I’m done waiting. This Europera 1 & 2 post is apparently not going to write itself.

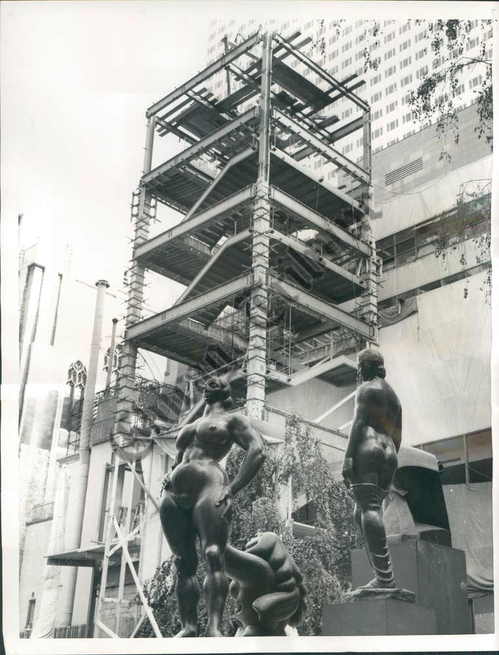

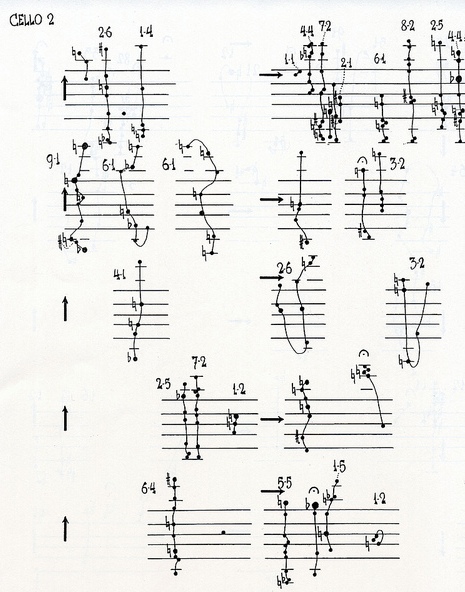

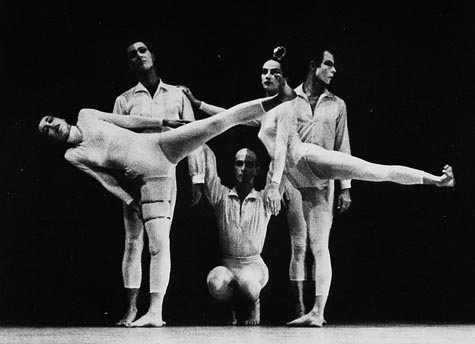

The Ruhr Triennial opened last weekend with what is only the third [production and fourth -ed.] staging of John Cage’s grandest* composition, the 1987 Europeras 1 & 2. It’s basically a chance operations tour de force that runs the entirety of the European opera canon–arias, stories, costumes, props, sets, lighting, libretti, staging, orchestra–through the I Ching wringer, which performance is conducted, so to speak, by the cues of a 2.75-hour clock. As Cage put it, “For 200 years the Europeans have sent us their operas. Now I’m returning all of them.”

All six performances in the Triennial’s home venue, the vast, repurposed industrial Centennial Hall Bochum sold out immediately. So far three have happened, directed by the director of the entire Triennial, avant-garde composer Heiner Goebbels.

So I’ve been monitoring the reviews jealously, and with some indignation. The scale and ambition and significance of the work is being respected—the work has only ever been performed in Germany [update below: not true]—but it seems that both critics and directors alike still struggle with the vocabulary and the very concept of Cage’s chance-driven work.

In the only English-language review I’ve found so far, The Financial Times’ Shirley Apthorp describes Europeras’ “extravagant evening of associative nonsense” as both “chaos” and “minutely choreographed absurdity.” Writing for FAZ Eleonore Buening criticized Goebbels for putting the “chaos Cage conceived a quarter century ago back in a Museumsvitrine.” If I read my German correctly, “The director placed too little confidence,” Buening writes, “in the expiration of the clock, the will of the participants, or even Comrade Chance.” And did Cage ever have a better comrade?

I have never seen Europera 1 & 2, but I’ve been studying up on them for the last year or so. The original staging, commissioned in 1985 by the Frankfurt Opera, was the dissertation subject of Laura Kuhn, who was involved in the production, and who has since become the director of the John Cage Trust.

Europera 1 & 2 strikes me as a simultaneous negation and celebration of opera as an art/theatrical form, but also as a cultural and historical institution. His chance-based composition removes narrative, character arcs, literary and stage conventions, and authorial intentions from the experience of a performance. Chance is not chaos or absurdity; it’s a different syntax. How does any opera performance seem if you don’t know the story or speak the language? Would you ever call it chaos or nonsense?

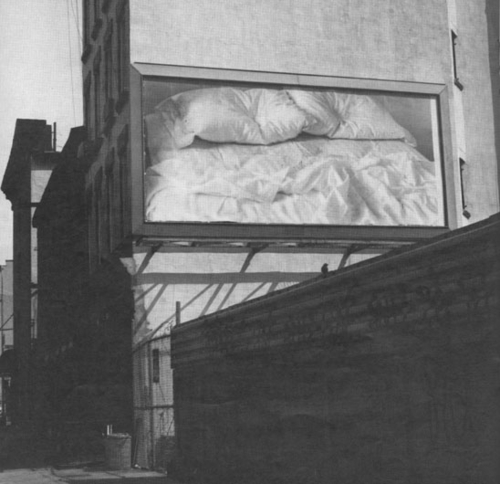

An opera diehard may want to identify the source of every passing prop, aria, or orchestral passage in Europera—did the Stump The Operahead trivia quiz during the intermission of the Met’s weekly radio broadcast ever tackle Cage? Just like a moviehound might try to flag the source of every clip in Christian Marclay’s The Clock. But that risks missing Cage’s point [which is not Marclay’s]: that the experience of the montage has quality and meaning and value in itself, apart from the original content and its juxtapositions, not because of them.

And maybe critics actually are better attuned to this now, and the problem [sic] is just/still the directors. In FAZ, discussing the “Children’s Jury” who Goebbels convened to award unconventional prizes during the Triennial, Buening found a new twist on the classic MTV Crisis when she worried that the media-saturated, “Multi-tasken” Kids These Days might be bored by Cage’s 1980s jump cut revolution. After watching a rehearsal of Europera Ruhr Nachtrichten writer Julia Gass said Cage foreshadowed the “TV Zapp Era”; actually, he was soaking in it. Cage’s vision of the future was surfing the 400 operatic channels of the past.

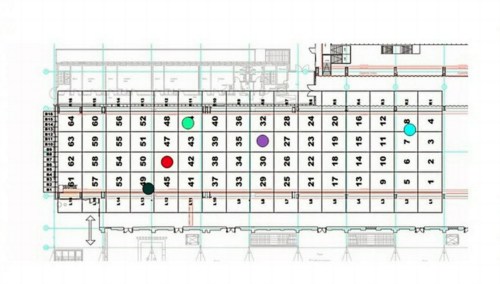

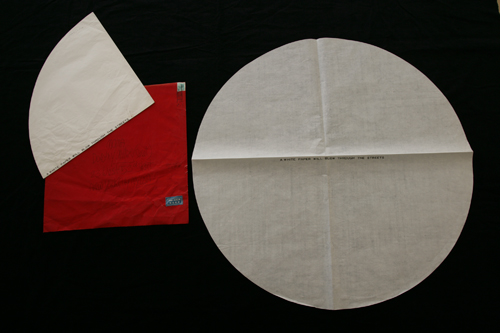

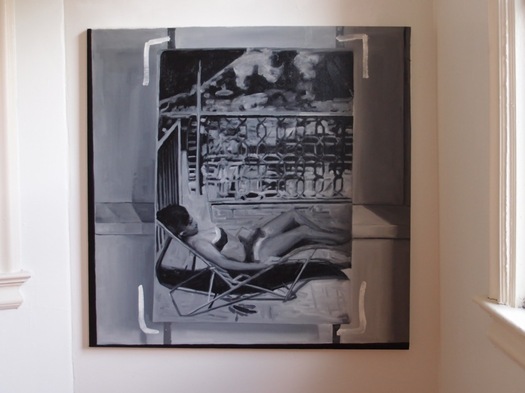

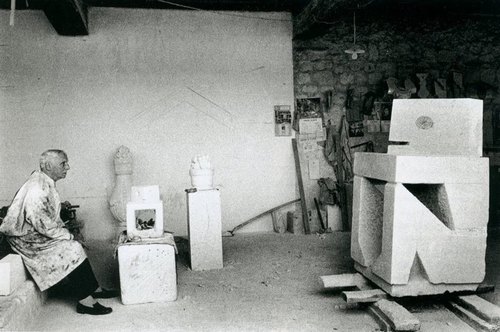

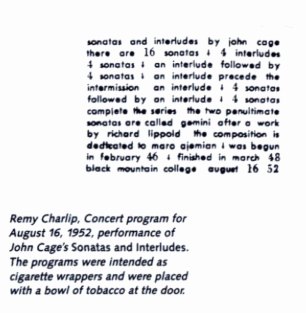

Europera may be Cage’s most ambitious and explicit appropriationist work. According to Kuhn’s firsthand account of the making of, Cage, relying on the collection of Lincoln Center’s library, determined to include only operas that were in the public domain. For the flats and sets, he had researchers in Germany compile engravings and illustrations of composers, architecture, and animals from pre-20th century books. With these copyright-free source sets established, Cage used chance operations and a time log to generate the content of the opera.

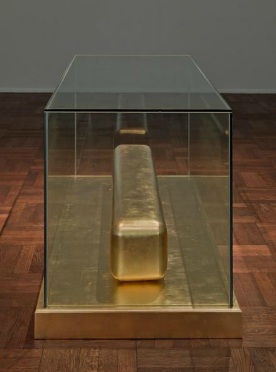

And this, apparently, is where Goebbels’ otherwise extraordinary production falls short. I’ll try to account for the differences—or more precisely, the changes—between Goebbels’ version and Cage’s, the immediately apparent one is his replacement of simple, graphic flats with actual operatic sets. Buening sees this as too deterministic, too willfully absurdist [in the mold of Robert Wilson, who, inexplicably, is the Triennial’s English talking head for Europera], and stuck to the cliches and one-liners of operatic theatricality. And too much of the director’s own indulgences, which runs diametrically counter to Cage’s purging intentions.

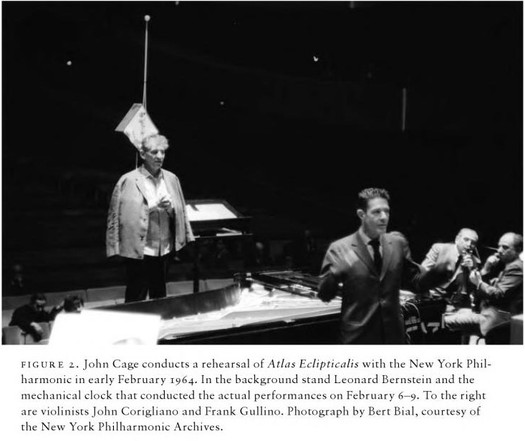

It’s a perennial problem with Cage’s interpreters, who take the indeterminacy of his compositions as license to do whatever they want. Not coincidentally, that sounds like exactly the criticism voiced in OMM by Sebastian Hanusa over the previous production of Europeras 1 & 2 at the Hannover State Opera. [It opened in October 2001, and I confess, I was not paying much attention to German opera gossip at the time.] According to Hanusa, Lowery kept the aria singers offstage, and instead of the chance-derived staging, he created various storytelling set pieces. It sounds almost as bad as Cage’s sabotaged NY Phil debut in 1964.

But it’s better than nothing? I don’t know. Is it the kind of thing you can watch on DVD? Will Europeras ever be staged in the US? [YES, SEE BELOW.] Frankly, we may still not be ready for it. Or maybe we’ve superseded it; with the right code and a few browser tabs on YouTube, we can generate our own Europera anytime we want. Man Bartlett’s #12hPoint, I’m looking at you.

UPDATE/CORRECTION: Thanks to DJW for correcting me; Europeras 1 & 2 was staged in the US. Christopher Hunt brought the original Frankfurt production to Summerfare at SUNY Purchase in 1988. According to John Rockwell’s bemused NY Times’ review, the New York version, which took place on a grander stage, was actually closer to Cage’s original vision, which the Frankfurt Opera had to rework after its main theater was damaged by arson just before the Europeras‘ premiere. Anyway, more to come on that.

* OK, the 639-year-long organ performance of As Slow As Possible, also from 1987, at St. Burchardi church in Halberstadt is also pretty grand. But I’d argue its grandeur is more the performance, not necessarily the composition.

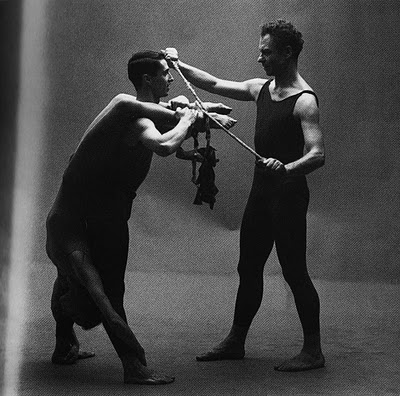

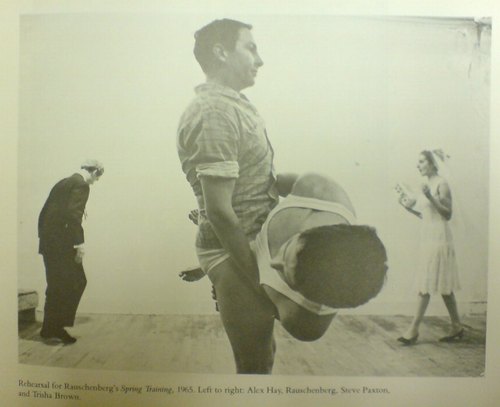

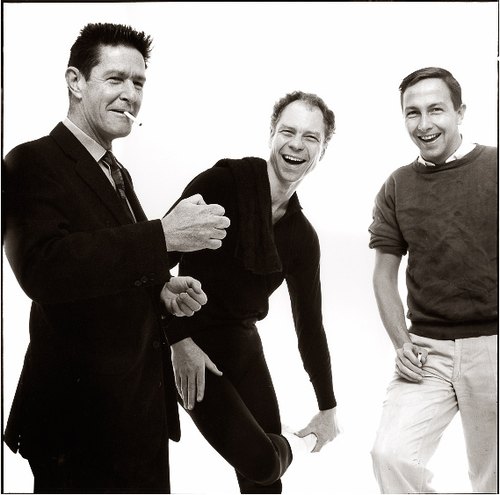

In 1958, Cage had performed at a blowout retrospective concert organized by Johns, Rauschenberg, and h

In 1958, Cage had performed at a blowout retrospective concert organized by Johns, Rauschenberg, and h