorful work in the show, A.A. Bronson’s massive, epic portrait of his AIDS-ravaged partner Felix’s body. Fortunately, the curators had placed it in its own semi-enclosed niche, to the side. It was a careful presentation of a devastating and important work, thoughtfully non-confrontational without seeming sequestered or hidden.

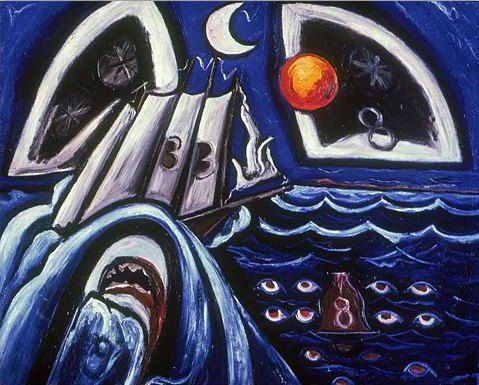

We saw Jasper Johns’ face on a plate. Larry Rivers’ giant nude portrait of Frank O’Hara, which was hard to miss, of course. We played I Spy with some of Marsden Hartley’s elements–the ship, the waves, the bells, the sun &moon, the shark–in his Memorial for Hart Crane. The older kid read the title, so we talked about the painting for his friend who drowned. I couldn’t not tell her that Crane had jumped from the ship, not fallen. No, I didn’t know why, except that he must have been very, very sad and thought that his life was so bad, it’d be better to be dead. Which we decided did not make sense and was not true.

We saw the lady in the tuxedo and laughed at the very idea that long ago, some people thought only men could do things like work, or vote, or paint. And that there were things people thought only women do that men shouldn’t–like pose nude for a painting [gesture to giant, nude Frank O’Hara].

We talked about David Wojnarowicz’s self-portrait, above. And that when he knew he was dying, he made a picture that looked like he was buried. Or maybe it looked like he was coming out of the ground.

There were two small video monitors and a touchscreen, which attracted the 2yo like a giant iPad, but we didn’t come to a museum to watch TV [this time.] One turns out to have been an excerpt from the David Wojnarowicz film, A Fire In My Belly, which the NPG just censored on the demand of William Donohue of the Catholic League, the self-appointed arbiter of offenses to Christian sensibilities. Republican leaders in the House of Representatives seized on the work and the show and demanded the Smithsonian cancel it immediately.

Pulling Wojnarowicz’s work in the face of such bullying is a breathtakingly cowardly betrayal by the museum, one which either ignores or mocks the artist’s own work and history. That it’s happening on World AIDS Day, that Wojnarowicz’ work is singled out for silencing on what used to be called A Day Without Art, is deeply offensive and damaging to the artist, the show, the curators, the museum, and to the principles of our country.

From Michael Kimmelman’s obituary for Wojnarowicz in 1992:

Like the artist himself, his art never pulled punches. Mr. Wojnarowicz gained the national spotlight in 1989, when the National Endowment for the Arts decided to rescind money for a catalogue to an exhibition about AIDS because of an essay in which he attacked various public figures. The endowment reversed itself. It also supported a 10-year retrospective of his work that was organized at the University Galleries of Illinois State University in Normal, Ill., which included a catalogue that reproduced the essay.

Mr. Wojnarowicz was in the news again after the American Family Association of Tupelo, Miss., an antipornography lobbying group, and its leader, the Rev. Donald E. Wildmon, issued a pamphlet criticizing the endowment. The pamphlet included photographs cropped from works by Mr. Wojnarowicz that included sexual images. The artist sued the organization for misrepresenting him and damaging his reputation. In 1990, a Federal District Court judge in New York ruled in his favor and ordered that the organization publish and distribute a correction. Mr. Wojnarowicz was the only artist to challenge Mr. Wildmon in court.

If the exact same people and groups attack the exact same artists and institutions and outcome is actually more punitive–remember, the NEA reversed itself and Wojnarowicz stood up to his critics and won–how can we call it progress? It doesn’t get better by itself.

update: Incredible. Tyler’s confirmed [2024: link updated] that it was Smithsonian Secretary Wayne Clough who ordered the Wojnarowicz video pulled. From the way it went down, it sounds like he censored the video over the objections of the NPG staff–and without even watching it himself. Not that the content is at all obscene or even offensive. To anyone whose job isn’t professional offensetaker, that is.

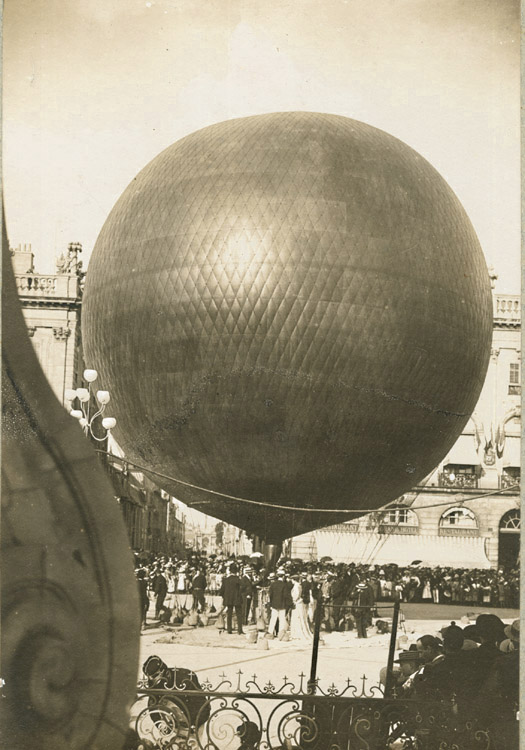

Henri LaChambre And His Nancy Balloon

Rather than post this beautifully composed 1895 photo of Henri LaChambre’s rather awesome gas balloon inflated at Nancy, I should’ve freakin’ bought it by now.

Of course, my problem is that, now that I’ve seen it, I’ve filed it away for future flea market reference, where I’m sure I’ll just stumble upon a photomural-sized print of it for a euro.

Anonymous – Henri Lachambre and His Balloon at Nancy, France, $450 [vintageworks.net, thanks to whoever sent this to me, I forget, sorry]

Previously: Les Ballons du Grand Palais

Drawing About Architecture About Music

I’ve got a lot of browser tabs to clear before I head to Miami.

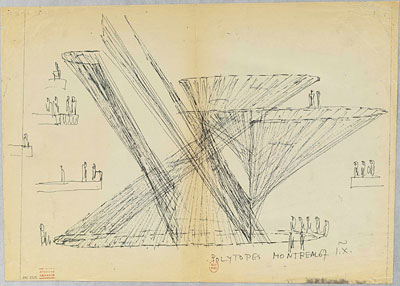

Am I not listening or looking in the right place, or is there really not enough discussion about MoCA’s exhibition of drawings by the composer/architect/polymath Iannis Xenakis?

Xenakis was a longtime collaborator with Le Corbusier. Philipp Oswalt credits him with the introduction of light and projection as tools and “subject[s] of architecture” in the dramatic chapel of the convent at La Tourette.

Tools which would come in handy in the multimedia Poeme Electronique, whose film projection cones and soundscapes drove the form of the 1958 Philips Pavilion [top].

Anyway, the drawings include musical scores, which sometimes appear interchangeable with Xenakis’ schematics and sketches for his later independent installations, including the Polytope for Montreal, above, an abstract light and sound environment, which he created around the time of Expo 67. The Xenakis archive is at the National Library in France. Not sure how accessible it is, but LA might be the best/easiest shot.

Related: Philips Pavilion models spotted in Amsterdam

‘Relational Aesthetics For The Rich’ – Friday 12/3, 1PM In Miami

It’s less than a week away, and I can’t believe I haven’t hyped it yet:

I’m giving a presentation this Friday in Miami during Art Basel Miami Beach titled, “Relational Aesthetics For The Rich, Or A Brief History Of The Gala As Art.”

It’s based on this similarly titled blog post, which pulls together a lot of things I’ve been fascinated by over the years, but which was inspired by MoCA’s Annual Gala, which the museum relabeled “a Happening,” and which they turned over to Doug Aitken to design as an artwork.

At least that was Jeffrey Deitch’s original pitch; the results–and the history and context of museum gala art–turn out to be a little more complex.

Anyway, the talk is part of #rank, a program put together by Bill Powhida and Jen Dalton, which will be held at SEVEN, the shared exhibition and program space in Wynwood organized by a group of awesome New York dealers.

There are so many people to thank, starting with Magda Sawon from Postmasters and artist Michelle Vaughan, who are the honorary co-chairs of the presentation. And there are the gift bag sponsors, of course, who will be announced soon. I hope.

The gig goes down at 1pm, and it should be available for live streaming online, in case you are too busy making acquisitions at ABMB or something. But then you won’t get a gift bag…

Jean Nouvel Should Build A Better Bedouin Tent

At least now we know what NY Times museum building critic Nicolai Ourossoff has been up to lately.

Just as I am thinking I need to add Saadiyat Island and the names of the grand new patrons of the arts from Qatar and Abu Dhabi to the greg.org art world pronunciation guide, I find a few things blocking my view of Our Glorious Cosmopolitan Future.

Since at least as far back as Rem Koolhaas bold, neo-Nixonian embrace of CCTV, a policy of architectural engagement has liberated our Western starchitects from the tyranny of conscience, of having to think or worry about the political or ethical unpleasantness of their state clients. I guess that exemption extends to our Western, liberal institutions, too–our Louvres, our Guggenheims, our NYUs, our Georgetowns.

But seeing as how I am not in one of these cultural oases and thus am not at risk of getting fired, deported, or arrested, I’ll just put some of the problematic parts in bold:

The consultant who works in fear of losing his/her job:

“There are religious extremists everywhere in the Middle East — even here,” said an Arab consultant who has worked on several developments and spoke on the condition of anonymity for fear of being fired. The sheik, this person said, believes the cosmopolitan influences of the projects may help “open up the minds of these younger Emiratis before they go down that road.”

The international museum franchises walled off in hermetic playgrounds for the ruling class:

The new museums will be embedded in a kind of suburban opulence that can be found all over the Middle East, but rarely in such isolation and on such an expansive scale as in Abu Dhabi. The concrete frames of a new St. Regis hotel and resort and a Park Hyatt are rising just down the coast from the museum district, along Saadiyat Beach. Nearby, a 2,000-home walled community is going up along an 18-hole golf course designed by Gary Player, to be joined eventually by several more luxury residential developments and two marinas for hundreds of yachts. A tram will loop around Saadiyat, connecting these developments to the museums.

But wait, didn’t Jean Nouvel just say he’d “always wanted” to “make the museum part of the city, not just a building?”

The temporary workers’ paradise that doesn’t actually exist yet, except as a tourist stop for foreign reporters:

In some sense this village embodies a version of the cosmopolitanism Abu Dhabi says it is trying to create. But even if it is completed as planned, it will house only a small fraction of the city’s hundreds of thousands of migrant laborers; the rest will presumably live in cramped quarters in the city’s industrial sector or in faraway desert encampments. And once the museums are completed, a spokesman for the government development agency told me, it will be bulldozed to make room for more hotels and luxury housing.

And the kicker:

Even many educated Arabs in and outside Qatar — among the museums’ target audience — see a disturbing inconsistency in these grand plans.

“Some have lived here 50 years,” said Fares Braizat, a Jordanian professor at Qatar University who has been working on a census of foreign nationals. “They speak Arabic with a Qatari dialect, but they are still not allowed Qatari citizenship” or any of the enviable perks that go with it: free education and health care, interest-free government loans, preference in hiring, a sense of equality.

Here I would have to take issue with Mr. Ouroussoff’s characterization. Whatever feeling a Qatari citizen derives from his large, exclusive bundle of “enviable perks,” a “sense of equality” is clearly not among them.

But it’s not all bad. There’s something about Qatar’s National Museum that gives me hope:

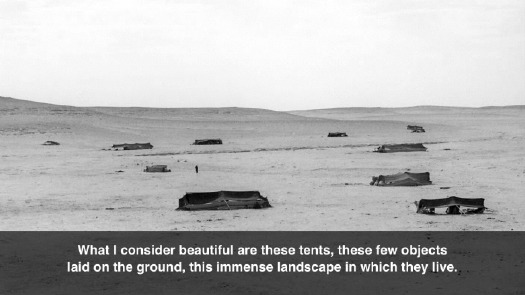

Inside, displays of tents, fabrics, saddles and other objects, as well as enormous video screens that will immerse the visitor in the experience of the desert, are meant to convey both the humble origins of Qatar’s royal family and the nobility of Bedouin life.

If we can get work through our tribalistic present, beyond both Qatar’s exploitative foreign worker practices and American jingoist sneers at the mere mention of Al Jazeera, maybe there will be a shared, globalized, nomadic future where the humble nobility of Bedouin life is celebrated as an aspirational ideal, not just an exotic throwback. Maybe a culture rooted in hospitality and mutual responsibility that subsumes, or at least reconciles the twin forces of rootless disconnection and nationalism which shape each individual’s worldview.

I’m not sure where billion-dollar museums shaped like falconry hoods or hyper-magnified sand crystals will fit in such a culture, but maybe that’s the point.

Building Museums, and a Fresh Arab Identity [nyt]