I know it’s folly to take auction catalogue text as art history, but it is of a piece, at least in this case.

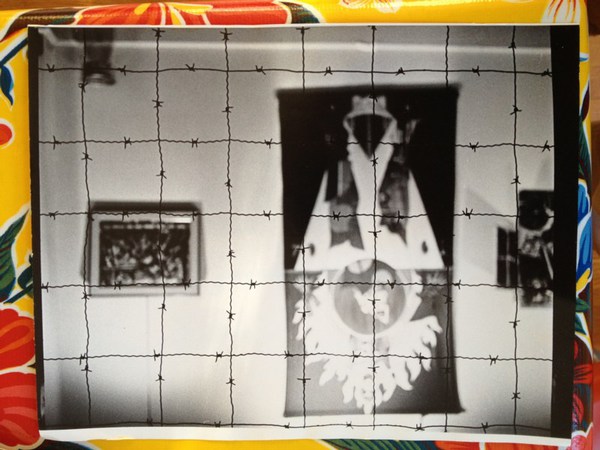

Untitled, recto, 1954, Collection Paul Taylor, image: Sotheby’s

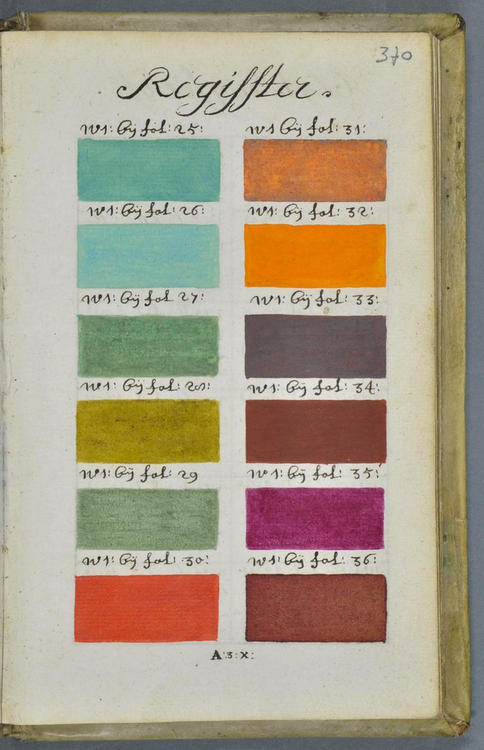

Last night’s sale at Sotheby’s included a very early, underdocumented 1954 combine by Robert Rauschenberg, which he gave to the dancer and choreographer Paul Taylor a decade later. [I say underdocumented because I can’t find any mention of it in Paul Schimmel’s otherwise exhaustive Combines catalogue, or anywhere online not associated with the auction.]

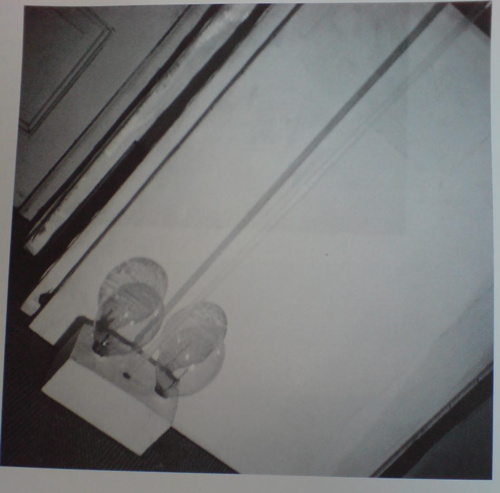

Untitled, verso, 1954, Collection Paul Taylor, that polka dot fabric turns up on at least six other combines, including Short Circuit, image: Sotheby’s

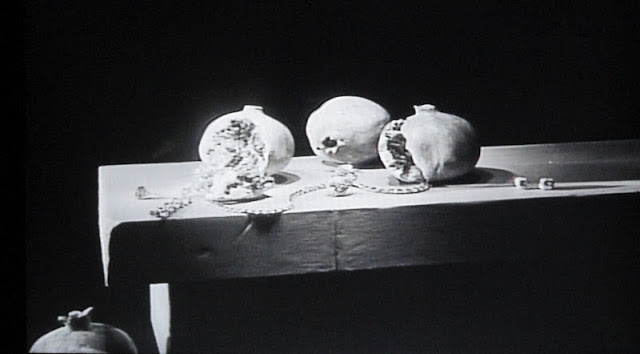

The piece is freestanding, tabletop-size, with a double-sided painting/collage mounted on what seems like a 2×4 wood base. There’s a lightbulb sandwiched in between the support slats, and a pair of radiometers, those little gadgets with black & white panels that spin when exposed to light.

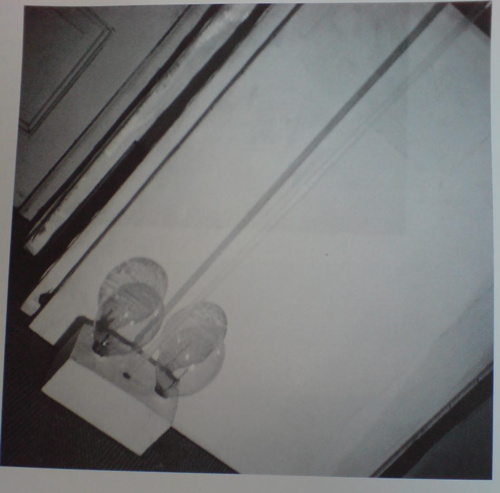

The Man With Two Souls, 1950, photographed by Rauschenberg in 1951 in his UWS apartment, where Twombly told Walter Hopps he’d seen it. He later got it. image: Hopps’s Rauschenberg: The Early 50s

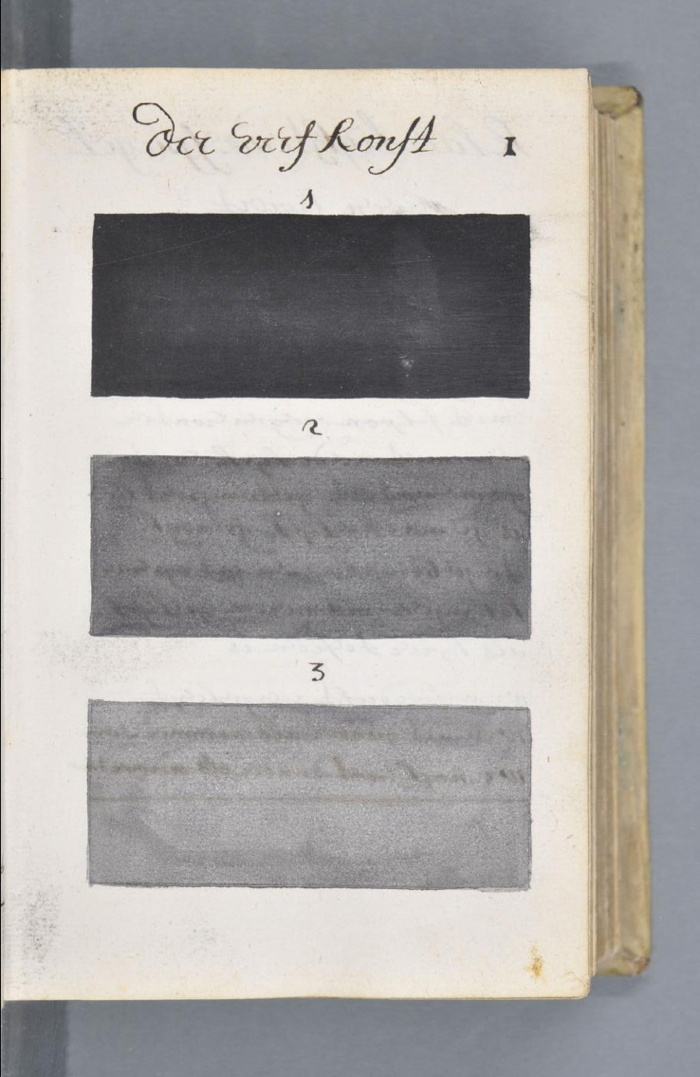

As soon as I saw it, I thought of Rauschenberg’s earliest surviving sculpture, made in 1950. Cy Twombly got it after Rauschenberg’s 1951 show at Betty Parsons, but before he and Bob took off for seven months to Africa, leaving Susan Weil and the baby behind. The piece is called The Man With Two Souls, and it consists of a glass rod flanked by a bulbous pair of wine bottles inserted in a cast plaster block. Charles Stuckey suggested it was an homage to Barnett Newman’s sculpture Here I, which was shown at Parsons earlier in 1951. Yes, that might be one allusion.

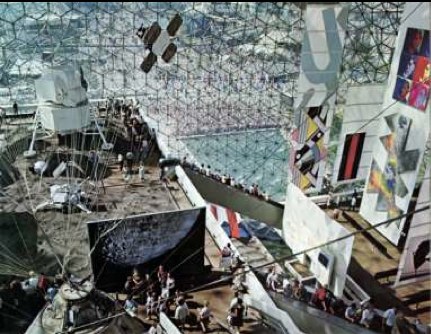

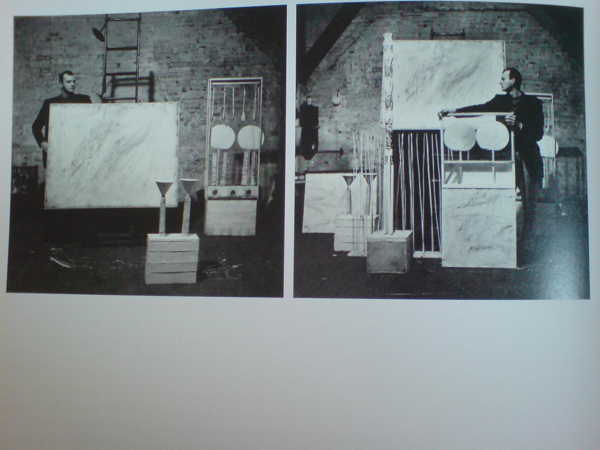

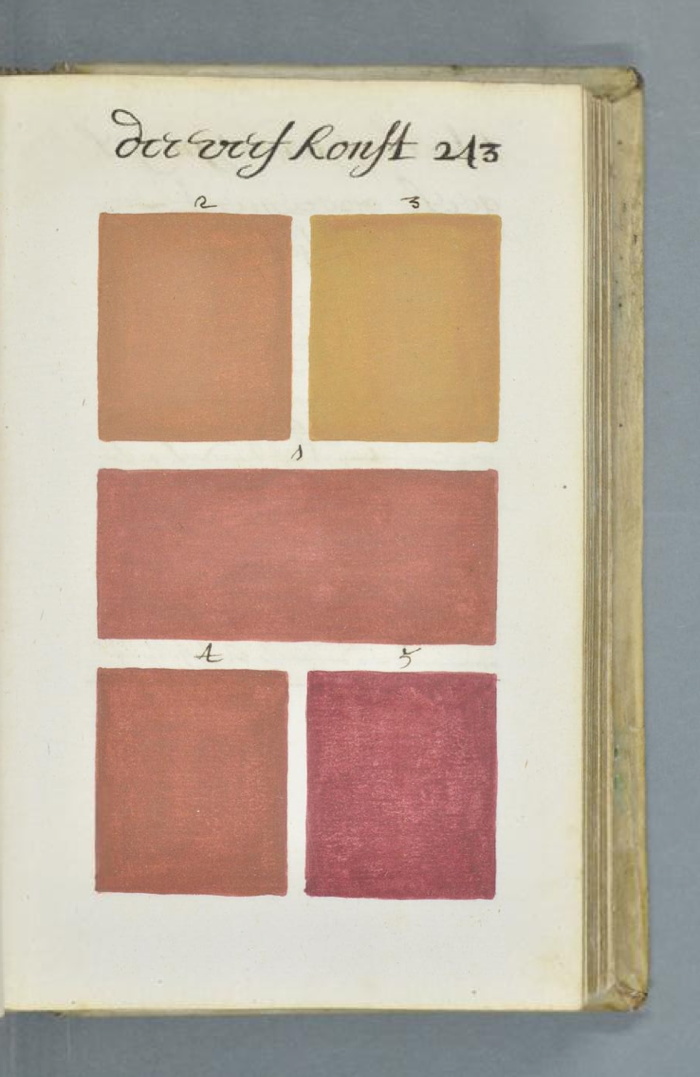

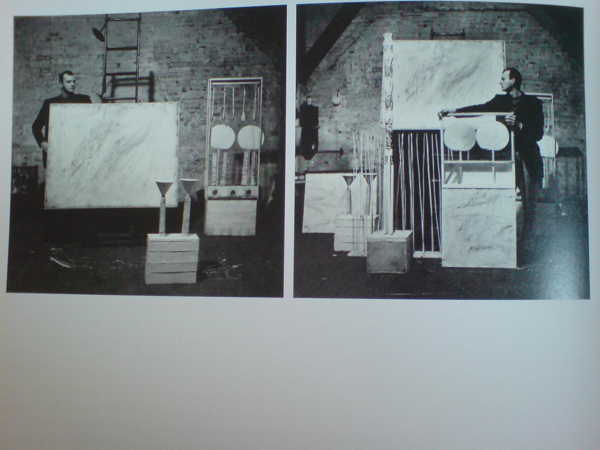

Twombly and sculptures in Twombly’s studio, 1954, photographed by Rauschenberg, image via Schimmel’s Combines

It also might be similar to almost every Cy Twombly sculpture in these photos Bob took in 1954, the year Taylor’s combine was made. The year, in fact, when Rauschenberg made what’s considered the first of his combines, set pieces for Taylor’s debut as a choreographer after leaving Merce Cunningham’s company in mid-1954.

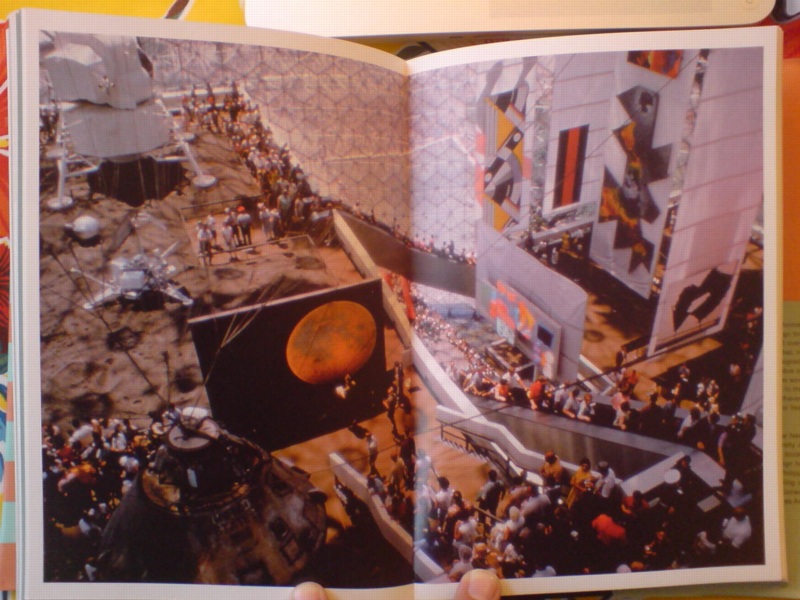

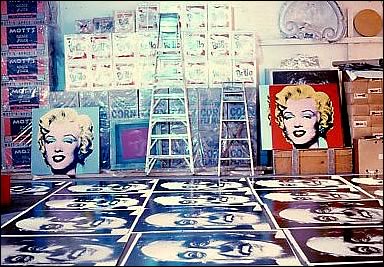

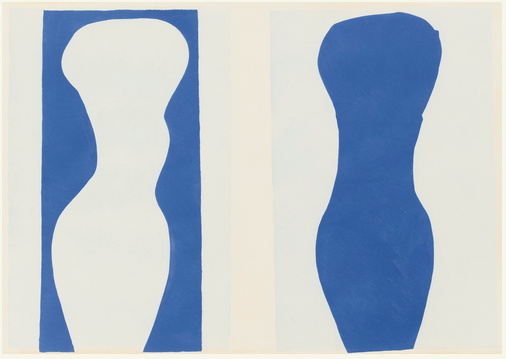

And depending on which side you’re looking at, Taylor’s piece looks an awful lot like Minutiae, the free-standing set piece Bob made for Merce’s December 1954 performance at BAM. Which is all set up for my complaint about Sotheby’s catalogue text, which acknowledges that Rauschenberg was “informed by the influences” of his contemporaries like Jasper Johns, and then immediately distances the two artists:

Though their practices were fundamentally at odds, both conceptually and aesthetically, the two men supported each other’s stylistic experimentation during this critical time of immense growth and evolution.

Unfathomable difference has been the starting point of any discussion of Rauschenberg and Johns’ early work since at least 1963, when Allan Solomon gave them each one-man shows at the Jewish Museum. It’s a presumption of separateness that shuts off any exploration of similarity, much less exchange or collaboration. And especially in the case of Rauschenberg and his artist/partners, it heads off any questions of joint creation or shared authorship.

Minutiae, made with help from Johns in time for Merce Cunningham’s Dec. 7 1954 performance at BAM

Johns has said publicly he worked on Minutiae. Twombly drew on Rebus and who knows what else. Johns even said he made a Rauschenberg with Bob later signed, and that he came up with the term “combine.”

But whether it’s historic or persistent institutionalized homophobia, emotions & ego, the demands of the market, or the lone genius paradigm of the times, it’s apparently still impossible to ask if there are similarities or connections between these artists’ contemporaneous work.

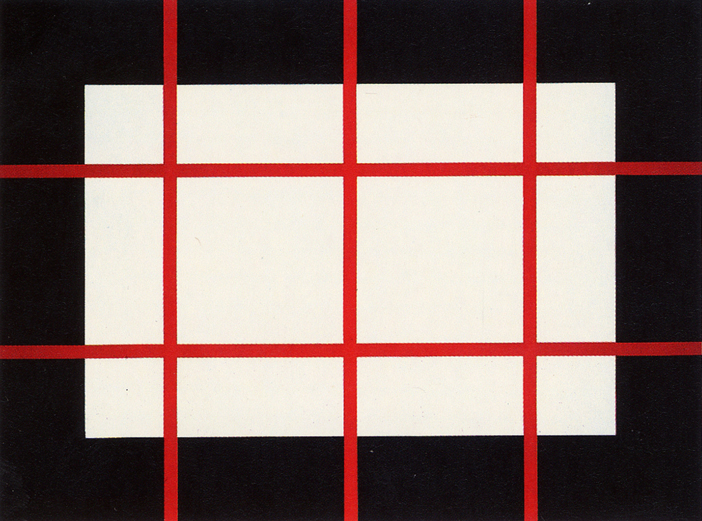

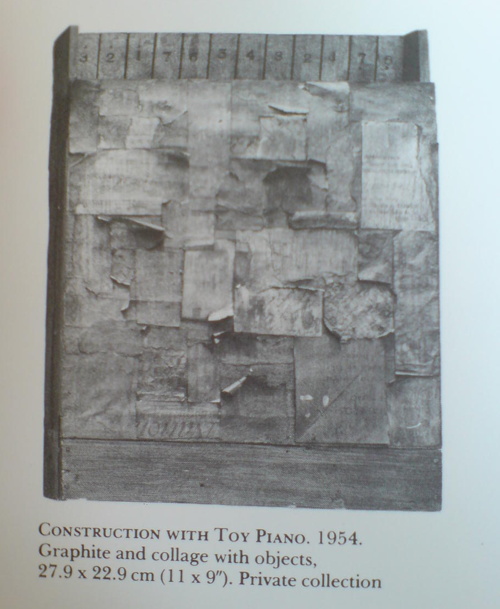

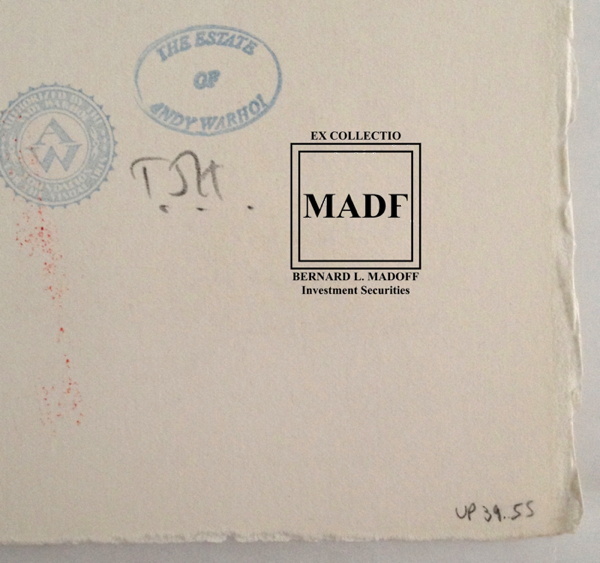

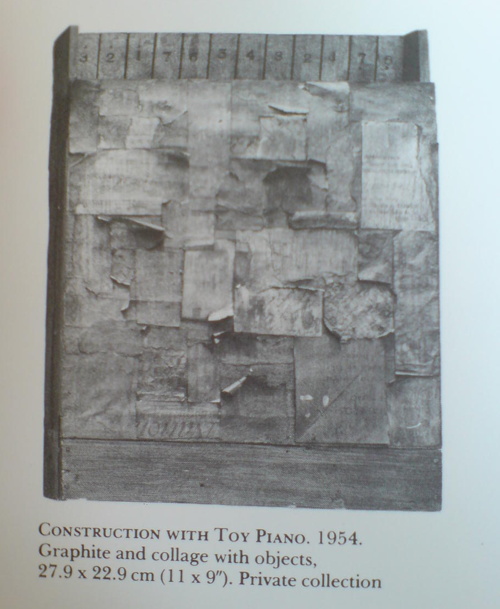

Construction with Toy Piano, 1954, image: Michael Crichton’s Jasper Johns

Twombly and Rauschenberg are both gone, alas, and Johns doesn’t seem too interested to elaborate, seeing as how he has systematically hunted down and destroyed his own work from before 1955. But at least one piece that survives, Construction with Toy Piano, a book-sized wooden object covered with painted collage, looks like it could have been made in the same room as Paul Taylor’s combine, if not by the same mind or hands. Just asking the question.