Paddy and her commenters have already done a pretty good job sorting through the decision in the Cariou vs. Prince & Gagosian case, and there are other folks out there with far more expertise and time than I who are also weighing in.

And while I still think this case is really troublesome for the whole fair use ecosystem as it applies to the art world–or more specifically, to artistic practice–that effect may not be lasting or widespread. Fair use and transformative work are still messy, ambiguous principles, almost by design, and artists are gonna do what artists have to do. And really, Judge Batts’ decision is so poorly constructed, and ignores or misconstrues so many basic facts of the case, that it can’t hold up to the inevitable, coming scrutiny, much less serve as any kind of practical impact going forward.

Still, it’s so awful, I can’t let it go without calling out a few of the most egregious passages, arguments, and errors. So here goes.

1) Cariou’s Photos Are Copyrighted. NO $#%ing DUH.

This is the first section of Judge Batts’ decision, and it has gotten a lot of media mention from the skimming crowd, even though it seems utterly and entirely irrelevant to anything at all. [p.10]:

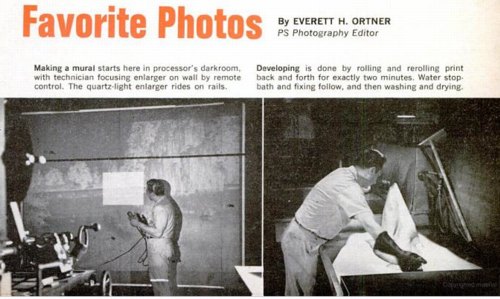

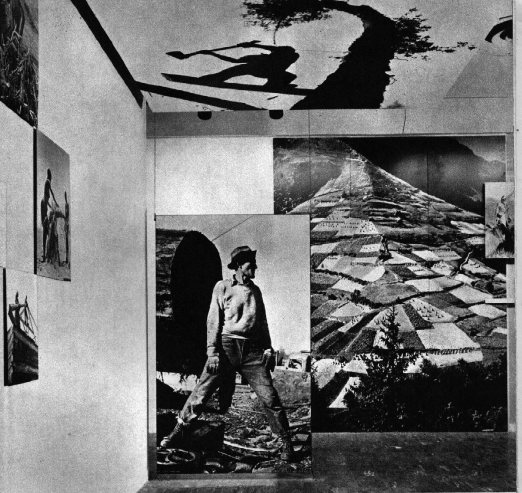

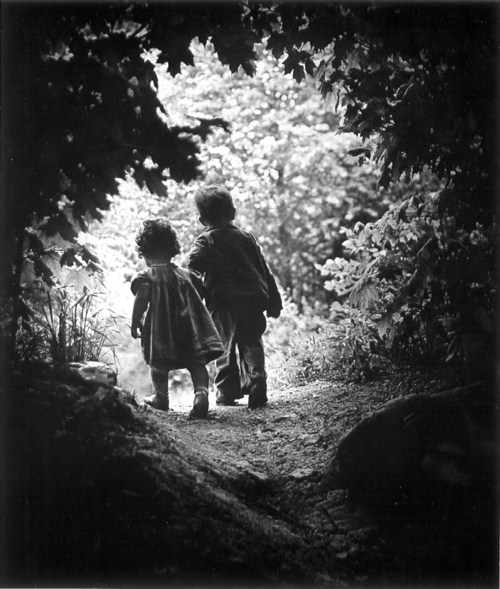

Cariou’s ownership of a valid copyright in the Photos is undisputed. However, Defendants assert that Cariou’s Photos are mere compilations of facts concerning Rastafarians and the Jamaican landscape, arranged with minimum creativity in a manner typical of their genre, and that the Photos are therefore not protectable as a matter of law, despite Plaintiff’s extensive testimony about the creative choices he made in taking, processing, developing, and selecting them.

Unfortunately for Defendants, it has been a matter of settled law for well over one hundred years that creative photographs are worthy of copyright protection, even when they depict real people and natural environments.

I have looked, and I cannot find any documents where Defendants actually made this ridiculous claim that Cariou’s photos–arty, black & white, published in a book–are not copyrightable. It’s like the stupidest tumblr excuse ever [I found this image on the Internet, so it must be public domain!], not the argument the copyright lawyer for the most powerful art dealer in the world would make. Why is this even in here?

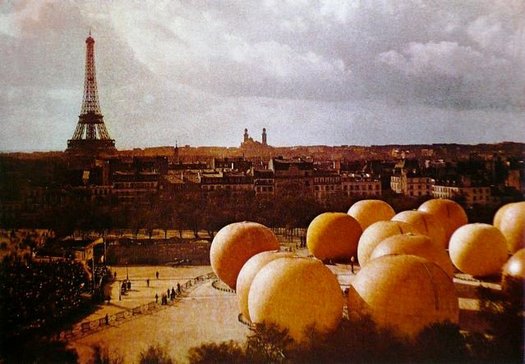

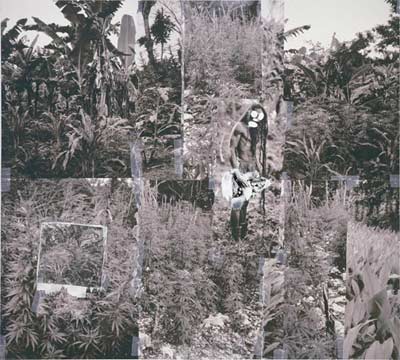

Look, the closest argument/evidence I could find is an exhibit [Doc. 61-1] rounding up dozens of Google Image searches for Rastas and Jamaican jungles and ganja tours, but that was to counter Cariou’s inference that the only way to take pictures of Rastas is to do what he did, and live with them for ten years. [Which, according to his deposition, it turns out he didn’t do, But whatever.]

Wow, is it really 12:30? I’ve gotta get some sleep. OK, we’re back. And what follows is, by any measure, too long.

Continue reading “The Five Most Ridiculous Things About The Richard Prince Copyright Decision”