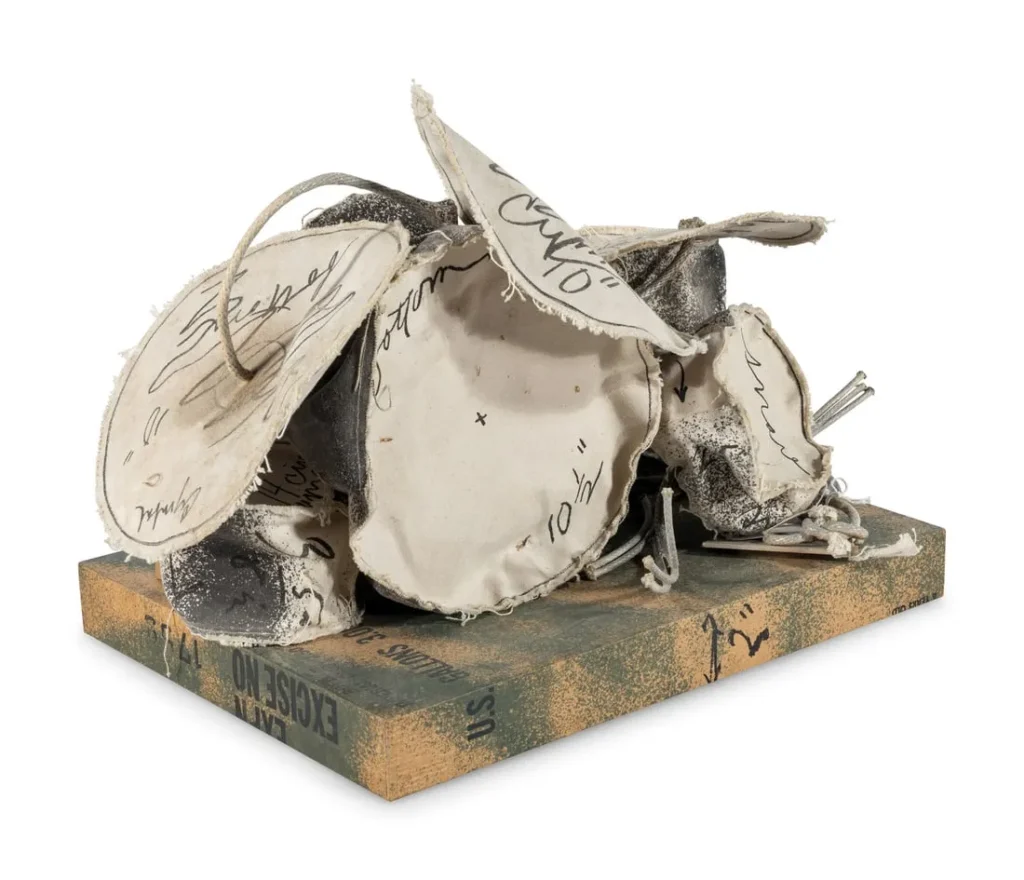

Thinking of Steve Roden took me back to a work he helped inspire: Untitled (George Washington’s Coffin). Steve had been “obsessed” by an auction photograph of two pieces of nondescript wood bound together, which turned out to be fragments of George Washington’s coffin. Turns out Washington was reinterred several times at Mount Vernon, and his heirs made a practice of giving away small pieces of his old coffin(s) to visitors. After wondering what this might have been like, living within this tradition of democratic relicism, I proposed to reassemble the coffin, reuniting all its pieces scattered to the world. This was in October 2016, if you can imagine.

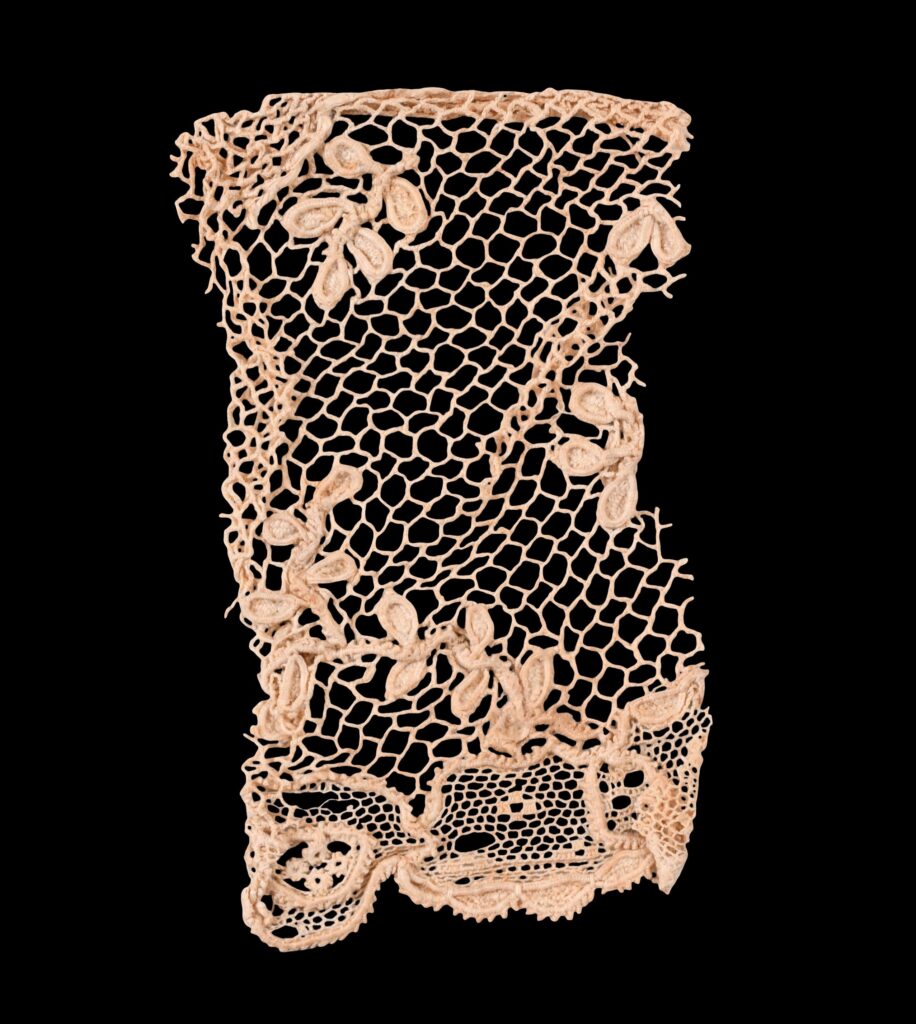

And then I found this: a 1 by 1 3/4 inch fragment of lace that once belonged to George Washington, and which was given by Martha Washington to Gilbert Stuart to aid in painting Washington’s portrait. The catalogue note says it was a gift in 1865 of Jane Stuart, the painter’s daughter, who was also a painter, and who had beef about lace with rival Washington portraitist Rembrandt Peale:

…Peale claimed he had never seen Washington wearing elitist lace “ruffles,” notably represented in Stuart’s portrait hanging in the White House. To counter Peale’s accusation and defend her father’s character, Anne Stuart replied, “We [have] in our possession some lace which my father cut from Washington’s linen. The circumstances were these: My father asked Mrs. Washington if she could let him have a piece of lace, such as the General wore, to paint from. She said, ‘Certainly,’ and did it make any difference if it were old. He replied, ‘Certainly not, I only wish to give the general effect.’ She then brought the linen with the lace on it, and said, ‘Keep it, it may be of use for other pictures.’ I have given away this lace an inch at a time, until it has all disappeared; the largest piece I gave to the late Mrs. Harrison Gray Otis, who had it framed.

And so again we have the propagation of relics of George Washington by those with the most intimate physical connections to him, and disputes over their political implications. In addition to contemporary correspondence about the president’s lace, Mount Vernon holds two similar fragments, and a third, or rather a fourth, is reported in the collection of the Dorothy Quincy Homestead in Quincy, Massachusetts.

While I wonder about these objects and the social and historical processes that produce and preserve them, I am not really in a reassemble George Washington’s old lace shirt as a conceptual project mood these days. So you may bid unimpeded (by me, at least. There are already five bids, though the reserve is not yet met.

The other lot in the two-lot sale is, amazingly, The Metallic Pegasus Judicial Collar from the collection of the late Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Maybe the buyer will part it out one silver bead or feather at a time to mark Ginsburg’s judicial legacy, until it has all disappeared.

[update: the lace sold for $3,250. The collar did not sell for $195,000.]

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s Judicial Collar & George Washington’s Gilbert Stuart Portrait Lace | September 21, 2023 [potomackcompany]