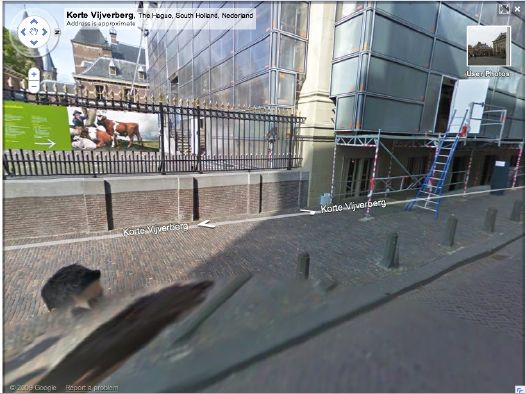

Because I now appear to be constitutionally incapable of doing otherwise, after mentioning the Mauritshuis, the Vermeer-loaded Royal Picture Gallery in The Hague, I checked to see if was camo-obscured on Google Maps.

[I kind of knew it wasn’t, because it’s situated smack in between two prime Dutch Camo Landscapes: the Noordeindepaleis and the Ministry of Defense HQ, but I looked anyway.]

And while we knew that Google Street View has come to Den Haag, I didn’t realize it was just a couple of months ago. And with the Google Trike, no less.

Here’s where the museum–a 17th century mansion, is supposed to be, but whoa.

It’s apparently camouflaged as a generic glass & steel office building. Took me three passes to find it. By which point, I became kind of fascinated with the way Street View knits together its panoptic images, particularly when they include people. I love Google’s Cubist-meets-Robert Lazzarini-meets-Julia Scher-meets Hans Holbein the Younger portrait style.

What I Looked At In 1995: Vermeer’s View Of Delft

The inconvenient intrusion of war and political upheaval [i.e., the collapse of the Dutch government and the looming withdrawal of Dutch troops from their frontline deployment in Afghanistan] into my Dutch Landscapes project has sent me trying to re-find some discussion of Vermeer that’s stuck with me for years.

Like so many hundreds of thousands of others, I made a trip to the National Gallery in Washington in the winter of 1995 to see the first Vermeer exhibition in almost 300 years. It was a DC that may be hard for folks today to even conceive of: the show was abruptly opening and closing, thanks to massive snowfall and two government shutdowns orchestrated by an obstructionist Republican agenda led by Newt Gingrich. [I know, right? He seems so nice.]

Anyway, 21 of the world’s 35 Vermeers were there, including View of Delft, loaned by the exhibitions only other venue, the Royal Gallery at the Mauritshuis in The Hague.

The Essential Vermeer puts the date depicted in the painting as early May, 1660 [the evidence: leaves on the trees, the boat activity, and the empty tower on the Nieuwe Kerk, because the bells were in the shop]. It seems so banal, so placid, so idyllic.

But I remember reading a discussion of how deceptive, or at least complicated, this peace was, in light of Delft’s own history. The argument centered on the high-contrast beam of sunlight Vermeer punched through his rainclouds to illuminate the Nieuwe Kerk, in the center background of the painting.

William of Orange had used Delft as a base for launching in 1568 what became the Eighty Years War, against Spain, the Hapsburgs, and the Holy Roman Empire, which turned on issues of religious intolerance, taxation without representation, and centralized power. William was assassinated in 1584, and because his family’s traditional seat, Breda, was still in Spanish hands, he was interred in the Nieuwe Kerk. So are his successors in the House of Orange-Nassau, who continued the fight, and who have ruled the Dutch Republic since it won its independence with the Treaty of Westphalia, which was signed on May 15, 1648.

But wait, there’s more! In 1660 the city was also still recovering and rebuilding after the Delft Thunderclap of 1654, a massive gunpowder explosion at a waterfront munitions warehouse that killed over 100 people–including one of Delft’s most well-known painters, Fabritius Carels–injured thousands more, and leveled a huge section of the city.

If Vermeer were alive in 2013, then, the equivalent painting might be the rainy skyline of lower New Amsterdam from the Hudson, where a ray of sunlight picks out the details of an unobstructed St Paul’s church–if George Washington and all the subsequent presidents were buried there. If there’s a Dutch equivalent of a bald eagle with a tear in its eye, Vermeer showed remarkable restraint by not including it.

UPDATE I’ll get out my DVD set in the morning to confirm, but I think Tyler Green’s right, it’s the first essay in Lawrence Weschler’s 2004 book, Vermeer in Bosnia, which was originally published as “Inventing Peace,” in The New Yorker, Nov. 20, 1995.

Yep, here we go, Weschler’s setup for the remarkable story of how the head of the International War Crimes Tribunal in The Hague kept himself sane by looking at the Vermeers at the Mauritshuis:

For, of course, when Vermeer was painting those images, which for us have become the very emblem of peacefulness and serenity, all Europe was Bosnia (or had only just been): awash in incredibly vicious wars of religious persecution and proto-nationalist formation.

Wow, maybe I should re-read the whole thing rather than post updates every page, but. Weschler quotes Harry Berger’s idea about Vermeer’s deployment of “‘conspicuous exclusion,’ of themes that are saturatingly present but only as a felt absence.”

What a fantastic phrase, which immediately reminds me of a comment left by Jerome Bertrand on Ogle Earth’s original 2006 coverage of the Dutch Google Map censorship issue:

All the same, someone at Royalty level (AIVD?) would choose to typically blur out certain private residences – so it ends up you can find them quicker than others by just scanning for blurred spots in the area. This is helpfull [sp] when you need to know what’s hot.

Echo Echo

The giant, reflective aluminized mylar satelloons of Project Echo were designed to be seen by the naked eye from anywhere on earth. As I trace down depictions and accounts of seeing them, I wonder how watched they actually were outside the scientific community.

Echo II was launched January 25, 1964. Shortly afterward, scientists at Sandia Corporation calculated the crossing of the two satelloons and snapped this photo, a 6-minute exposure. Echo I [100-ft diameter, 870-mi. orbit] is traveling from the upper left. Echo II [135-ft dia., 670-mi. orbit] is traveling from the lower left. The photo was a double page spread in LIFE Magazine on Feb. 28.

Sandia was a division of Western Electric, a subsidiary of AT&T, which ran the Sandia National Labs in New Mexico. It was a different division from Bell Labs, the division of AT&T which ran the Echo communications system on the ground. Sandia is now owned by Lockheed Martin, which manages it for the Department of Energy.

I think I’d now like to track down some vintage prints of this photograph, and not just the copies of LIFE, which I already hoovered up from eBay.

“Heavy Traffic In Outer Space,” Feb. 28, 1964 [LIFE via Google Books]

Related, but the exact opposite: Trevor Paglen’s The Other Night Sky

Dutch Camo Landscapes On Google Streetview? Nee

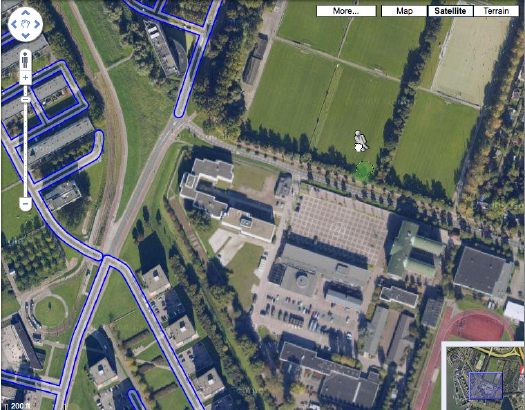

You may recall how Google Maps recently changed the polygonal camouflage on one of the Dutch landscapes I was using for my painting project.

I was back there, getting a clean shot of the nicely distorted grid plaza–the site belongs to the Koniklijke Marine, the Royal Navy, and is apparently the home address for the Royal Marine Band–when I saw that the Streetview icon was activated. Looks like Google’s camera cars reached the football field-filled outskirts of Rotterdam.

But not all of them. The available imagery shows that Google is excluding all street-level imagery from around the camo’d compound. The previous official explanation for camo-obscuring intelligence-sensitive sites was that the Dutch government claimed jurisdiction to censor aerial photography, but not satellite imagery. I guess there’s another law that forbids street-level photography from public roads, too? Yes and no.

A quick stop at the ur-Dutch Camo Landscape, the Noordeinde Paleis in The Hague, shows that Streetview is unavailable for its entire perimeter. But the other camo’d complex, a Royal Garage or something, to the northwest through the park, shows up just fine. The south perimeter of that giant, cut-n-past camo blob is just fine, which makes me think that the building being camo’d–I think it’s the HQ of the Defense Ministry itself–is on the next street up, which is, indeed, blocked. Unfortunately, Noordwijk ann Zee, the beachfront town that is the site of my favorite inexplicable, airdropped camo blob, has not yet been added to Streetview.

Update: In actual governmental/military news, the Dutch coalition government just collapsed in the face of growing opposition to extending the deployment of 2,000 Dutch troops in NATO’s operations in southern Afghanistan.

On Reading Auras

As you can guess from the mentions of Sherrie Levine, I’ve been studying the issues around copying and reproducing and originality and authorship. And whenever you do that, Walter Benjamin comes up, specifically his concept of aura.

Basically, it’s what an original work of art has that a reproduction doesn’t. Except when it does. It’s what declines or disappears in the process of mechanical reproduction–especially in the cinematic process, which interested Benjamin greatly–but then it comes back sometimes. Somehow.

Just in case quoting or arguing Benjamin at length is tedious or pretentious to the Twitterized reader, I’m putting a few quotes and sources after the jump, for my own reference later. They are:

Sherrie Levine

John Perrault

Samuel Weber

Grant Wythoff

Miriam Brantu Hansen

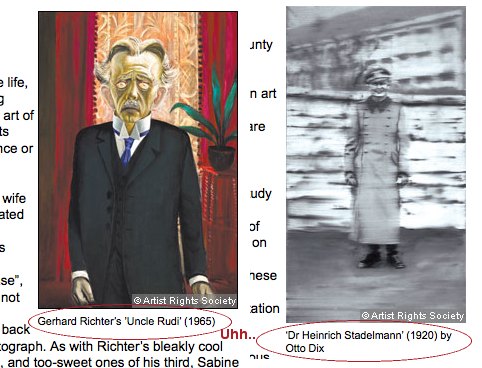

Uncle Rudi, Is That You?

Who are the freaks and nerds who call out picayune corrections in newspaper articles? Me, for one.

On a New York Times piece I did once, I changed an entire line during the copyediting process. The piece was much, much better for it, I think, but I got chewed out afterward because, apparently, it required several people staying late to re-layout a whole page, which delayed the closing of the section.

As penance, I’ve been pretty fastidious ever since about quickly slipping the Times’ web editors little corrections–usually of peoples’ names, ex the kind of things that might cause unnecessary embarrassment–for Arts stories. [Oy, in one pseudo-liveblog post from Miami Art Basel, the correspondent misspelled basically every name she dropped. And no, it was not Linda Yablonsky; she is an exquisite name dropper.]

Anyway, last weekend, the Financial Times mentioned the new Gerhard Richter biography in Jackie Wullschlager’s survey of books on German painting. Their whole point was about how loaded Richter’s blurred portraits of his family were, such as Uncle Rudi.

The FT transposed the captions with the Richter and a portrait by Otto Dix. When I tried to do my typical one-click correction, I was surprised to find that the FT doesn’t appear to even publish an address for corrections. Or for reaching the editors.

Setting aside the whole implication that the very idea of being corrected didn’t cross their minds, the whole FT website contact interface turns out to be oriented to subscribers/users and the support of the paid consumption experience.

As such, it has taken a week for me to receive an automated reply, and now my comment had been forwarded to the appropriate department. As the fresh screenshots show, the error remains.

Gareth Long’s Untitled (Stories)

Gareth Long’s giant lenticular prints based on the iconic-yet-anachronous 1991 cover designs for JD Salinger’s books are freaking me out right now.

They’re like Noland or Morris Louis canvases, reanimated through some immediately dated, retrofuturistic technology. Something an aesthete in an early Star Trek movie might have had hanging on his wall. Jeremy Blakes that still work in a blackout.

Which is why they freak me out so much. A Color Field painting hangs unobtrusively, even decoratively, on the wall. A Blake requires turning it on and watching it. You can’t work with those things on in the background, any more than you could sleep with the Flavin on.

Long’s lenticulars thwart all that passive/active viewing negotiation by always being on. If they’re in the room with you, you can’t not look at them.

Go ahead, try it. They’re on view through next weekend at Kate Werble Gallery on Vandam St.

Above: Untitled (Seymour) is the most Salinger cover-esque, while Untitled (Zooey) is the most unabashedly psychedelic. Both images are from Long’s site, where he also offers video clips of the pieces.

Colby Chamberlain ties this “restless” aspect to Salinger in his Artforum review [artforum]

Untitled (Stories) [garethlong.net]

On Printing German Wallpaper & Richter’s Film

For their “Art of Two Germanys” show in 2008, LACMA recreated part of a 1966 gallery installation by Gerhard Richter called Volker Bradke, which was designed to mimic or reference the postwar German bourgeoisie’s penchant for ticky tacky floral wallpaper.

But instead of real wallpaper, the museum used an artifact from the original installation, loaned by the piece’s owner via the gallery: a rubber stamp roll with a design carved into it. LACMA’s curator and gallery manager talk here about printing up the walls, but for some reason, I just can’t get enough of this video of them actually doing it.

This reminds me a bit of Christopher Wool, and it’s a fantastic-looking method of generating an image. Or a design, or a surface, whatever you end up calling it. The fact that it’s a painted simulacrum and not actual wallpaper, though, seems pretty relevant, as does the curator’s instruction that “the printing is not supposed to look perfect.” It sounds like an early example of Richter reminding the viewer that he’s looking at an image, not the thing itself.

Anyway, this is all coming down today because Bradke is the subject of Richter’s only film, a 14-min black & white short which was part of the installation. It’s just been released on DVD, along with a book, »Volker Bradke« und das Prinzip der Unschärfe [“Volker Bradke and the Uncertainty Principle] by art historian Hubertus Butin. From what I can tell, the whole project was designed to turn Richter’s friend and studio assistant into a celebrity, using paintings, posters, banners, and a fawning profile film. We’ll see how the film turns out when it arrives; but so far, Richter doesn’t seem too compelled to revisit the medium. [via @gerhardrichter]

Wallpaper in Art of Two Germanys, part II [lacma blog]

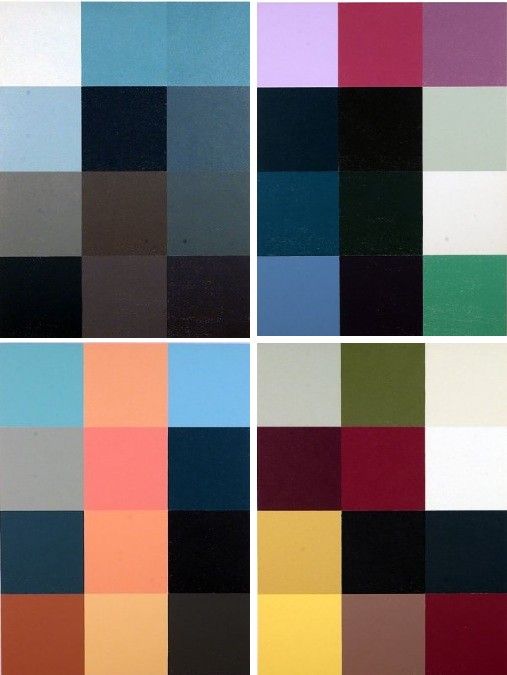

More Levine, More Meltdown

Here’s Sherrie Levine talking in 1993 about the making of her Meltdown woodblock print series with BAM’s Constance Lewallen in the Journal of Contemporary Art. Levine did just what Susan Tallman, who reviewed Meltdown kind of negatively in 1990, feared: she used the computer algorithm to color-average the entire images of Mondrian, Monet, etc., and then she used the “Mardenesque” greys to paint monochrome canvases. It wasn’t a bug, it’s a feature.

The JCA transcript has a funny find&replace quirk, where all the SL’s were replaced with Levine [e.g., slide >> Levineide]:

Lewallen: You did some woodblock prints recently, I noticed, that had to do with the “Meltdown” paintings. Where did you do them?

Levine: I worked with a wonderful printer, Maurice Sanchez. I had wanted to do prints based on a geometric grid with computer averages of colors of modern master paintings.

Lewallen: Which paintings did you use as a starting point?

Levine: For example, we used a Monet “Cathedral.” We put a Levineide of the picture into a computer with graphic capabilities and the computer created a grid in which each section corresponded to an average of the color in that section of the painting. The “Meltdown” paintings are based on the same principle but rather than being gridded off, they represent one uniform average for the whole surface. In fact, it’s funny, I had been wanting to make work after Marden’s early work, because some of his monochromes are some of my favorite paintings. For me they are the ultimate late-Modern paintings. I am also a big fan of Olivier Mosset’s monochrome paintings, and Yves Klein is another favorite of mine. For years I have been trying to think of a way to make monochromes that were interesting but not the same as those I admired, but I never came up with a solution. Then, when I was working on the print project, almost as a mistake, the computer also gave me the color average of the entire . . .

Lewallen: So, the print project preceded the paintings?

Levine: Yes, the average of the entire painting, all the colors in the painting, like when you mix your whole palette together you get these beautiful, Mardenesque greys and greens and mauves. And I realized I had finally found a method.

Lewallen: What were the colors like in the prints, working with color mixes from grid to grid?

Levine: They were much less greyed down than the paintings.

Lewallen: Depending on the section.

Levine: I originally thought they should be lithographs or silkscreens, and Maurice came up with the wonderful idea of woodcuts on Japanese rice paper. He used a high-tech method; he made a grid of the twelve tongue-and-groove blocks using a laser saw that he inked up separately and printed all at once. I liked the combination of high-tech and low-tech techniques.

Levine’s Meltdown (After Yves Klein), 1991, was in Daniel Birnbaum’s Italian Pavilion at Venice last year. AFC got the photo, if not the concept.

What I Looked At Today: Sherrie Levine’s Meltdown

Reductivist abstraction and pixelated photo-appropriation? If only it could involve a short film, an Ikea table, or a White House stage set, I could wrap this whole blog up with a bow and go home.

From Peter Blum Editions’ text accompanying Sherrie Levine’s 1989 print series, Meltdown:

The twelve-color woodblock prints in the portfolio Meltdown have been created by Sherrie Levine by entering images, after Duchamp, Monet, Kirchner, and Mondrian into a computer scanner that spatially quantizes and transforms these images into the minimum number of pixels, thus determining each of the colors in the four prints.

after Duchamp et al, means these are pixelated prints based on Levine’s own photographic reproductions of photoreproductions of [clockwise from upper left], a Monet’s Rouen Cathedral, Kirchner’s Potsdamer Platz, Berlin, Mondrian’s Composition No. II, and Duchamp’s L.H.O.O.Q..

I’d started tracking down links to the “original” works, Levine’s source paintings, before realizing that kind of missed the point. In fact, as with her earlier rephotographic series, Levine’s source images are reproductions in books. In 1987 she showed 40 photos, all 1982, of reproductions of works by Monet, Kirchner, and Mondrian at the Wadsworth Athenaeum. [pdf of the exhibition brochure].

For one contemporary reviewer, Levine’s use of a computer, her deployment of algorithmic color averaging, and the whole “pixel” concept gave Meltdown the whiff of suspicious techno-novelty. I obviously think it’s a fresh and worthy approach, which now makes me wonder a bit. I’m also kind of fascinated by her use of woodblock, which was either a 4- or 12-color process. Either way, it seems an important, digital-to-analog color translation step is being largely ignored.

What’s also remarkable is that Phillips ran the After Mondrian image on the cover of the catalogue for it editions auction last fall, even though the suite for sale was an unsigned, undeclared set outside the edition [35 + 10AP], which was marked simply “WKSHP 1/2.” It still sold for $12,500.

Levine made at least one other pixelated print series. Equivalents: After Stieglitz 1- 18 are greyscale inkjet prints from 2006, and were shown at the last Whitney Biennial.

That Minnesota Skyway For Sale Again/Still

In this difficult real estate environment, close followers of the used modernist Skyway market will note have reason to be optimistic. Even as asking prices have dropped nearly 40% in the last year,–from $79,500,to around $49,500–they are still way above 2002 and 2006 results of $1 and “a very small amount” that’s probably closer to $1 than $49,500, respectively.

SKYWAY FOR SALE – AGAIN!!! [minneapolis.craigslist.org, thanks sheree from aol]

City Desk Studio architects for all your used Skyway needs [citydeskstudio.com]

ZERO Adds A Zero

Wow, Sotheby’s auction of iconic Zero works from the Anne and Gerhard Lenz collection today in London went through the roof.

Whether it was the recent renewed critical interest in key Zero artists beyond the big names–from Klein, Fontana and Manzoni to Otto Piene, Gunther Uecker, Jan Schoonhoven–or just shrewdly low estimates on fantastic works, the sale was pretty impressive.

There’ll be no more haggling over stray assemblages in the empty aisles of Art Rotterdam after this, I tell ya.

top: Lot 2: Rauchbild, 1961, Otto Piene, est 35-40,000 GBP, sold 223,250 GBP.

above: Lot 3: HAAR DER NYMPHEN, 1964, Gunther Uecker, est. 100-150,000 GBP, sold 825,250 GBP

ZERO art from the Sammlung Lenz Schoenberg, Feb 10, 2010 [sothebys]

Previously: Otto Piene on The Mall – Centerbeam and Icarus

100 Colours Down, 4800 To Go

The Collection Of Duda Miranda

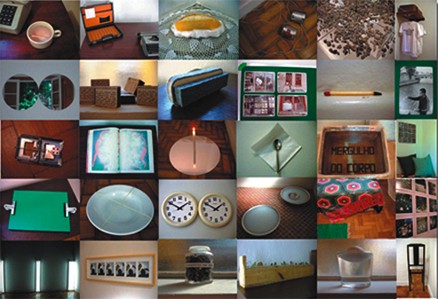

So from what I can gather, Duda Miranda is a fictional collector persona, created by an artist, who collects by fabricating replicas of conceptual artworks. He first exhibited his collection in his [or someone’s] house in Campinas, Brazil, in 2003. But apparently, he kept on making/collecting, and in 2007, the Museu Mineiro in Belo Horizonte, exhibited the collection and published a catalog, which was distributed to “schools and art institutions.”

Included in the collection are replicas of works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres, Cildo Mireiles, Helio Oiticica, Joseph Beuys, Rivane Neuenschwander, Sophie Calle, and Sol Lewitt. From the thumbnails above, it looks like there are early Dan Flavins and Olafur Eliassons as well. A condensed auto-translation of Duda’s 2003 statement:

My collection is simple: do not buy artwork, redo them. For me art is mental and in some way, every time I encounter a job and I am affected by it, I have it or am possessed. So I am led to believe that art is both the artist and mine, she is in the world. And it learned from the art itself, it is learning, learning is built.

My collection is composed primarily of learning. Nothing to do with books. Forget this is perhaps the first step (Beuys: Noiseless Eraser). Collection Duda Miranda is like a series of propositions, each working a proposition. My choice is guided by the method invented to collect, certain jobs require living, give me. Do not build up, a repeat experiment.

The collection that bears my name will be considered false by many – most experts. I learned the power of art is to affect and be affected, the rest is shadow of alien powers.

I first learned of Miranda’s collection project in Irene Small’s Artforum article about the fire that damaged and destroyed many pieces of work by the late Brazilian artist Helio Oiticica. According to Small, Miranda’s “deterritorialization” was a “paradoxical reminder that the afterlives of works of art inhere not in singular possession, but in collective use.”

Also, in exploring the ramifications of the fire for Oiticica’s work and influence, just at a time when his global prominence as a pioneer in so many fields of postwar art practice has been rising, she cites unnamed Brazilian “commentators” who

argued that Oiticica’s works had become fetishized, some going so far as to say that the fire had “liberated” the artist’s ideas from their material cage. Oiticica’s works, according to this reading, are primarily prompts for experience and better conveyed by propositions and writings than by physical remains. Of course, this idealist position also has its market version, as propositions and projects are easily editioned and sold when remade.

It’s remarkable that it’s remarkable that this antipathy toward the “fetishized” or commodified art object has such currency in the Brazilian context, whether in the debate over Oiticica’s fate or official sponsorship and promulgation of Miranda’s self-concious counterfeiting.

For all the griping and, the US/Europe art world still feels like it exists within the market paradigm. And it’s a paradigm which subsumes even the essentialist ideas behind much of the art of the last fifty years. So it’s kind of fascinating to see art in an alternative reality where the concept takes precedence over the certificate.

All that said, I can’t find the supposed online catalogue anywhere, nor can I find anyplace to see or buy the print version. Portuguese readers, help an irmão out?

update: According to this PDF text from her site Marilá Dardot cooked up the Duda thing with fellow artist Matheus Rocha. Thanks to Joao for the info.

What I Looked At In 2000: Torben Giehler

As soon as I started thinking that Dutch Polygonal Camo on Google Maps would make great abstract landscape paintings, I thought of a some giant, abstract, polygonal landscape paintings I’d seen way back in 2000-2. But for the life of me, I couldn’t remember the artist’s name. From Julie Mehretu to Edvard Haberkost, to Benjamin Edwards to Kevin Appel to Carla Klein to Jules de Balincourt to Thomas Scheibitz, large-scale, geometrical/architectural/spatial/digital/landscape abstraction has not been in short supply. And of course, it was none of the above.

I’d seen one at “Collector’s Choice,” the exhibition I co-curated at Exit Art in the winter of 2000-1. It was on Norman Dubrow’s crazy, salon-style wall. Then the one that really haunted me was in a 2001 show at Caren Golden Gallery, curated, I think, by David Hunt. And then there was another show somewhere later, a solo show.

Well, thanks to, of all people, Mark Kostabi, I just realized it was NY/Berlin painter Torben Giehler. And the gallery was Leo Koenig, in 2002.

In her 2002 review of Giehler’s Koenig show, Roberta Smith described the artist as one of several interested in “formalist abstraction, digital cartography and photography.” She also guessed that making the paintings “must require hours of applying masking tape.” And sure enough, the many studio photos on Giehler’s website show piles of balled up blue tape, and also small printouts taped next to the canvas. It looks like he begins his work on a computer, and then enlarges and transposes the compositions by hand. [This 2004 Art in America review is excellent for describing the painting’s production, while adding absolutely nothing to their context or understanding.]

Some of Giehler’s landscapes are gridded; the earliest painting on his site is an explicit Mondrian flyover, a psychdelic reworking called Boogie Woogie. But his polygonal landscapes seem to form structures of their own. Like the mountain series he showed at Koenig. K2 is a favorite. [And a favorite of Giehler’s, too, apparently; he made a series of prints of it with Fawbush.] And Matterhorn has a very Dutch color scheme.

Glad to clear all that up.

above: Tomorrow World, 2001, by Torben Giehler, exhibited in “Superimposition,” Caren Golden Gallery [torbengiehler.com]

Torben Giehler’s website [torbengiehler.com]