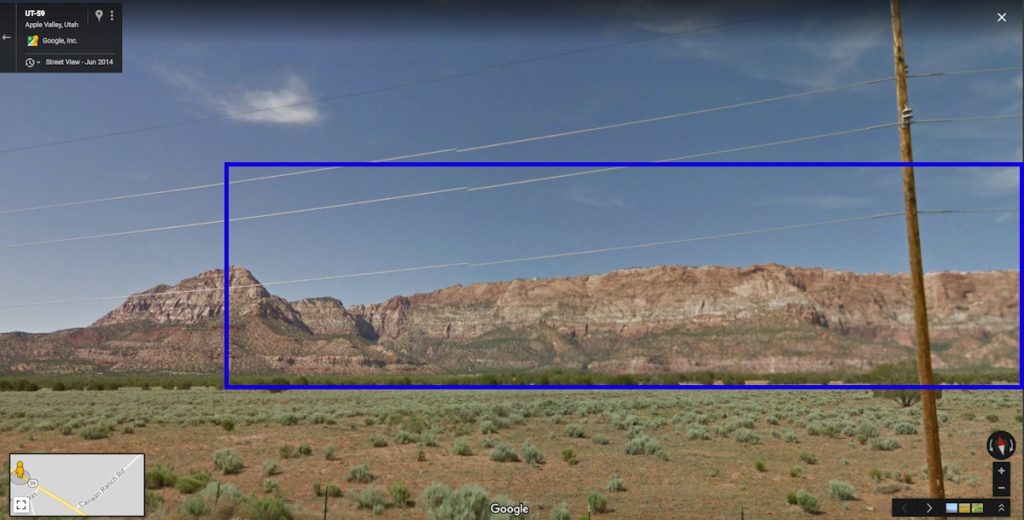

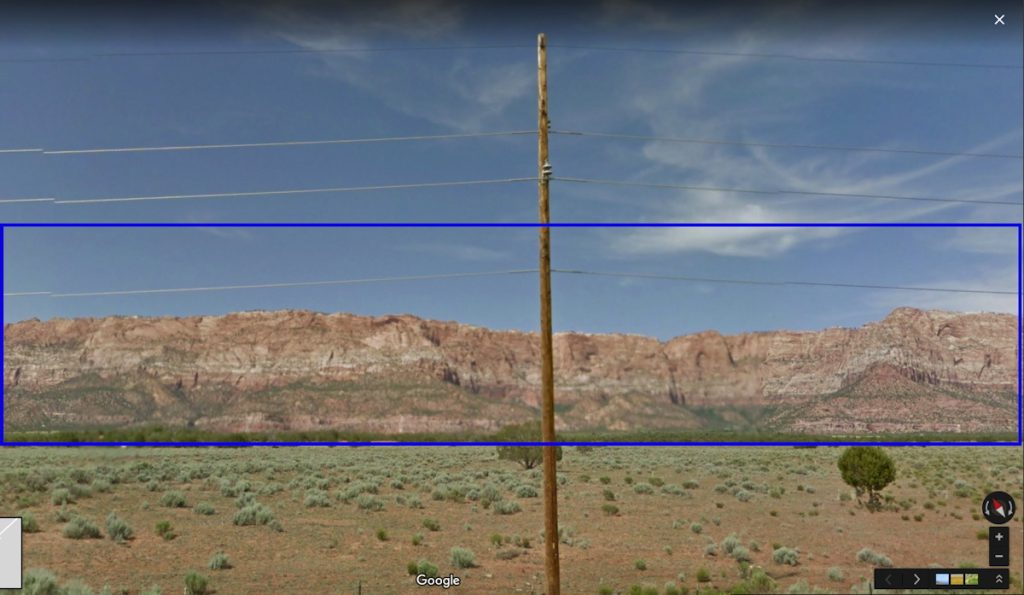

Each of the five elements in Tony Smith’s sculpture Wandering Rocks (1967) has a name: Smohawk, Shaft, Dud, Slide, and Crocus.

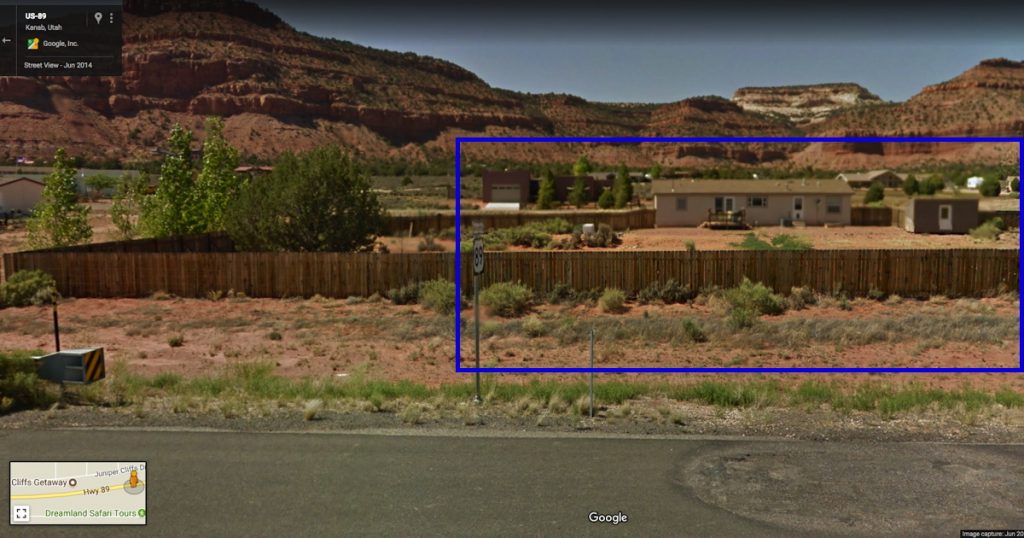

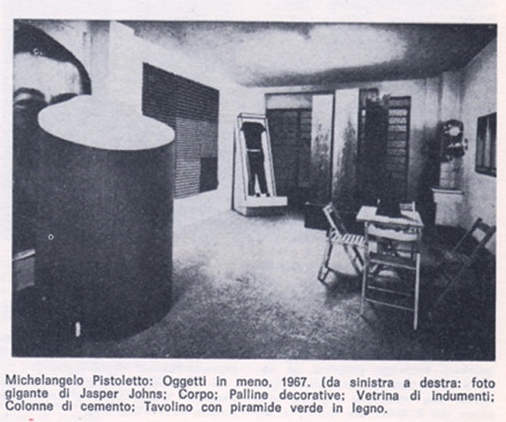

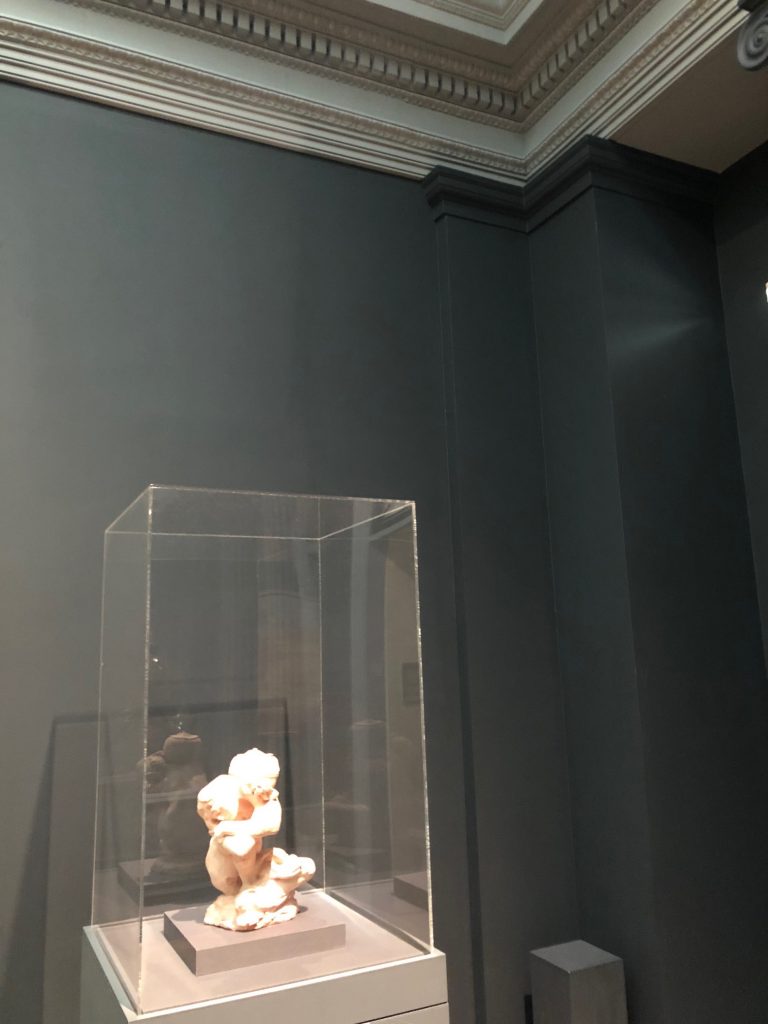

Of the edition of five, at least one Wandering Rocks is installed indoors. The National Gallery’s is on the lawn [above]. The Seattle Art Museum’s Olympic Sculpture Park’s, which is the artist’s proof, was previously installed on and around a woodchipped path [below].

Wandering Rocks has since been moved.

This installation seems a deliberate mockery of the plaque at the OSP, which is a quote from Smith:

What is my intention? It is a new measure of man, in forms of free space, in terms of space that is defined but not enclosed, in terms of measurable space that flows so subtly into the infinite that it is impossible to know where the boundaries of art and nature lie…”

Placing art is hard. Placing sculpture in public is harder still. So many decisions can detract from the experience of art, or can thwart the artist’s intentions. With close looking and self-awareness, it is often possible to overcome these environmental obstacles and appreciate what the artist has accomplished. Additional benefit can be gained by understanding what the curator’s intentions might have been, too, whether or not they achieve them.

For the experienced art viewer, it is a special challenge to appreciate the work and understand its context while identifying the flaws, errors, or shortcomings that mar its presentation. A wonky spotlight. No benches. Audio bleeding from the video installation two galleries away. One or two of these, we can let slide. When such seemingly avoidable distractions pile up, though, and threaten to ruin an art experience, perhaps a conceptual artistic exercise can help.

To deal with unnecessarily problematic encounters with art, I propose to turn the third most egregious or annoying thing about it into a new work of its own. It may not solve the problems you identify, but maybe you’ll get some relief from art’s power to give significance and meaning to your annoyance. Maybe the thrill of discovering installfails and the interpretative exercise of ranking them will become a reassuring relief, if not a delight, when you look at art.

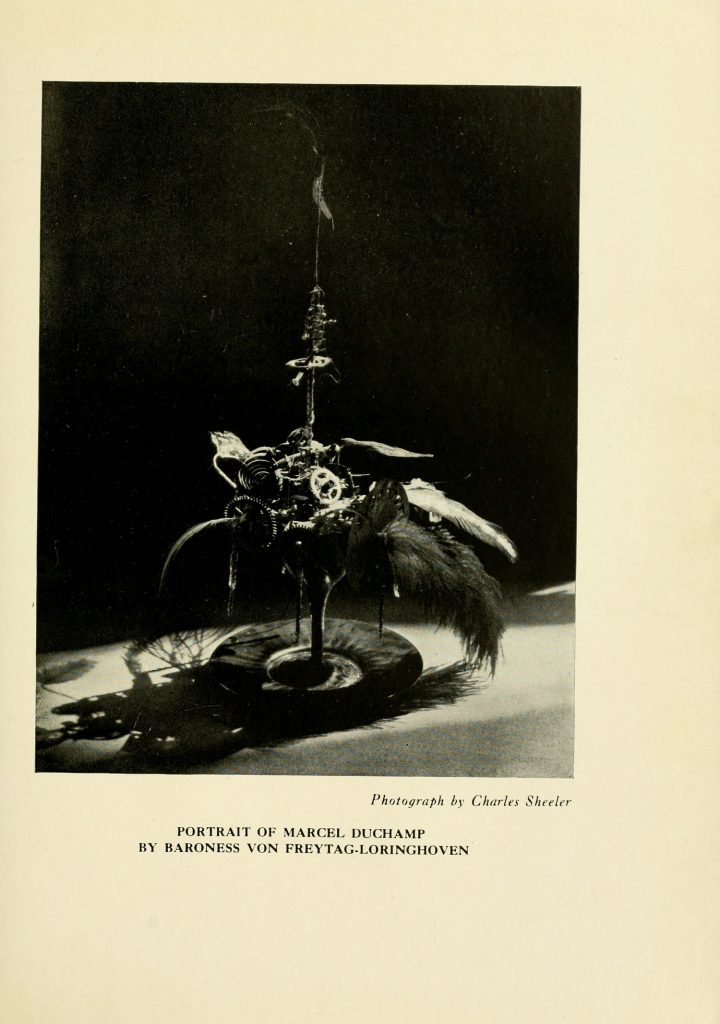

the creative act is not performed by the artist alone; the spectator brings the work in contact with the external world by deciphering and interpreting its inner qualifications and thus adds his contribution to the creative act.

Wrote Duchamp, who could not have imagined a work whose form–indeed, its entire existence–is predicated on the spectator’s decision to conjure it through affront.

Now, I don’t want to uncritically gamify your museum visits. Being compelled to contemplate an artwork about your connoisseurship of annoyance could become infuriating if it begins to intrude on. Every. Freaking. Poorly glazed. Painting. In the place. But it could also lead to an awakening, a liberation from the burdens of the imperfections of the external world, which in turn fosters deeper encounters with the art in front of you. Deciding not to conjure the work by deciding not to log more than one or two annoying things in an encounter is a valid, and powerful, option.

And so in honor of the eagle-eyed spotting of the sprinkler cover sitting in the lawn next to Wandering Rocks, between the otherwise unremarked-upon stanchions and the steel cheese grater fence, I have designated this work Untitled (Avoidable).

May it be ever at your service. Send pics.

Previously, slightly related:

On Tomason, or the flipside of dame architecture

Tomasons and Akasegawa Genpei, translated

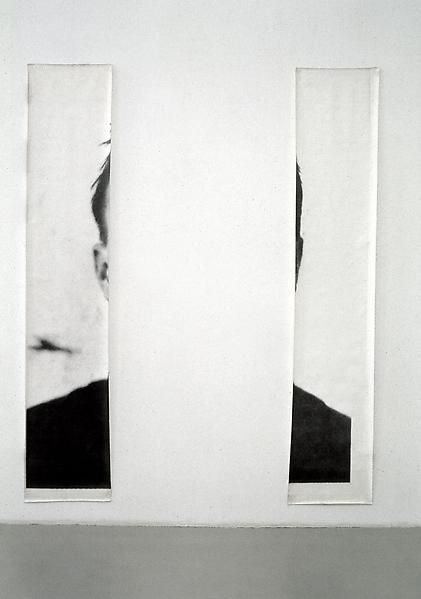

Speaking of painting, the Proposte monocrome, gris has been accepted. I’m not sure I agree with the choice, but it was really out of my hands.

Speaking of painting, the Proposte monocrome, gris has been accepted. I’m not sure I agree with the choice, but it was really out of my hands.