Last winter I was visiting museums on the Mall a lot in order to write this review/roundup. It was pretty grim going, and I don’t think I was wrong about the mood.

These black cubes appeared along my drive, and I would take note of them, think about them. They had an eye-catching, out-of-place presence and no discernible purpose, which made them feel of temporary sculpture. They were also alongside a conduit road whose main feature was not slowing you down on your way, which created a tension, if only for the briefest (passing) moment.

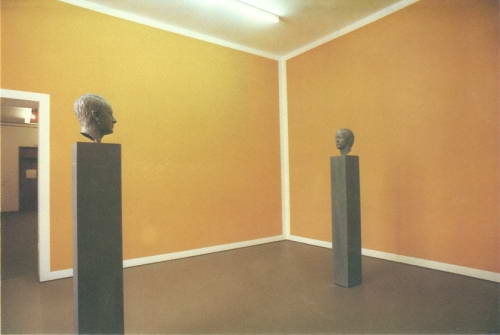

They made me think of Tony Smith’s Die, obviously, but if anything, that easy association pushed back against my own doing anything with these cubes. They also made me think, though, of Smith’s massive 1967 sculpture Smoke, which, like so much of his work, first came into being as black plywood.

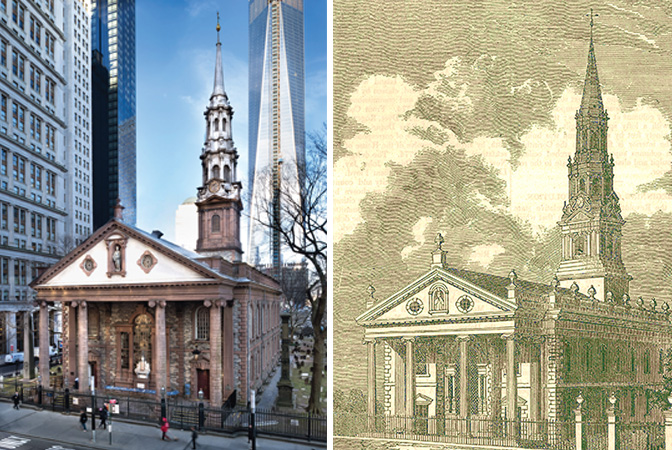

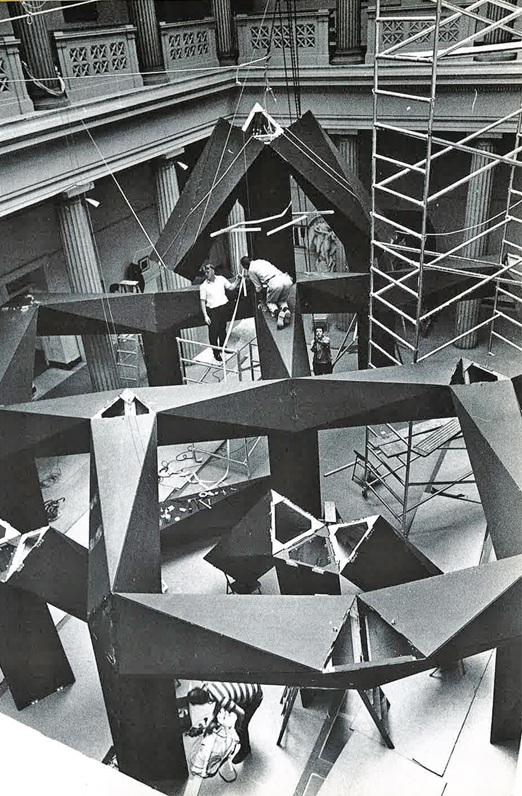

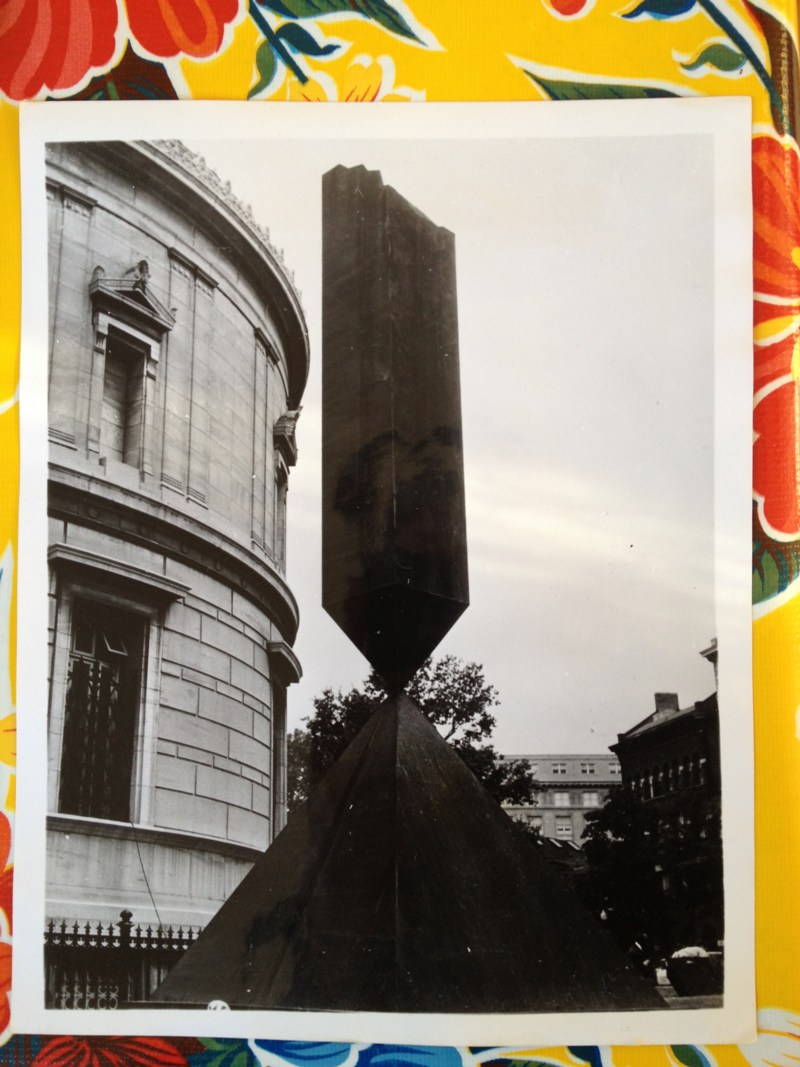

Smith built Smoke in one half of the Corcoran’s atrium while Ronald Bladen built X in the other. Or rather, the Corcoran built Smoke and X for Smith and Bladen. The sculptures were commissions, fabricated by the museum’s carpenters for a three-artist show called, “Scale as Content.” [The third work was Barnett Newman’s Broken Obelisk, which was installed outside, facing the White House and the Washington Monument. The Corcoran ended up owning none of these works.]

Artforum’s retardataire reviewer didn’t like it “as art,” but “Scale as Content” feels pretty on the nose for Smith, who realized Die in six foot steel in 1968 after noodling for six years over a six inch cardboard model. [In 1967 Smith also showed a plywood version of Maze, and published the cardboard version in Aspen Magazine.]

Anyway, these boxes were not placed where they are for artistic reasons. I finally went to investigate them on foot in January. They’re cover/markers for some infrastructure node, presumably related to the construction staging on the lawn between the Tidal Basin and the Washington Monument. They’re close to crosswalks; maybe they’re hookups for eventual pedestrian crossing signals.

But this is not really the time, and these are not in the place, for benign indifference to the apparatus of the state. In this era of plate readers, wifi sniffers, Stingrays, and ICE raids on pizza delivery guys, these black boxes now feel like–like black boxes. Given what we keep finding out on a daily basis in DC, what could we possibly not know yet? You don’t have to be Trevor Paglen to wonder about the menace of ersatz apparatuses popping up on the major thoroughfares of Washington. Are they some nefarious surveillance system in waiting, or one that’s already at work?

The intervening months have also brought Paglen’s Trinity Cube and Rachel Whiteread’s cast voids to town, and so I still pass these cubes and still think. One thing I think a lot about is the point of declaring something a work. Another thing is declaring. Another is a work. Sometimes, during a year of wondering if I’m rationalizing, I wonder if the reflexivity, the impulsion, the emptiness of these things are reasons in themselves. Emptiness as Content.

As Tony Smith said about Die: “This is a complicated piece. It has too many references to be coped with coherently.”