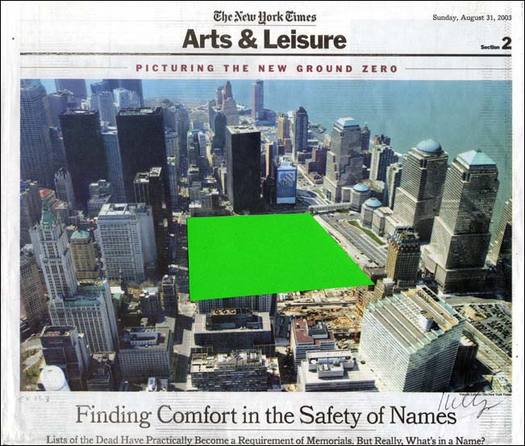

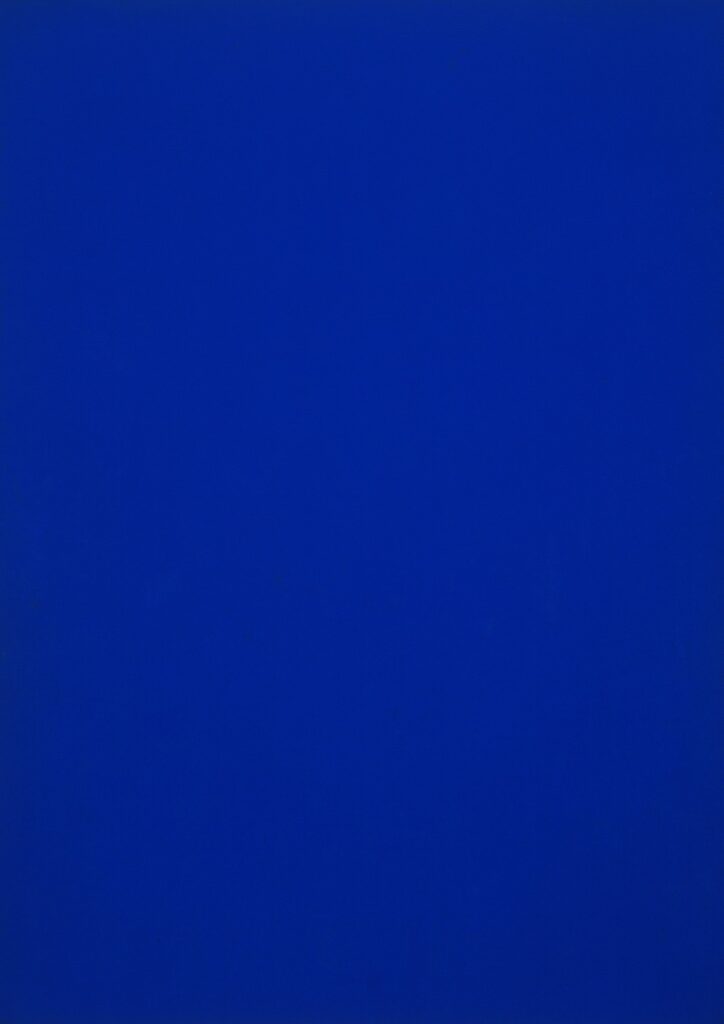

My interest in the decoupling of the artwork and ownership predates the creation of non-fungible tokens. One work conceived in 2009 is a [sic] jpg of fixed parameters, with varying physical counterparts. One ongoing series, begun in 2014, involves realizing works I own out of objects or situations over which I have no control. Rather than pursue a way to make those works saleable, I use them to consider what art can be if it is not a monetizable, speculative commodity, but perhaps a legal tool for reducing police violence, or an ingrained habit of an entire city.

In her profound essay for the Swedish art magazine Paletten, “The Ghostchain (Or taking things for what they are),” Geraldine Juárez essay looks at the same question from the opposite position. NFTs are the manifestation of assetization, where an artwork–or other object, digital or physical–is considered uniquely for its performance as a financialized asset.

Crypto-fueled hypercapitalization that recreates the divine right of kings on the blockchain is not inescapable, Juárez argues; another future is possible.

But if assets are just made up narratives about the future, perhaps we can create other stories where the value of the future is brought into the present with the intention of decapitalising these chains and make it socially and politically expensive to keep adding blocks in them, until blockchain infrastructures eventually turn into abandoned ghostchains…

Ghosts of private property.

So far, of course, the dematerialization of the art object hasn’t slowed its commodification, or at least the propensity for the art world to art market it. Juárez wrote her essay in reluctant response to David Joselit’s call [pdf] for breaking NFT’s “social contract that values property over material experience.” Joselit’s hope is for “spectatorial generosity,” that looking is enough, the October version of getting paid with exposure. Juárez sees beyond that. Just as right-clicking won’t pay the bills, it also won’t eliminate the incentives for aping. Instead, she argues for decapitalizing, eliminating the returns:

make it socially and politically expensive to keep adding blocks in them, until blockchain infrastructures eventually turn into abandoned ghostchains.

These copies could become a valuable historical document – a decentralised digital monument to the financial impulse of our present time of turning anything into an asset at any cost. A monument for a future where we no longer have time or patience for destructive technologies without social utility.

Whether we lose patience with art’s utility as a means for social exclusion, inequity, and speculation, of course, remains to be seen.

The Ghostchain (Or taking things for what they are) [paletten.net]

NFTs, or The Readymade Reversed [October, pdf]