In response to Olia Lialina’s post last week about screwy reproductions of her c.1996 lo-res digital imagery, Cass Fino-Radin writes about how Rhizome deals with archiving and documenting digital art in its native formats, platforms and resolutions: by photographing it.

This very issue of how low-resolution digital images gum up the hi-res assumptions our visual systems are built on is was one of the unexpectedly central discoveries of making Untitled (300 x 404) project. Though initially, at least, the losses and distortions of moving a thumbnail-sized jpg through the media channels were for me evidence or symbolic of the information that’s lost through ridiculous copyright restrictions, and not so concerned with archiving or perpetuation.

But that’s not important right now. Because just a few days before reading about Fino-Radin’s archival challenges, I stumbled across another data-driven use of old-school photography, on Project Echo.

I just received a rare print copy of the 1961 Bell Systems Technical Journal devoted to Project Echo, which has a dozen papers reporting Bell Labs’ findings and processes of tracking and operating an inflatable, reflective communications satellite. What’s extraordinary about the papers is what’s always fascinated me about the Echo satelloons in the first place: they were analog experiments done largely by hand, and before computers were practical tools for real-time tasks.

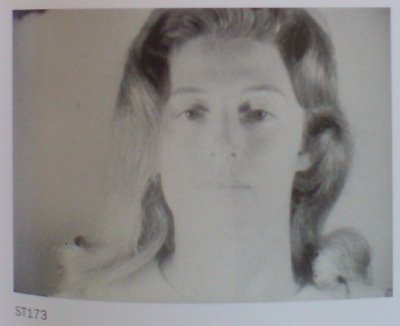

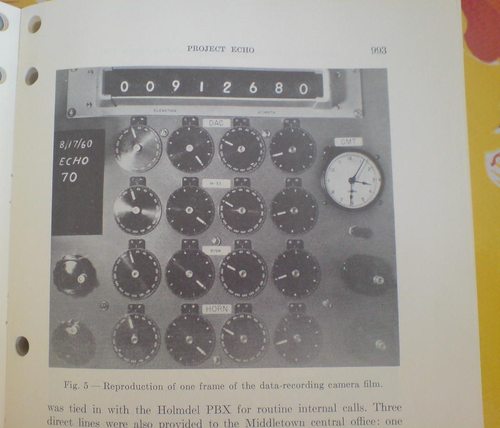

And so, for example, in order to record all the satellite tracking data and readouts at the Holmdel, NJ receiving and transmission station, they took pictures of the control panel. Here’s the description from Bell Labs project engineer Dr. William C. Jakes’ paper [available from dtic.mil as a pdf]:

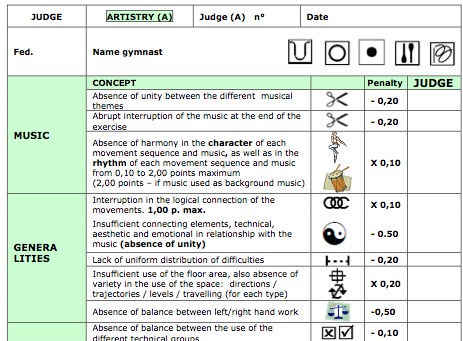

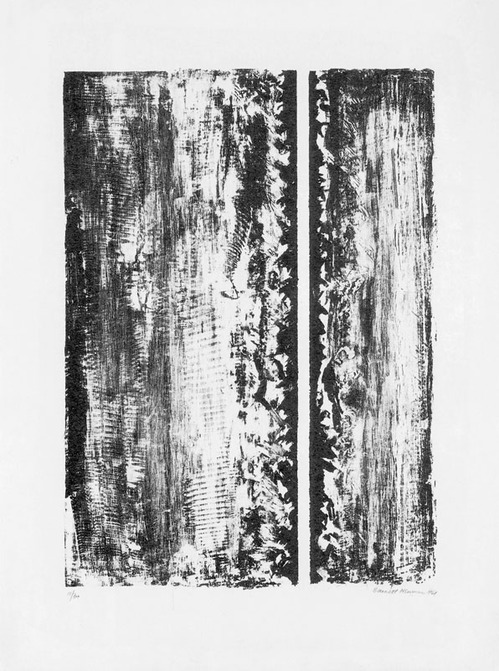

In order to have a record of the positions of the various moving elements of the system during a satellite pass, each element was provided with synchro read-outs which were periodically photographed. Pictures were taken at one-second intervals of a panel carrying the two-speed azimuth and elevation position dials for the DAC, M-33 (optics), 60-foot dish, and horn antenna. A Greenwich Mean Time clock also appeared in the photographs. Position angles could be read to +/- 0.01 degrees, and time to 0.5 second. An enlargement of one frame of such a record is shown. [above]

But wait, there was more:

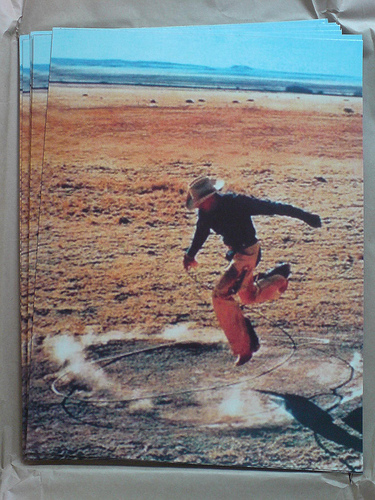

The 60-foot dish and horn antennas were each equipped with a bore-sight camera [!] that could be started at will whenever the satellite was visible. Pictures were taken at four frames per second, and included a reticle for indicating angular offsets to an accuracy of +/-0.01 deg. and a time-coded counter.

I have contacted archivists for Bell Labs, and unfortunately, no such operational film records have survived. In the company’s possession, anyway. But I am still looking.