I was intrigued by Roy Lichtenstein’s Prop For A Film when it showed up last summer at Phillips in London. Obviously, the main thing was the work itself: a large [3.5 x 8 ft] abstract, shaped field of Ben-Day dots, pretty fantastic, actually, which turned out to be a beach. The other thing about it, also obviously, was hey wha? Lichtenstein made a film? A film he showed at both LACMA and the US Pavilion at Expo70 in Osaka?

I was already pretty fixated on several of these related topics at the time, so I started poking around on the story of Lichtenstein, his film–films, actually–and his Prop For A Film. It’s all pretty odd and interesting, and somewhat complicated, and though I started gearing up to write about it, I’ve kind of held off, or haven’t gotten around to it, I guess, for almost a year now.

But then today, I see that Andrew Russeth reported for the Observer that Prop For A Film, which failed to sell at Phillips last summer, has turned up in Sotheby’s New York contemporary sale next month, albeit with a much lower estimate.

And though Sotheby’s catalogue copy seems almost identical to Phillips’, they added a note that the Whitney will show Lichtenstein’s films in October, the first exhibition of them in over 40 years.

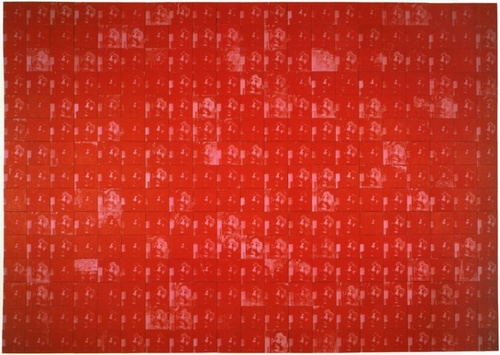

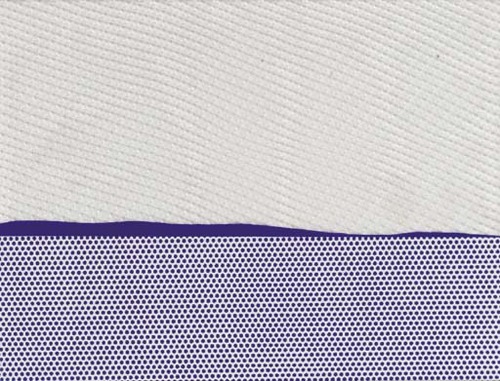

So yeah, Prop For A Film. To get right down to it, I’m not sure it’s really a painting. Which doesn’t mean it’s not a very interesting Lichtenstein.

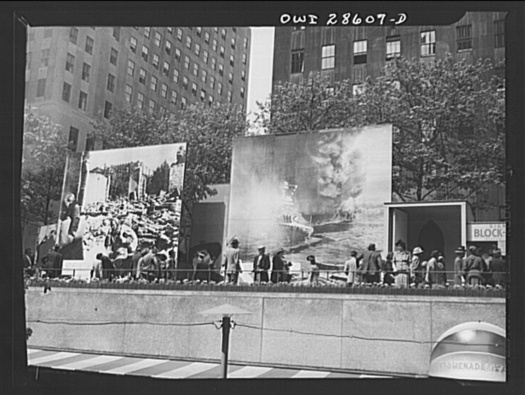

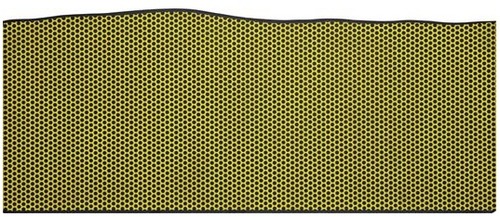

Starting around 1964, when the world was still trying to come to grips with the painterly implications of his print-related imagery and Ben-Day dots, Lichtenstein was already experimenting with other techniques and materials that challenged the definition of painting. His Electric Seascapes combined dots with new, high-tech materials like Rowlux [above], a prismatic plastic sheeting originally developed for reflective highway signs.

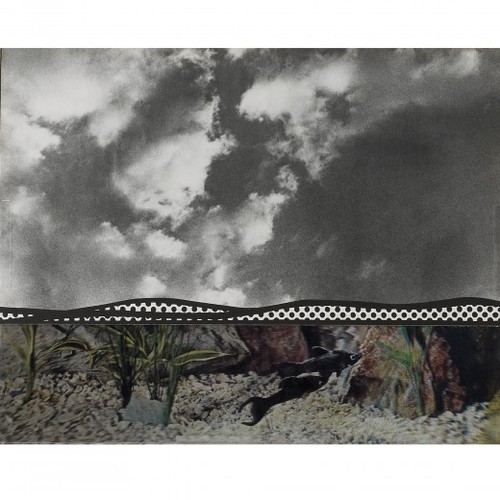

Fish and Sky (from Ten from Leo Castelli), 1967, screenprint, photo and offset, ed. 200, via wright20’s Sept. 15 contemporary sale

When Maurice Tuchman invited Lichtenstein to partner with Universal Studios for LACMA’s ambitious Art & Technology Program in 1968, the artist decided to continue his seascape experiments with motion, perception, and the flat picture plane by creating an actual “moving picture” of a landscape. So yes, this whole thing really fell into place around a seemingly simplistic, even banal play on words.

Sotheby’s pitch boils down the “moving picture” concept as it was exhaustively described in LACMA’s A&T report/catalogue:

[He used] sequences of filmed landscape fragmetns in combination with synthetic images using his trademark Ben Day dot grids or textured aluminum. The project expanded upon ideas he had explored in his landscape collages of 1964 and 1965, which were his most abstract compositions to date. In these works, the constituent elements of landscape were drastically reduced to two or three large areas of Ben Day dots representing sea, land and sky.

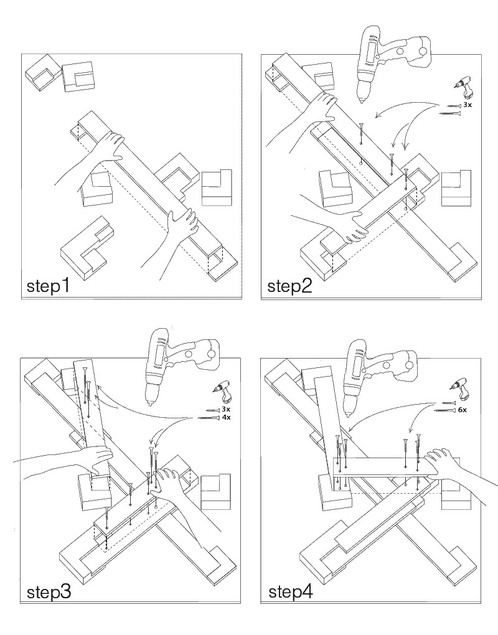

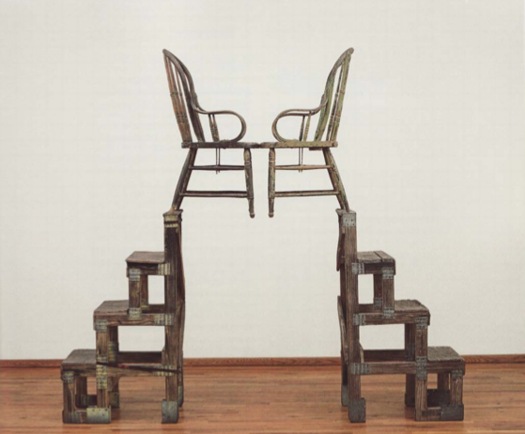

Because of cross-country logistics, Lichtenstein ended up doing almost all actual production with his friend, independent filmmaker Joel Freedman. Roy and Joel spent the summer of 1969 in Southampton, filming the props against the sky or the waves. Assistants would hold the props steady or rock them to simulate the motion of the ocean.

Only it never worked. The movie camera couldn’t accommodate different exposure levels for each component, and the depth of field never resolved to produce the planar flatness Lichtenstein was after. So they threw out the props, shot straight-on shots of the sky and lapping waves, and then added all the graphic elements in post.

I’ll leave the details of the films themselves for a separate post, but the point is, Prop For A Film never ended up in any of the films. And so the exhibition history–both Phillips and Sotheby’s list LACMA and Expo70–is tenuous at best. [Sotheby’s seems to realize this, threading a needle by saying “the work travelled to” Osaka, meaning the film installation. They also get the dates wrong; 1969 was the start of filming. A 2-screen installation at the Expo came first, in 1970, followed by LACMA’s 3-screen version in May 1971.]

Which, whatever, it’s still a large, stunning, early Lichtenstein painting, right? And its provenance, OK Harris–the gallery founded by longtime Castelli director and Lichtenstein discoverer Ivan Karp–is unassailable. Well, it’s certainly a Lichtenstein something.

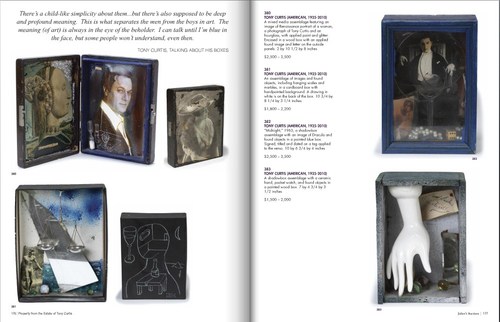

When I first contacted Freedman last year, he told me how he’d saved the piece–it’s Magna on wood, not canvas–after the project ended, and had it on the wall of his loft for several years. The trademark dots meant people would visit and recognize it immediately as a Lichtenstein. Then, when he was in need of completion funds for a documentary–if I remember correctly, it was the mid-70s, so probably Broken Treaty at Battle Mountain–he gave the work to Karp to sell. At Karp’s suggestion, Freedman asked Lichtenstein if he’d help his project by signing the piece, and Lichtenstein generously agreed. The work was sold, and documentary was finished and released to great acclaim.

When he signed it in Karp’s gallery, Lichtenstein also wrote the title on the back. Or maybe it wasn’t a title, so much as a description: Prop For A Film.

Passed at Phillips, Roy Lichtenstein ‘Prop’ Moves to Sotheby’s [observer.com]

Lot 28 Prop for a Film, 1967, est. $400,000-600,000 [sothebys.com]

Lichtenstein’s project writeup from the1971 A&T catalogue [lacma.org]

Previously: Lichtenstein’s Electric Seascapes

BONUS: Freedman is running a Kickstarter campaign to complete a followup film, Land of the Brave. It ends in four days. [kickstarter]