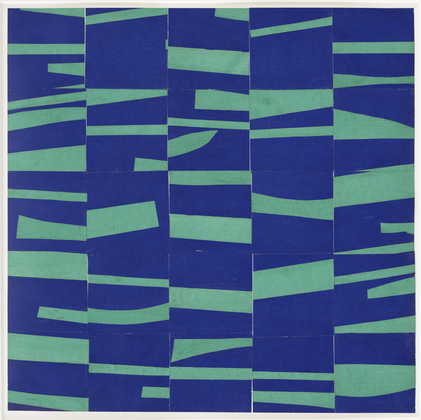

ce ci n’est pas un Razzle Dazzle? Ellsworth Kelly, Study for Meschers, 1951, moma

When tiny scans of Gwyneth Paltrow’s Interview interview with Ellsworth Kelly first appeared on tumblr, the only thing you could read was his pullquote about his tour of duty in World War II:

I was in what they called the camouflage secret army. The people at Fort Meade got the idea to make rubber dummies of tanks, which we inflated on the spot and waited for Germans to see.

Which, nuts, right? I guess I’d heard of Kelly’s camouflage involvement before, and I remembered somewhere that Bill Blass had also been in a camouflage division, but I’d never put it all together that these guys were in the Ghost Army, whose operations remained largely classified and unknown until the mid-1990s.

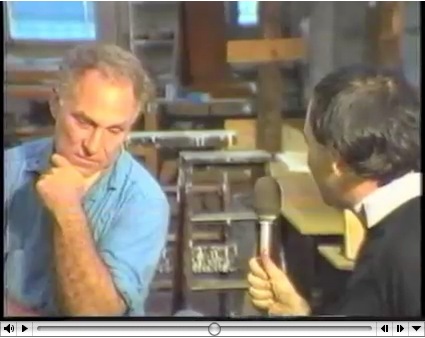

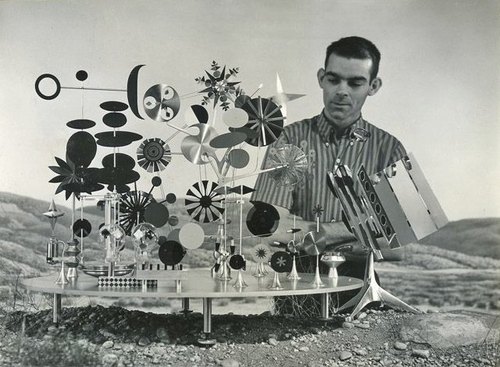

Here is Kelly’s fuller quote, and his photo of himself standing next to a burlap jeep:

PALTROW: Did you design camouflage while in the army?

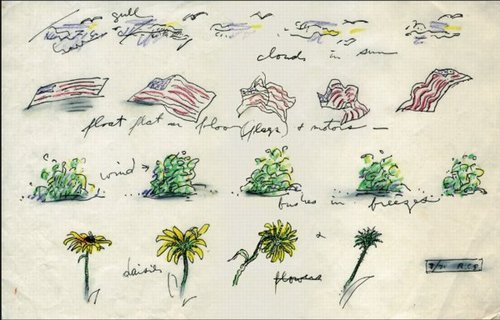

KELLY: I did posters. I was in what they called the camouflage secret army. This was in 1943. The people at Fort Meade got the idea to make rubber dummies of tanks, which we inflated on the spot and waited for Germans to see through their night photography or spies. We were in Normandy, for example, pretending to be a big, strong armored division which, in fact, was still in England. That way, even though the tanks were only inflated, the Germans would think there were a lot of them there, a lot of guns, a whole big infantry. We just blew them up and put them in a field. Then all of the German forces would move toward us, and we’d get the call to get out quick. So we had to whsssh [sound of deflating] package them up and get out of there in 20 minutes. Then our real forces, which were waiting, would attack from the rear.

PALTROW: So in a way, it was just like an art installation! That’s amazing.

KELLY: One time, we didn’t get the call and our troops went right by us and met the Germans head on. Then they retreated, and they saw our blow-up tanks and thought they were real and said, “Why didn’t you join us?” So, you see, we really did make-believe.

PALTROW: It’s the perfect job for an artist in combat.

KELLY: We even had the tank sounds magnified because tanks would go all night long.

It sounds like Kelly was actually in the 603rd Engineer Camouflage Battalion, one of four units in the 23rd HQ Special Troops, which entered France just after D-Day and ended up seeing quite a bit of action, all with balloons and loudspeakers instead of actual weapons.

As Edwards Park explains in a fairly detailed history, the 23rd’s main objective was to impersonate various active divisions in order to cover or obscure troop movements. The inflatable weaponry was designed to fool aerial reconnaissance, but the 23rd also acted out the operations of the units they were impersonating/replacing, visiting fake garbage dumps, and laying fake tank tracks at night under the cover of pre-recorded troop sounds and fake radio broadcasts. And they created fake badges and mingled with local civilian populations, passing along disinformation. As Park puts it, “It wasn’t long, in fact, before the 23rd had a voluminous file on visual identifications and the men suffered many a bloody finger sewing bogus shoulder patches on their uniforms before going into action.”

It’s one of many not-too-thinly veiled references to the 23rd’s apparently fruity reputation. I’m sure there’s at least one queer studies dissertation out there on masculinity, war, and the confluence of camouflage, artsiness, and passing for “real” soldiers.

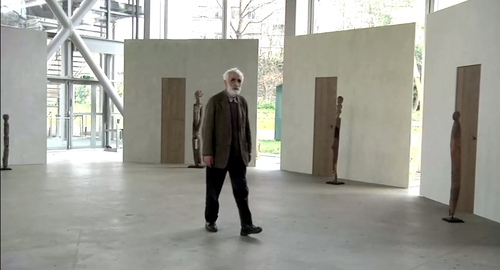

As NPR reported in 2007, most camo/deception soldiers were apparently ordered never to discuss their wartime efforts. But Jack Masey was never told to keep quiet–waitaminnit, Jack Masey? The USIA design director and serial Expo geodesic dome commissioner? Holy smokes! It all makes filmmaker Rick Beyer’s documentary Ghost Army feel like a race against time. I hope he got some good stuff.

Meanwhile, I guess I’m on the hunt for some 23rd material myself. In 2004, Sasha Archibald wrote in Cabinet about the Ghost Army’s unauthorized insignia for itself, which featured the three-legged triskelion and the motto, DECEIVE TO DEFEAT. [Christoph Cox’s excellent history of sonic deception in the military leads me to believe that everything I knew about the 23rd I learned in Cabinet Magazine.]

And I guess it’s too optimistic to imagine any rubber tanks or vintage camo have survived all these years; I can’t imagine if the top secret thing preserved such artifacts or doomed them. But at the least I could start tracking down some of those Ellsworth Kelly posters.

OK, Meyers’ site points to this 1992 video by/about the WWII paintings of Harold Laynor, who describes himself as part of the “famous Ghost Army,” and says its activities were “unknown to the general public until well after 1980.” Hmm. Laynor also says there was an initial plan in 1942-3 for the 603rd to focus on domestic camouflage. But that the British successes with battlefield camo in North Africa inspired the US to deploy the deception unit in combat.

Related: British WWII bullshit camo stories

The Civilian Camouflage Council, included a lot of folks at Kelly’s school, Pratt

Sounds so-so, but full of facts/details: military historian Jonathan Gawne’s 2002 book, GHOSTS OF THE ETO: American Tactical Deception Units in the European Theater, 1944 – 1945

SS For “Ark, Chapter 10,” which was the three-person show you organized at the end of your time at Orchard, you made paintings that related to Orchard’s history, and displayed several of them on storage racks similar to ones you have here in your studio. The display of paintings became a sculpture [From One O to Another].

SS For “Ark, Chapter 10,” which was the three-person show you organized at the end of your time at Orchard, you made paintings that related to Orchard’s history, and displayed several of them on storage racks similar to ones you have here in your studio. The display of paintings became a sculpture [From One O to Another].