image: portlandart.net

I confess, I was as taken as the next guy by the Shiny Object-ivity of Jacob Kassay’s electroplated solo debut at Eleven Rivington in 2009. Next guys like Portland Art’s Jeff Jahn, who wrote the show felt “more in touch with the unsettled world of 2009.” And Andrew Russeth, who nailed the charred & mirrored monochromes as “look[ing] like elegantly abused luxury goods.”

And I had a big setup here, which I just deleted, about how I’m really not trying to add to the burgeoning body of Kassay concern trolling, articulated most clearly by Sarah Douglas, about the risks of overnight market success on the emerging artist.

But then I read Ed Schad’s earnest attempt to strip the market hype preconceptions from his review of Kassay’s current show at L&M Gallery in Los Angeles. And I have some issues.

On their face, Kassay and his silvered paintings seem almost too perfectly suited for the Art World’s Next Top Model cautionary tale. It’s like they’re a trap, paintings perfectly calibrated to separate the most narcissistic collectors from their dough. The installation of silvered paintings at Art Basel [below] didn’t help, and neither did Kassay’s dealers’ assertion that the paintings, a suite of eight, would only be sold together–and to a museum–for somewhere around EUR250,000.

It’s hard to counter this narrative; or to wonder how much discourse around Kassay’s work is critical backfilling prompted by dealers or other vested interests. And I think Schad captures the difficulty well, questioning the conceptual underpinnings of Kassay’s show in the face of his monochromes’ unambiguous, materialist beauty:

I get the impression that the center of L&M’s show, a large work on paper placed on rough 2 x 4 studs with a ballet barre positioned in front, is Kassay’s attempt at giving us what may be a position, although that its orientation towards giving the show a conceptual reading also does a disservice. The work is ineffective, pitching a now typical rough D.I.Y look that is often misconstrued for sincerity and humility. Work like this neither sincere nor humble, but instead uses tropes of sincerity and humility as a cop-out for rigorous thinking. I have to admit, that Kassay’s center piece looks grad-school and virtually destroys the mood of refinement and elegance created by the smaller works.

I can’t fault Kassay entirely for this. After all he is young, and perhaps the impulse is to bring a little resolution and a little art history positioning to a practice that is probably more at home in explanation-less experimentation and straight ahead aesthetics. With the ballet barre, suddenly we are allowed to think of performance, of metaphor, of the history of Rauschenberg, his performative collaborations, and his white paintings, the idea of a monochrome as blank surfaces or “landing strips” for dust, light and shadow

Schad’s identification of the monochrome as Kassay’s field of bold engagement is right-on, but I think his skeptical de-emphasis of the artist’s reference to Rauschenberg, the conceptual and the collaborative is a mistake. These may turn out to be central elements of Kassay’s practice.

From the L&M press release:

This installation conceit engages Kassay’s interest in artist collaborations such as Rauschenberg and Johns designing sets for Merce Cunningham performances and an abundant history of multi-media collaborations. It evokes these ideas, but also takes into consideration the gallery as a place for practice, repetition and the natural gradients provided by the light, the white walls and the work itself.

Which, hmm. There’s a crossed up analogy there–sets and performance vs barre and practice–which effectively conflates gallery show with studio practice [all puns presumably intended].

I didn’t want to be all Johnny one-note, but since he/they mentioned him first, I can now point out that the paradigm Kassay’s debut on the art world stage most closely resembles is not Ryman or Klein, or even Rauschenberg, but Johns. Rauschenberg’s 1953 Stable Gallery show of white and black monochromes was more scandale than succes, and he fought the unserious bad boy image for many years, while Johns’ work was hailed–and sold–right out of the gate. And while flags and targets might stand out, most of Johns’ earliest exhibited works [1957-58] were monochrome paintings.

And though Rauschenberg’s reputation as a dance collaborator is well known, somehow Johns’ image of painterly solitude persists [at least for me], even though he was deep in the mix. Here’s a quietly remarkable comment Johns made in 1999, while discussing the creation of the artists-for-artists-oriented Foundation for Contemporary Arts, which he still heads:

In 1954 I had helped Bob Rauschenberg a bit with his Minutiae set, his first for Merce Cunningham, and I continued to assist him with most of his stage work through 1960. We were friends with Merce and John Cage and saw them frequently. In 1955 there was an evening of Cunningham/Cage performances at Clarkstown High School in Rockland County where we met Emile de Antonio. In 1958 de, as he was known, Bob and I formed Impresarios Inc. which financed and produced the 25-year retrospective concert of John Cage’s music at Town Hall in New York.

I guess this is all an aside, but the Walker is preparing Dance Works I: Merce Cunningham and Robert Rauschenberg, a show this fall of their Cunningham archive holdings which, at least in the title, doesn’t consider Johns’ collaborative role. Not that the Walker ignores Johns’ dance work; they have his Duchampian set structures for Walkaroundtime, after all.

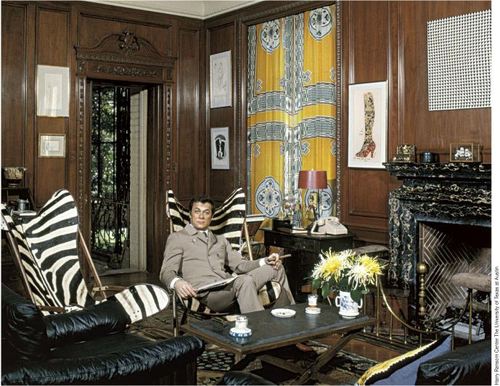

henry codax, installation view, via carriage trade

So what’s this got to do with Kassay? Are his only collaboration references in his L&M show? In fact, he’s apparently got another show up right now which takes the model collaboration and the issue of individual artistic creation and authorship head-on. Andrew Russeth reports that Carriage Trade’s current show, an exhibition of monochrome paintings by the fictitious artist Henry Codax, is actually a joint project of Kassay and the minimalism-inflected French Swiss conceptual artist Olivier Mosset.

And now that you mention it, in May 2010, before any of the auction madness, Kassay opened his show in Paris with a collaboration as well. Iconic minimalist trumpter/composer Rhys Chatham performed at Art Concept, with a pair of Kassay’s silvered paintings as a backdrop. Watching video of the gig [Here are parts 2 and 3, total runtime is about 55 minutes.], I’m struck by how the paintings function as screens, reflecting the movements of the small, otherwise invisible crowd.

For the two previous summers, at least, the Paris-based Chatham loomed large in New York. His landmark composition, A Crimson Grail, an orchestra for 200 electric guitars, was rehearsed and rained out at the last minute in 2008 as part of Lincoln Center’s Out of Doors series. It was finally, triumphantly performed the next year. Andrew Hultkrans recounted the euphoric experience for Artforum.

In September, Primary Information is releasing a limited edition LP of the Kassay performance, with an additional work, under the title, Rêve Parisien. And in October, Kassay is having a show at the ICA in London, which is apparently still operating. For the moment, Eleven Rivington is surprisingly not mentioned in ICA’s brief bio of Kassay.

UPDATE Ultimately I’m glad I ended so abruptly; maybe it was enough to spur Andrew into action. He reminded me of the collaboration I’d forgotten, the one which had finally pushed me over the colabo-writing edge. From Karen Rosenberg’s NYT review of this year’s so-called Bridgehampton Biennial, where the backyard is strewn with Lisa Beck’s satelloon-lookin’ sculptures, and the front yard features a 1964 Ford Galaxy awaiting “an ‘artist’s renovation’ by Servane Mary, Jacob Kassay and Olivier Mosset.” Those shiny silver balls’ll throw me ever’ time. [Of course, this show also brings up Bob Nickas’s role in launching Kassay’s work into the discourse. This is at least the third Nickas-curated show to include Kassay. Dance with the one who brung ya.]

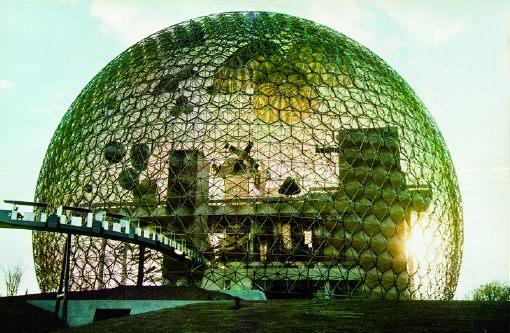

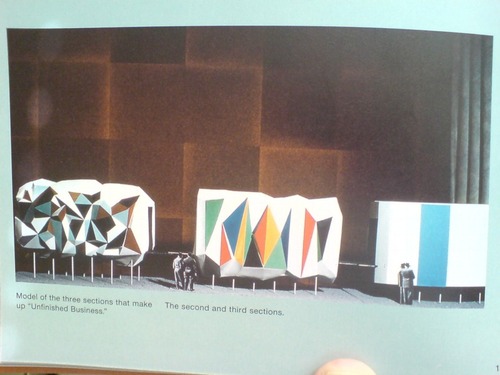

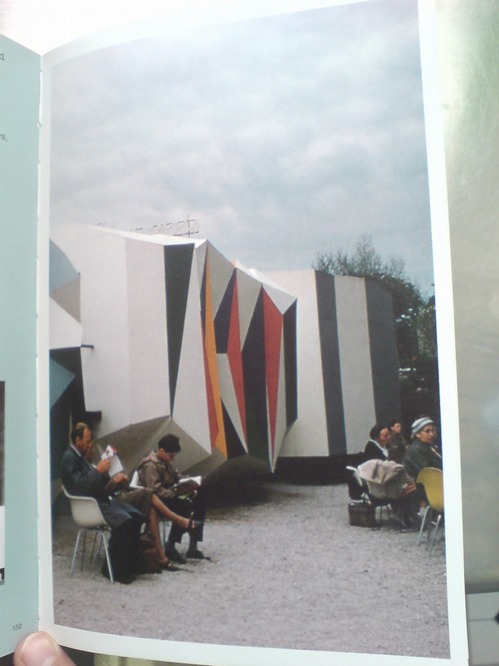

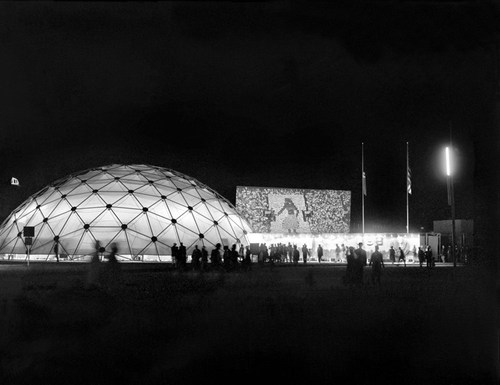

For example, for all the dome- and Expo-loving going on around here, you’d think

For example, for all the dome- and Expo-loving going on around here, you’d think