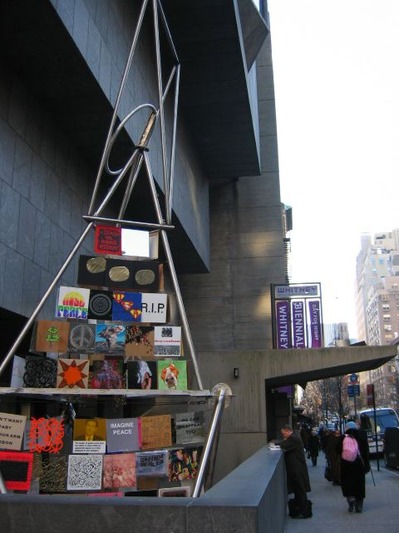

Punishment Park? How did I not know about Peter Watkins’ incendiary 1971, anti-war, anti-fascist, faux-news documentary? I mean, it was the movie Rirkrit chose to broadcast on his unlicensed TV station in the Guggenheim. I sat in Anthology’s rickety seats for the entire 5+ hours of The Commune (Paris, 1871). Is it one of those things that just looks so completely, unrecognizably different in the light of Occupy Wall Street, that–no.

When Punishment Park was finally released on DVD in 2005, it was the peak of a globally unpopular war, which was tainted by torture, unlawful detainment and military tribunals, violations of basic constitutional and human rights, and polarized rhetoric within American culture. So no, I don’t think I registered what Watkins had done.

Which, holy smokes. Here’s how Holland Cotter describes Punishment Park in his 2005 review of Rirkrit’s show:

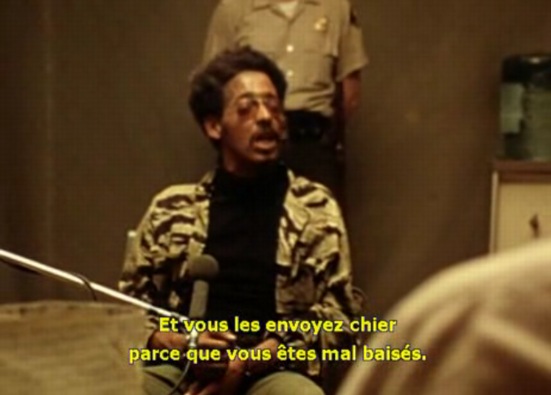

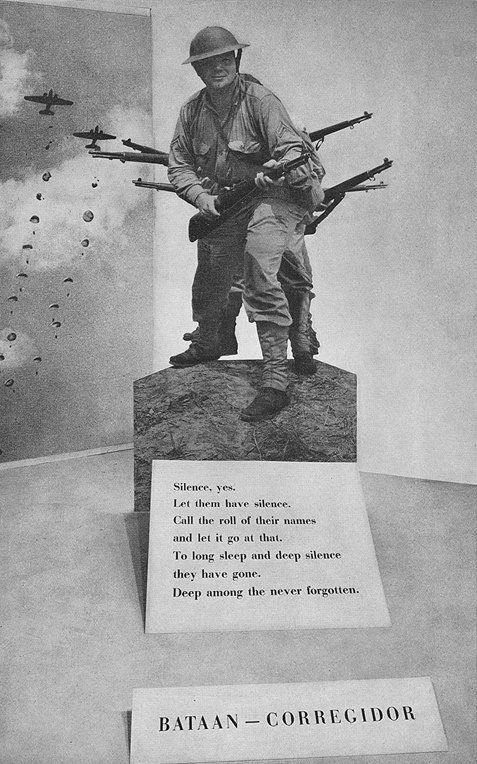

it is a docudrama about the brutal silencing of antiwar protesters during the Vietnam period. Many of the actors were amateurs. The people cast as activists were, in fact, real-life activists; the police were played by former police officers.

Their lack of theatrical training gives the film a curious tension, making it seem both authentically documentary and stagy. It feels something like that era’s political street theater, which was cropping up all over the United States and Europe at a moment when anger and paranoia were at flood tide. This aesthetic certainly suits the low-tech character of the broadcast facilities, which are pretty rudimentary.

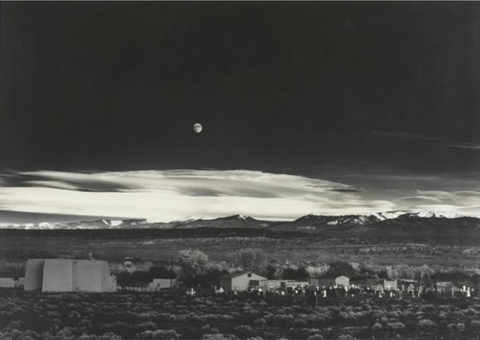

Shooting in an army tent and the Mojave Desert, a British news crew follows two groups of activists/protestors as they are run through a sham tribunal and are given the choice between excessive federal prison sentences and an impossibly brutal three-day race across a vast desert reservation, aka “Punishment Park,” where they are hunted down by National Guardsmen training for the next Kent State.

It’s like Predator and The Tenth Victim gave birth to the sequel of Zabriskie Point, starring the Chicago Seven. It is not pretty.

Punishment Park may not be a great movie, but it is definitely a fascinating one, one which is difficult to watch, and apparently difficult to like. I think that’s by design, though; it seems calculated to antagonize and/or enrage basically anyone with a political opinion and a stake in the outcome of the American experiment. It deserved a little more credit than it got, though, and certainly better consideration than Vincent Canby was capable of:

Because all literature, including futuristic nonsense like this, represents someone’s wish-fulfilling dream, I can’t help but suspect that Watkins’s cautionary fable is really a wildly sincere desire to find his own ultimate punishment.

Yow.

The freaky thing, I guess, is the way Punishment Park manages to both over- and under-predict the cultural rifts and abuses of power in American politicized culture over the intervening 40 years. I think had I seen Punishment Park in 2005, I would have distanced it as a historic, histrionic artifact. But given the last few years/months/weeks, I can’t help but see parallels and hear echoes between the film, its time, and today.

The other, less uncomfortable thing–I mentioned Zabriskie Point for a reason–is how Punishment Park alters the context of the 60s and 70s for me. I can’t help but see the counterculture and the desert, the military and the desert, war and the desert, art and filmmakers in the desert, quite differently now.

The New Yorker Films DVD release of Punishment Park is available on Amazon and Netflix.

Serota delivers that question with an intensity that makes it feel like a scoop, and I don’t think his reaction is [just] for the camera. I haven’t found any previous mention of Family of Man either by Richter or in relation to his work. Steichen isn’t in the index for the collected writings. There’s no mention of it in

Serota delivers that question with an intensity that makes it feel like a scoop, and I don’t think his reaction is [just] for the camera. I haven’t found any previous mention of Family of Man either by Richter or in relation to his work. Steichen isn’t in the index for the collected writings. There’s no mention of it in