Let’s take a moment to consider the greatest Cady Noland sculpture of all time [No offense, Tanya!] Which I forgot about for 23 years.

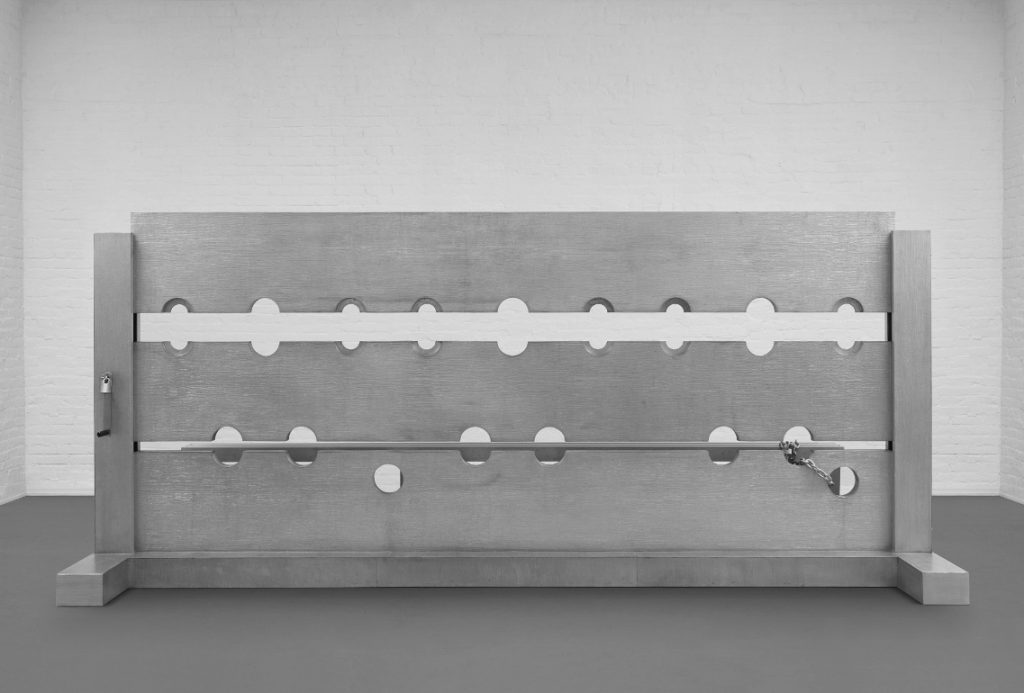

Tower of Terror (1993-94) is a 4-meter long, three-person stockade made of cast aluminum. It was created for Noland’s room-filling installation in Public Information: Desire, Disaster, Document, the show that inaugurated SFMOMA’s new building in 1995. I went to that show. And have not recalled it until seeing Tower of Terror turn up for sale at Phillips this week. But I am not alone in this blinkered state.

Gary Garrels surely knew. He helped curate the SFMOMA show. And ten years later, when he helped Harvey Shipley Miller assemble a massive collection of works on paper to be donated to MoMA by the Judith Rothschild Foundation, he made sure to get Noland’s preparatory drawings, 21 of them. [They were only digitized some time after I confessed to knowing nothing about them in late 2015.]

But he did not get the sculpture itself. Where did it go? Norah and Norman Stone apparently didn’t keep track of it. Though they were friends of SFMOMA, and the artist, and had an even bigger work by her, they called their Log Cabin Blank with Screw Eyes and Café Door (Memorial to John Caldwell) “Cady Noland’s only outdoor sculpture to date.”

Which means they did not know that Tower of Terror had been installed outdoors at Dowling College, on the south shore of Long Island, for more than 20 years. The sculpture had apparently been acquired directly from Noland in 1995 by Albert & Beverly Davidson of the Davidson Aluminum & Metal Corporation, and promptly donated to Dowling, a small college on a former Vanderbilt estate near the Long Island Sound. It apparently sat in the woods, near the student parking lot, and in front of estate’s former Ice House, which had once been the residence of the college president, but was, I believe, being used as office space. I finally found it on Google Maps. Let’s say it was not where I expected.

So for 22 years, students walking from their cars to– actually, to nowhere. As far as I can tell, the actual school buildings were in the opposite direction. So who ever passed by? Who knew that this massive masterpiece was sitting in public, just off the Southern Parkway, an hour outside the city? Someone knew, because when Dowling College went bankrupt in 2016, they knew to swoop in and liquidate that asset. And now it will be flipped.

The new owners and Phillips also know–by now, don’t we all?–to consult Ms. Noland about her work. The auction listing carries a new non-disclaimer: “We thank Cady Noland for reviewing the cataloging for this work.” We all do, Phillips, we all do. And we thank her for making it. [So if she is fine with this sentence, must we be? “Tower of Terror, 1993-1994, represents the central tenant of Cady Noland’s conceptual practice: the subversion of the American psyche through celebrity and violence. “]

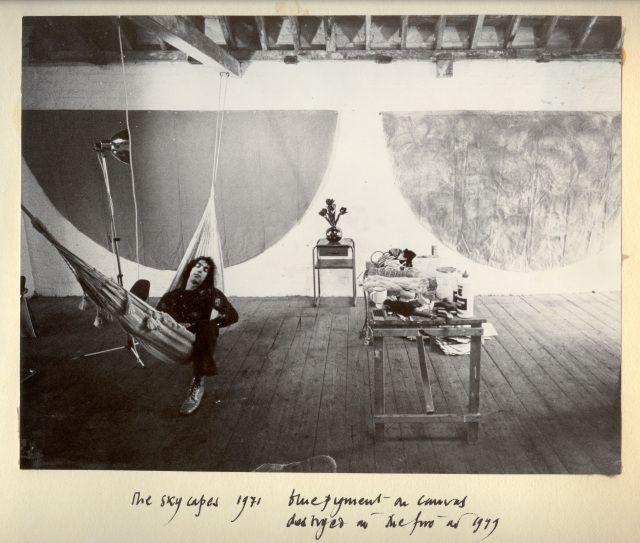

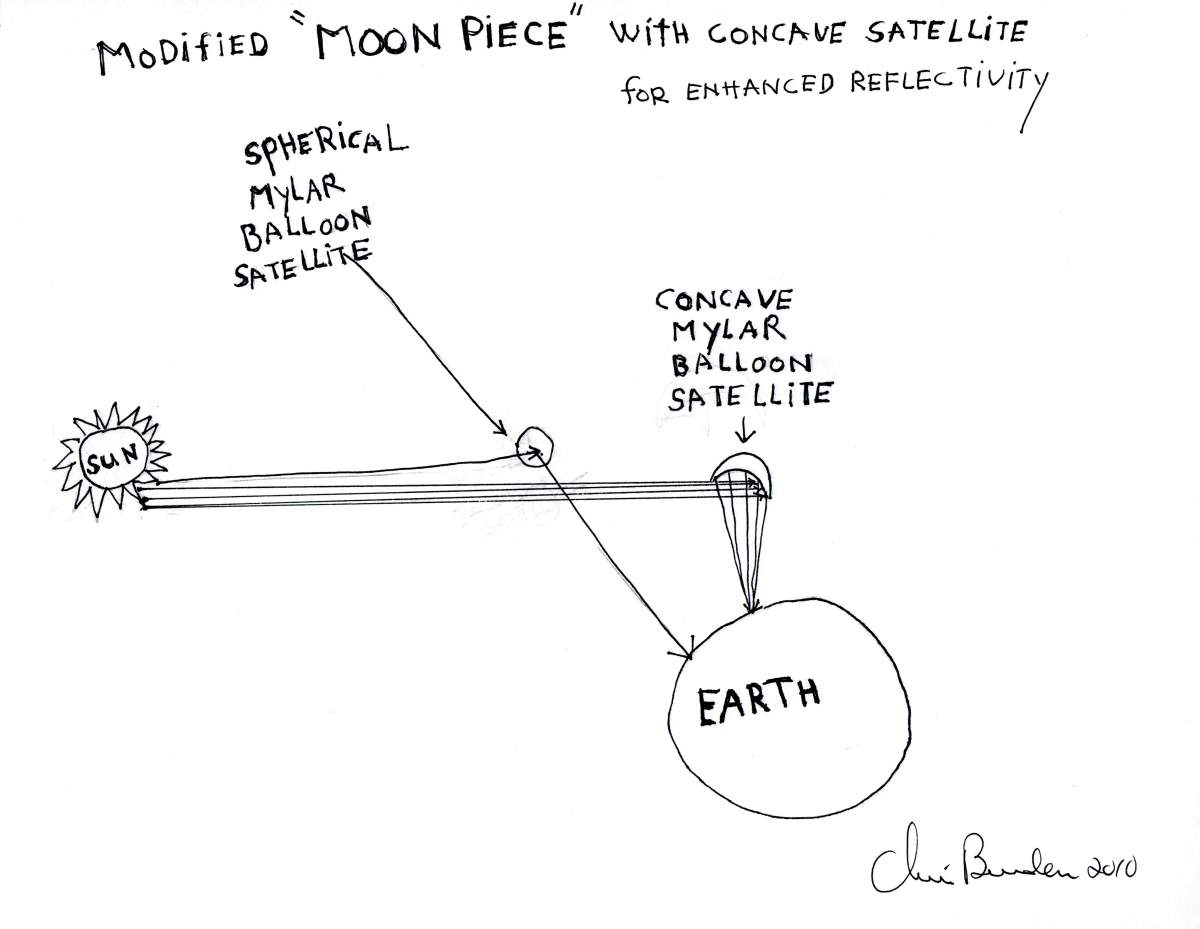

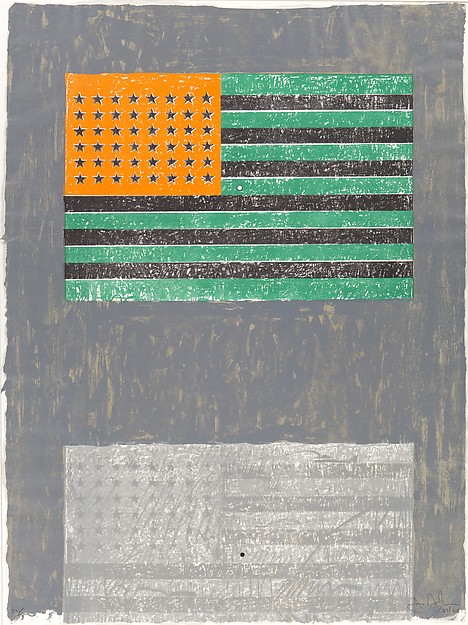

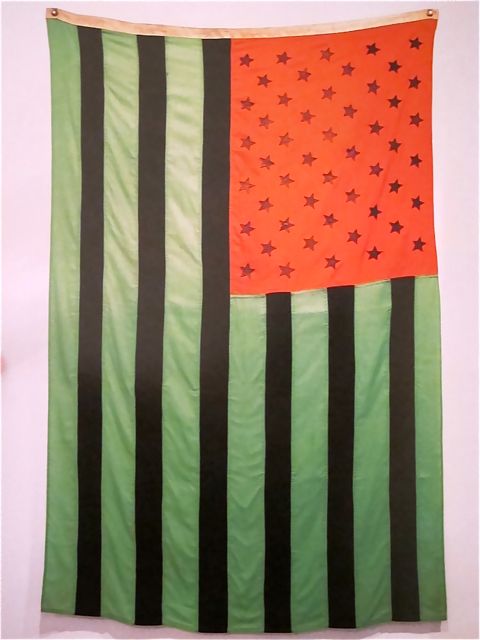

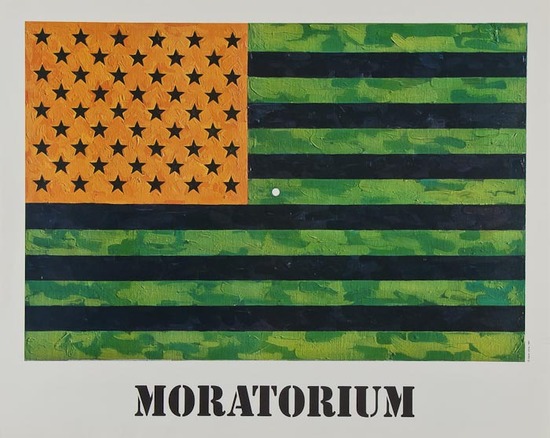

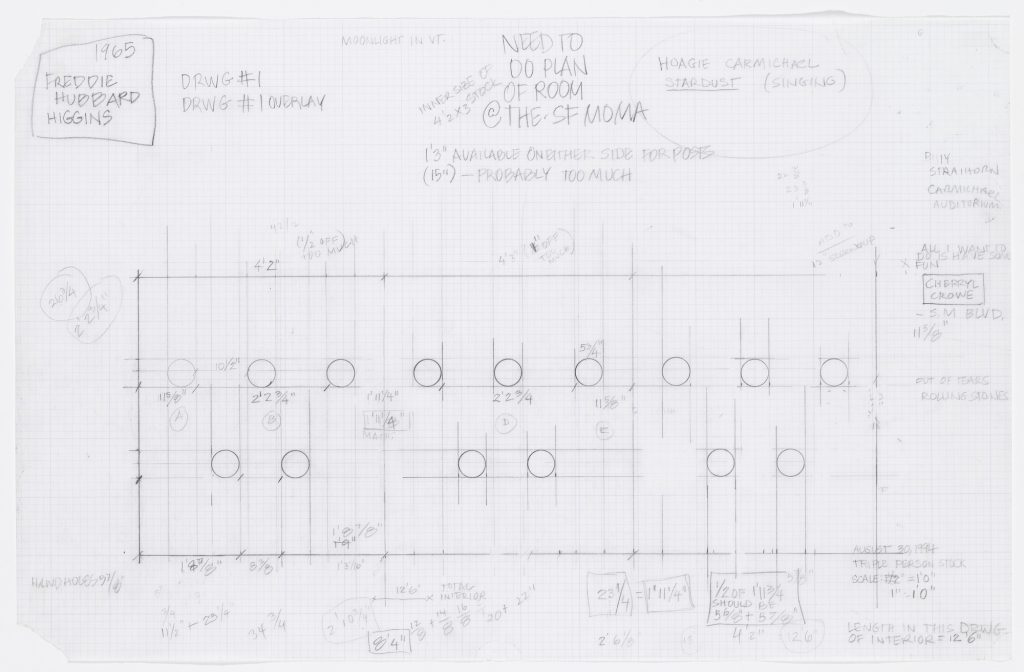

Some other thoughts about this work that I don’t really know how to fit into a narrative: Tower of Terror is also the name of a Disney ride that opened in July 1994. [The study above dates from August.]

Another stockade from the SFMOMA show was recently put up for sale, until it wasn’t. In November 2016, the Sammlung Goetz sent the domesetically scaled Beltway Terror to Christie’s with an estimate of $800,000-1,200,000. Then it was withdrawn. Beltway Terror looks very similar, yet also substantially different. Obviously and adorably, it only fits one person. But it is also stamped aluminum laminate over wood, where Tower of Terror is cast aluminum. It now seems significant that the work was acquired by the owner of an aluminum processing company. Perhaps it was acquired in exchange for fabricating it.

Perhaps it was cast from a stamped sheet-on-wood model? No. When I see the video, there is either some Gober-level simulacralization of the seams, or this is stamped aluminum laminated on cast or milled aluminum. In any case, Tower of Terror is epically superior to Beltway Terror. I hope whoever buys it puts it where it belongs, in a museum of modern art.