Busy? Oh, yes! But never too busy to turn someone else’s PDF into an artist book!

When @borthwick tweeted this yesterday morning about “a spectacular calibration failure at Google Books” where “Beautiful, digital errors become art,” I knew I’d have to do something.

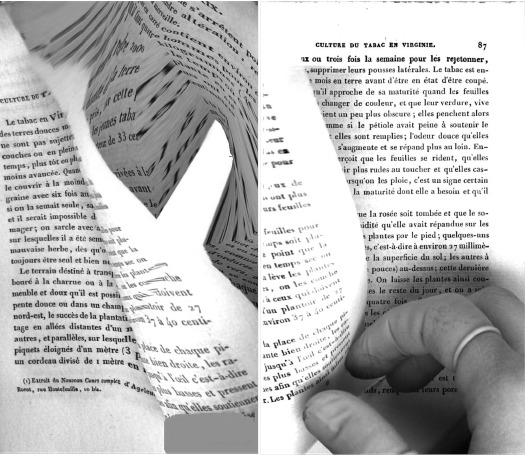

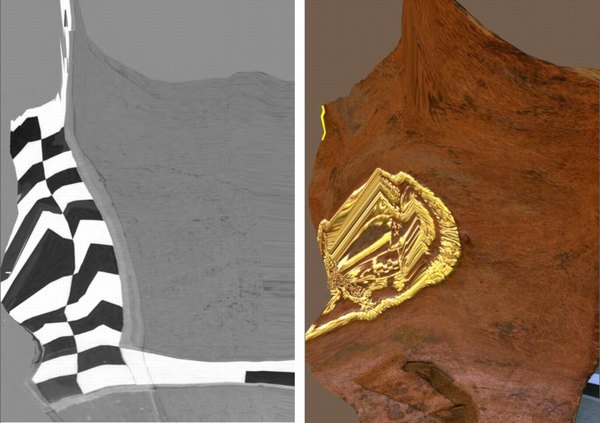

Because as it happens, The Great Picture had me thinking about ways to make a silver gelatin print of the beautiful Google Books scanning distortion I stumbled on last year [above]

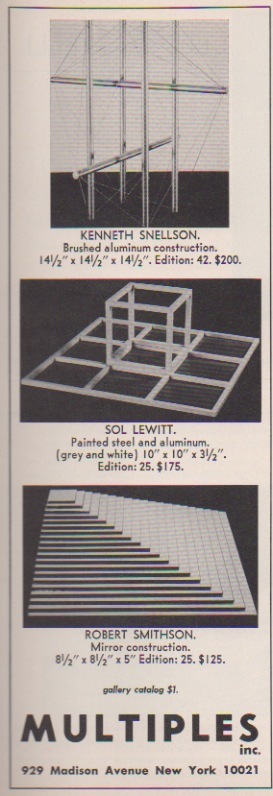

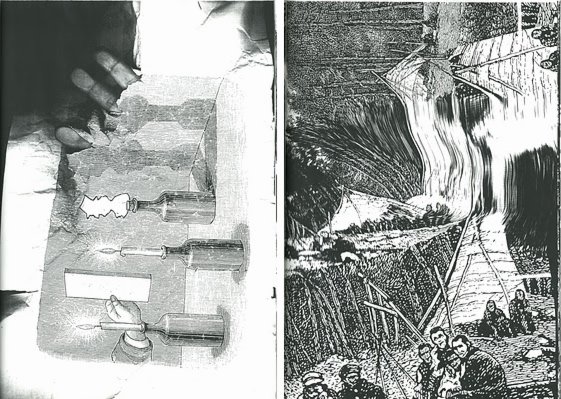

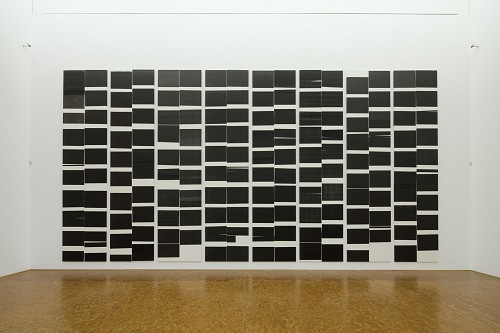

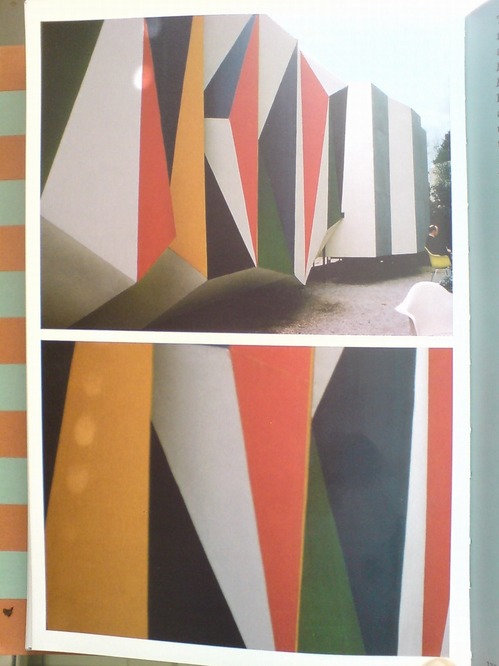

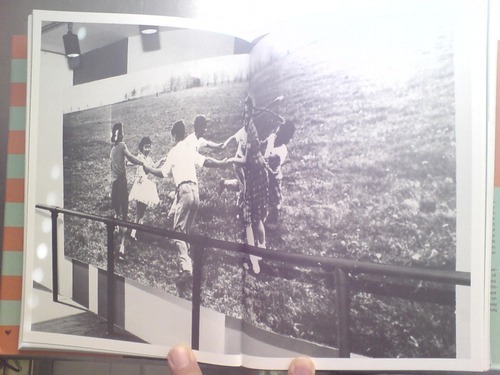

The one that turns out to be similar to–a found, readymade version of–Daphne, Sigmar Polke’s handmade photocopy distortion artist book from 2004.

images from Polke’s Daphne via stopping off place

Then as soon as I clicked through, and saw that it was the whole book, well, my course was set.

According to Google Books, the book was scanned at the Bavarian State Library in Munich on December 15, 2008, a little over a year into their massive digitization initiative.

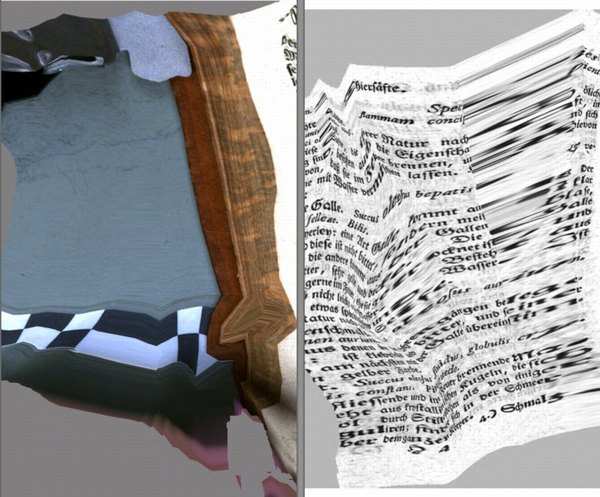

The title of this distorted-beyond-all-recognition-and-come-out-the-other-side-as-art book is is Wohlgemeynte Gedanken über den Dannemarks-Gesundbrunnen, which translates roughly as Well-meaning Thoughts on Denmark’s Mineral Waters.

But [much to Geoffrey Nunberg’s continued consternation, I’m sure] that title turns out to be as glitched up as the pages themselves. According to rare booksellers, Wallerius’s two-part book is actually titled, Hydrologie, oder Wasserreich, von ihm eingetheilet und beschrieben: nebst einer Anleitung zur Anstellung der Wasserproben: wie auch dessen Gedanken vom Dannemarks-Gesundbrunnen,, or Hydrology, or Water Kingdom, divided, and described by him: in addition to a manual for the use of water samples: and also his thoughts on Danish mineral waters..

Hydrologie was originally published in Swedish in 1747, and Wallerius worked closely with Denso on the German translation. But, kind of hilariously, that’s not important now.

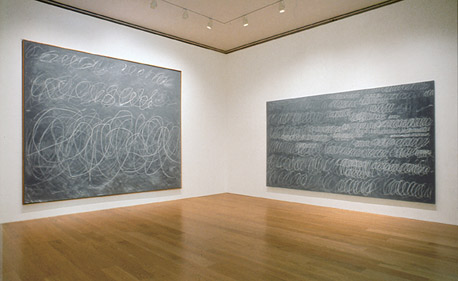

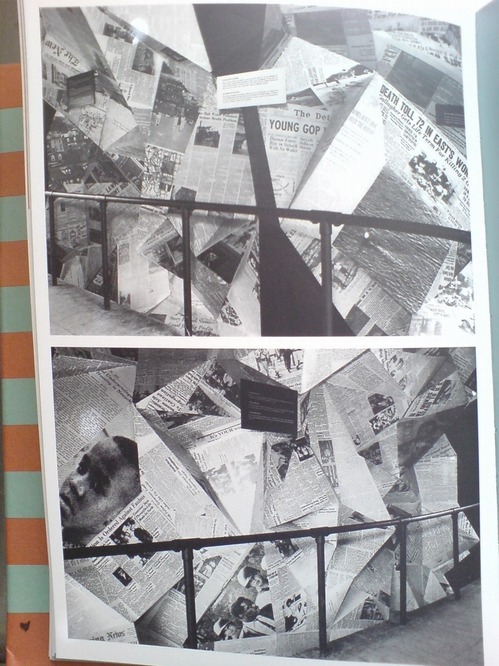

Google Books has remade Hydrologie into something entirely its own, and it’s awesome. Wohlgemeynte Gedanken is a beautiful, revealing mix of inadvertent making-of documentary and algorithmic abstraction. Reiner Speck’s insight on Polke’s photocopied Daphne seem relevant here:

Process is revealed, over and over again. Motifs accumulate page after page, as do small graphic cycles. The printed dot, the resolution, the subject, and the speed all determine and are determined by the apparently unpredictable and often impenetrable secret of a picture whose drafts are akin to the waste products of a copying machine. Even if the motifs in this book provide but a brief insight into the artist’s hitherto secret files and archives, it is still a significant one.

Even more significant when the artist in this case–Google–has also been very reluctant to disclose the secrets and mechanics of its archiving process.

In fact, between the time I started this post last night and this morning, Google Books has removed the distorted copy of Wohlgemeynte Gedanken from its site. In its place now is a plain scan, low-res, but entirely legible, and a digitally generated cover image [but with the same, mangled title]. A side-by-side comparison [above] shows the same underlying scans, which means the distortions–and the fixes–all happened in post.

It also means I’m glad I grabbed the full PDF when I did. And that I formatted it, created a cover, and made it into a print version. Instead of the distorted black and white cover Google Books [still] shows online, I went with a beautiful full-color shot of the gold-stamped leather binding.

Obviously I’m still waiting for the proofs to arrive, so it may change, but right now Wohlgemeynte Gedanken über den Dannemarks-Gesundbrunnen is available as a 283-page, 6×9 paperback facsimile edition. I’m trying black and white first, because an all-color version seemed prohibitively expensive. But then again, what’s the market? Color may yet be the way to go.

The book also includes Google Books’ 2-page boilerplate foreword explaining what they wish would happen with scans of public domain books. Which is adorable.

2015 UPDATE: As the folks who bought the original 2011 edition can attest, the proofs turned out to be slightly underwhelming, losing some of the visual impact of Google Books’ original. But then no one was really buying it that often, so no biggie. But a few weeks ago I went back to see if I could improve the formatting of the book, and now it looks much better. A full-color option may still come, but in the mean time, the 2015 printings are the way to go.

Buy a print gopy of Google Books’ original Wohlgemeynte Gedanken über den Dannemarks-Gesundbrunnen for $16.99 [lulu.com]

Joanne McNeill’s Kantian view of Distorted Scans on Google Books [rhizome.org]

I’m guessing JWZ’s post was the ur-source [jwz.org]

Previously:

distorted diptych from Google Books’ scan of Nouvel Manuel Complet du Fabricant et de l’Amateur de Tabac

Daphne, as photocopied by Sigmar Polke

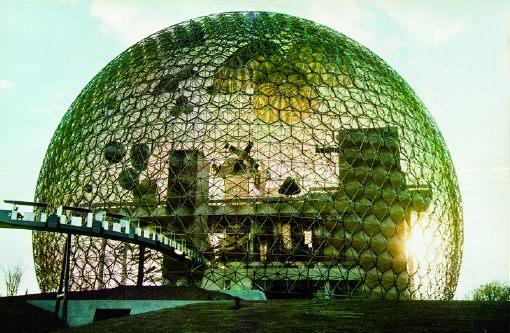

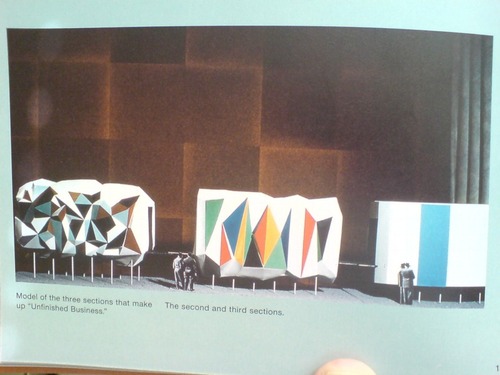

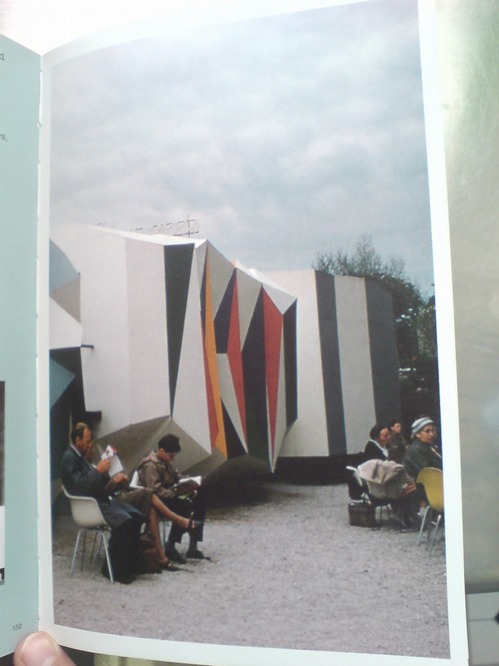

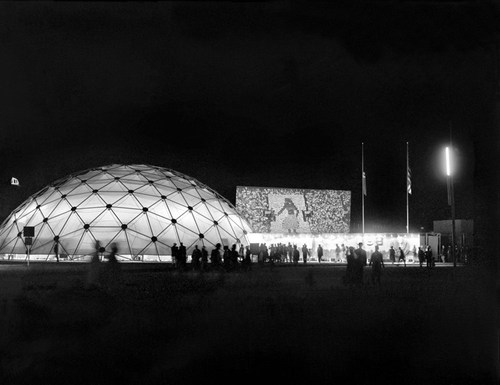

For example, for all the dome- and Expo-loving going on around here, you’d think

For example, for all the dome- and Expo-loving going on around here, you’d think