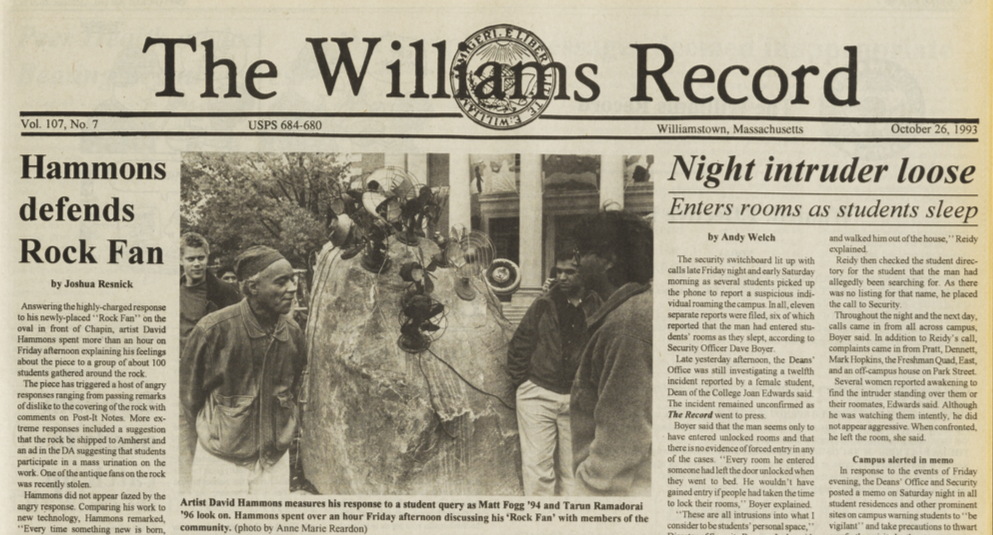

Two weeks ago on the 378th episode of Modern Art Notes Podcast, Tyler Green discussed Cy Twombly: 50 Days at Iliam, a monograph published by Yale University Press and the Philadelphia Museum, which has the 10-painting series permanently installed in its own gallery. Green’s guest was Richard Fletcher, a classics professor and one of six contributors to the book, alongside PMA curator Carlos Basualdo and Nicola Del Roscio, who heads the Cy Twombly Foundation.

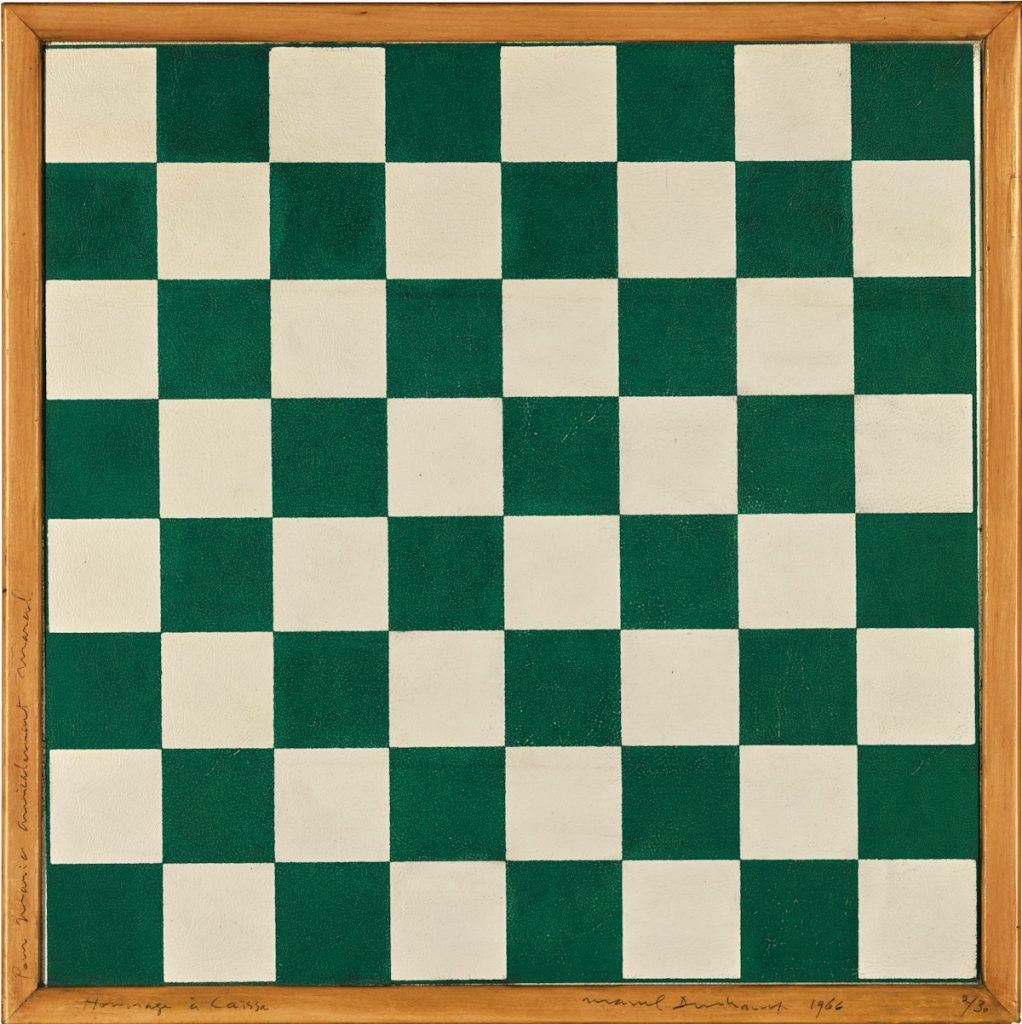

I’d anticipated an episode on Twombly, because Green had recently tweeted about the extremely small and useless images of Twombly’s paintings on the Philadelphia Museum’s website, which, word. I promptly tweeted back an unhelpful joke, by upsizing the jpeg of one of the paintings, Achaeans in Battle, into a uselessly pixelated mess [above].

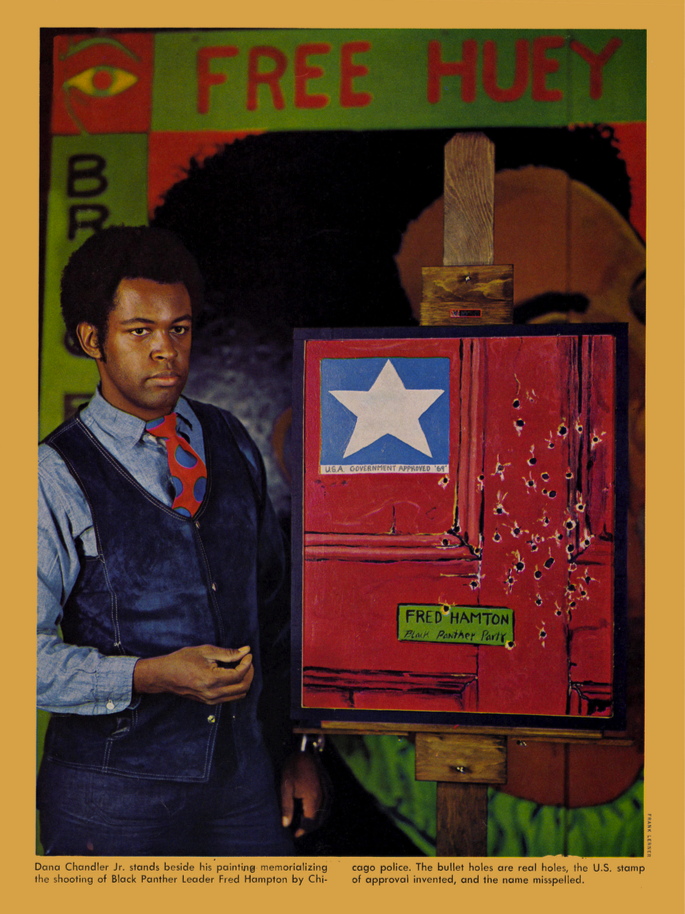

This is something that has occupied my mind and work for more than ten years, when I first turned a tiny jpeg of a Richard Prince Cowboy photo into my own work as a critique of MoMA/Gagosian/Prince’s refusal to provide images for an exhibition review at Slate. A related concept was articulated a little later by Hito Steyerl as the “poor image,” a low-res image optimized for networked circulation by being stripped of information. A crappy, digital simulacrum of an original [sic], complete [sic], physical and visual experience with an artwork.

Not knowing about the Iliam book, I assumed Tyler was going to be talking to Joshua Rivkin, who has a new biography of Twombly called Chalk: The Art and Erasure of Cy Twombly, which I’d recently finished. Rivkin’s book is a labor of love and pilgrimage; inspired by his regular presence in front of Twomblys at the Menil as a teacher and guide, the book documents his attempts to gain insights into Twombly’s life and work from the places he lived and worked: Rome, Gaeta, and Lexington. What Rivkin finds is the thwarting presence of Del Roscio, who disapproves of the biography project, silences sources, and denies Rivkin access to Twombly’s archive, as well as use of his images.

But no, it was Iliam. Green talked with Fletcher about details of Twombly’s marks and texts; his use of a Greek delta instead of an A to write Achilles and the Achaeans; the symbological vocabulary of the series’ colors; what’s going on with all those phalluses; and Twombly’s relationship to his literary source, Alexander Pope’s translation of the Iliad. [Fletcher also discussed a discovery he’d made, of a different source for some of Twombly’s texts. It’s hot, academic stuff.]

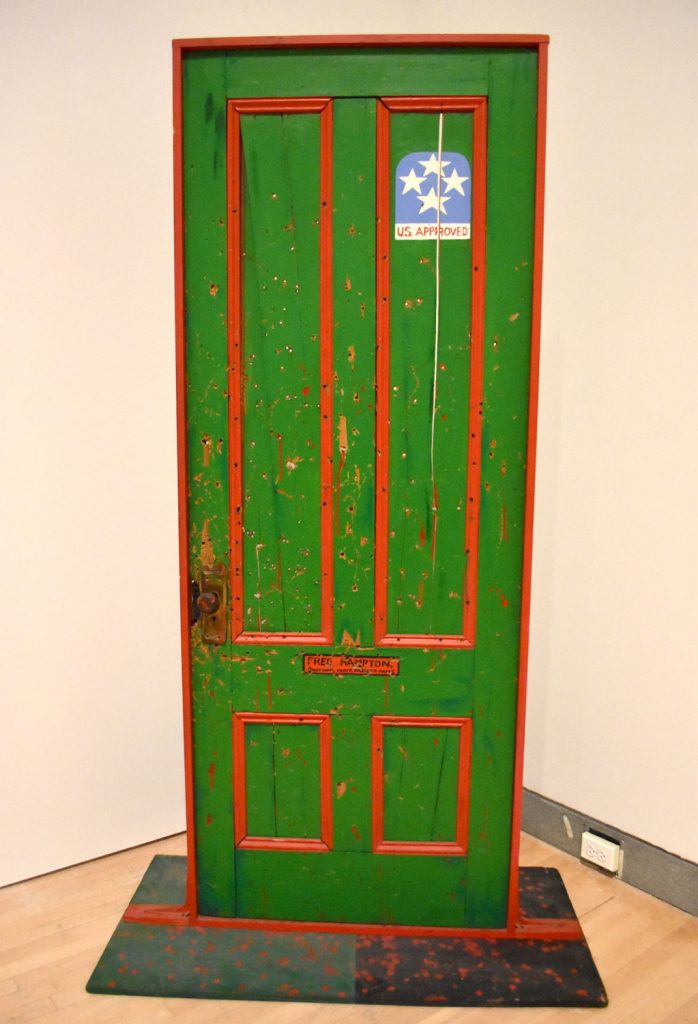

I mention all this scholarly and critical detail because of the sheer bafflement at learning, a few days after the episode was released, that the Twombly Foundation had sent Green a cease & desist letter demanding that images of the Iliam paintings be removed from the MAN Podcast webpage. Those would be the images of the 50 Days at Iliam works whose details were being studied and discussed. By an author of the book. Published by the museum and Yale. It’s an extremely impoverished attempt to exert control over consideration and discussion of Twombly’s work by an extremely interested party, using an extremely wealthy foundation. That it is being done in the name of one of the most important and formative artists in my own life is extremely disappointing.

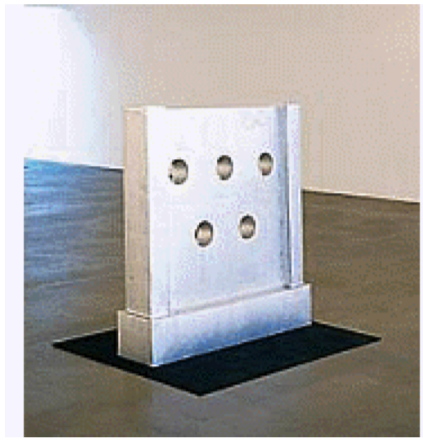

As soon as I saw Green’s tweet about the C&D, and his removal of the Iliam images, I looked for it on Internet Archive. No luck. But I ripped a screenshot of the page from Google’s cache. In a couple of days, it had been replaced by the stripped down version. So except for anything Green might have archived himself, I think this screenshot is the only record of the original page. I printed it as Untitled (Foundation), an artist book in an edition of 10. The widest printer I could find was 36 inches, so it came out 3 inches wide and barely legible. The images are smaller than even the Philadelphia Museum’s website.

I am sending this artwork to people who appreciate the importance of fair use to progress of Science and the useful Arts; to the freedom of the press and expression; to the transformational creation of new art; and to the accountability to the public good that is expected of tax-exempt foundations and those who control and benefit from them.

Continue reading “Cy Twombly Rip”