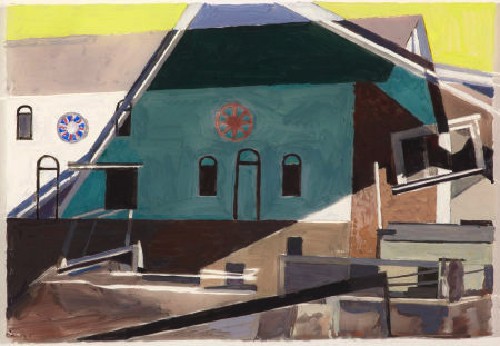

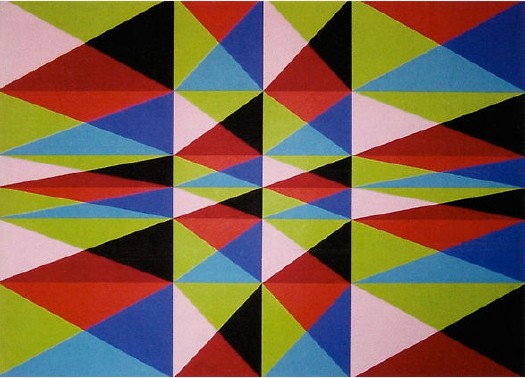

You never know what’ll turn up. In the same sale as that Sheeler study is this 1965 geometric abstract painting by Dean Fleming, one of the pioneers of SoHo. In 1962, Fleming founded the Park Place Gallery, an artist co-op, with a small group of other artists, including Mark diSuvero, Frosty Meyers, and Robert Grosvenor. Their first gallery director was John Gibson, and their second was Paula Cooper. Park Place was the first gallery in SoHo [though technically, it was north of Houston on LaGuardia Place], which made it basically the first center of the New York art world that emerged in the 1960s.

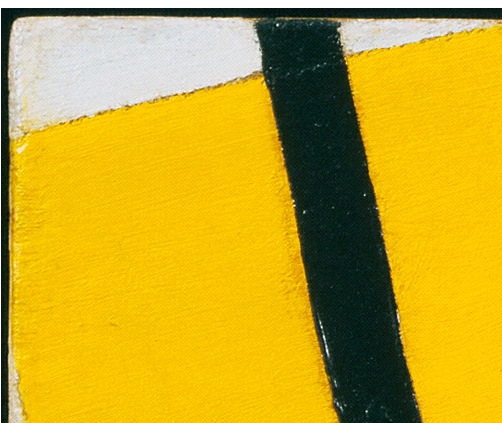

By 1966-7, Fleming was feeling burned out on the art scene/market. As he told Michael Fallon in 2005, “In New York I was the ‘parallelogram’ painter, which I thought sucked beyond belief.” Well, I’m sure no one wants to sit around taping paint edges day in and day out to meet the uptown demand [detail below], but it sure looked great while it lasted.

Fleming’s early 1960s abstraction is proto-minimalist, proto-op-art, a bit of East Coast Hard Edge, if there was such a thing, basically resistant to the canonical categories of 1960s New York as we’ve received them.

Last year, Linda Dalrymple Henderson curated a show about the Park Place Gallery artists at UT-Austin’s Blanton Museum. Here’s a quote Sharon Butler pulled when she blogged about the show that kind of brings it all home:

“Park Place artists were united by their multifaceted explorations of space. Their abstract paintings and sculptures, with dynamic geometric forms and color palettes, created optical tension, and were partially inspired by the architecture and energy of urban New York. The group regularly discussed the visionary theories of Buckminster Fuller, Space Age technologies, science fiction, and the psychology of expanded perception, and these ideas become essential to their work. Dean Fleming’s paintings of shifting, contradictory spaces were intended to transform viewers, provoking an expanded consciousness. Di Suvero’s allegiance was to Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, and his kinetic sculptures explored gravity and momentum in space.

Buckminster Fuller? No wonder the show looks like The Future. It’s like going simultaneously forward and backward in time. [Here’s a smaller slideshow with bigger images than the truly tiny UT-A site. The parallelogram in the background is the second-best Fleming painting in the show; Lime Line, also from 1965, looks like a perfect companion piece to the square Untitled.]

Fleming’s got a shed full of 50 years of work out back of his 40-foot geodesic dome studio at Libre, Colorado, the artists community/commune he co-founded in 1968. I have no idea what his current stuff looks like, but this sweet example from a fascinating, seminal center of activity that’s long overdue for re-examination looks like a steal.

Lot: 67085: Untitled, 1965, Dean Fleming, acrylic on canvas, 32×32 in. est $1,200-1,600 [ha.com]